Bay of Plenty and Central Plateau

community visit 2024

What we heard from those in the Bay of Plenty and Central Plateau community, helps us understand how services are working to improve outcomes for and , and their .

Before we visit a community, we request data from Oranga Tamariki and NZ Police to help with our planning. This data provides the context for our visit and highlights areas we may need to look at to understand what is working well or what might need to change.

You’ll see some of this data in the key themes in this share back, and in the A3 summary for Bay of Plenty and Central Plateau.

As with all our reports, data is one part of the overall picture for your community. The voices of , , and , and those like you who support them, are at the centre of our .

Who we heard from during our visit to Bay of Plenty and Central Plateau

| 71 | tamariki and rangatahi |

| 28 | whānau |

| 36 | caregivers, both whānau and non-whānau |

| 47 | representatives from Māori/ organisations and Oranga Tamariki strategic partners |

| 62 | Oranga Tamariki kaimahi |

| 9 | Open Home Foundation kaimahi |

| 19 | Police kaimahi |

| 27 | other government agency kaimahi |

| 23 | non-government organisation kaimahi |

| 48 | group home and residence kaimahi |

Information about how we analyse what we heard can be found on our website: aroturuki.govt.nz/what-we-do

Community contracts and funding

- Consultation with local Oranga Tamariki sites

- Mentors are important to , but there is not enough contracted funding to meet this need

Staffing and funding changes at Oranga Tamariki

- The Oranga Tamariki restructure, resource cuts, and what local staff perceive to be a hiring freeze, have led to increased frontline caseloads and place and rangatahi at further risk

- Oranga Tamariki kaimahi who hold high caseloads do not have time to conduct social worker visits or communicate with tamariki, rangatahi and

- We heard Oranga Tamariki national office is not consulting with local sites about site budgets, resulting in insufficient funding to keep Tamariki and rangatahi safe or support whānau and caregivers

- Increased thresholds for reports of concern and poor communication are creating uncertainty about the safety of tamariki and rangatahi and whether support has been provided

- Te Pūkāea is working well to triage reports of concern in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, however there are some misunderstandings on how they are supported to make assessment decisions

- There is concern that a lack of care options is putting tamariki and rangatahi at risk of further harm

- Placement referrals lack information about tamariki and rangatahi needs, which may increase the risk that placements are unsuitable and break down

- A lack of respite care options is risking caregiver burnout

Referrals and information sharing

- Incomplete referrals from Oranga Tamariki impacts the support organisations can provide to rangatahi and their whānau

- Transition to adulthood services feel transition support is not prioritised by Oranga Tamariki due to a lack of communication and awareness of the services they provide

Support to participate in education

- We heard rigid thresholds to access support is resulting in tamariki and rangatahi not participating in education

- Many rangatahi are better supported in Alternative Education and employment pathways than in mainstream education, but there are limited services available and barriers to their accessibility

- Reliable, safe and cost-effective transport is already a barrier to school attendance, with the impact of planned funding cuts by the Ministry of Education causing concern

- Schools are trying to find creative ways to meet the wellbeing, behavioural and disability needs of tamariki and rangatahi

- Safety Planning at School

- Funding to convene family group conferences appears limited and inconsistent, which is a barrier to holding culturally appropriate that support tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau

- Limited availability and funding of community services are barriers to delivering the support identified in family group conference plans

- Many community providers feel they must take on the responsibility of Oranga Tamariki to ensure tamariki, rangatahi and whānau understand the FGC process and have their voices heard

Working with rangatahi who offend

- Police say they make considered decisions to apprehend rangatahi and assess the need to use force, but some rangatahi feel they were unfairly treated by police

- Police officers try hard to explain rights, however some rangatahi still do not understand what their rights mean

- A practice shift in Police to a holistic and preventative approach, including Te Pae Oranga process, is working well to provide wraparound support to rangatahi and reduce reoffending

- Police rotation policy affects relationship building and creates inconsistency

- Some organisations are working hard to embed in their practice to support the cultural needs of tamariki, rangatahi and whānau Māori

Consultation with local Oranga Tamariki sites

We heard that local Oranga Tamariki sites were not consulted in the review of Oranga Tamariki community contracts. Kaimahi from multiple organisations, including Oranga Tamariki, believe this has resulted in contracts that are not fit for purpose, including funding to community agencies to deliver services that do not match the needs of , and .

“We’re encouraged to lean on the community, but all our community [providers] have had multiple contracts taken. We need them [community providers] but the powers that be decided nah.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

“We no longer have a list of providers in Tauranga who have had their contract renewed. We’re making referrals and hoping for the best. [Local supported bail providers] now have a 12- week wait list and its likely to increase. In the email it said its because OT [Oranga Tamariki] cut our contracts. We lean on them [provider] and they have done a fabulous job for whānau and working with kids with high and complex needs.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

“Our kids are hearing on the news about funding cuts and have mentioned running away so they won’t be kicked out of here. How do you manage those conversations when they are worried about the place closing?” – Kaupapa Māori organisation kaimahi

“The youth are not getting their needs met in a timely manner, which is a care standard! For example, requesting for therapy options and those being declined, or sensory items for neurodivergent kids and those getting declined. We are just questioned constantly, and it all came back to funding - almost feels like we are begging for it to meet the tamariki and rangatahi needs above and beyond what our contract is.” – Group home kaimahi

Many community organisations told us that due to cuts in their contracts they are having to be “creative” to fund their work, with some organisations working without funding, some above and beyond their funding, and others facing cuts and scaling back their services. They spoke about the “sizeable” impact of continued contract uncertainty, with some still unclear on proposed changes and timeframes and working without funding months into the 2024/25 financial year.

“Oranga Tamariki are funding about 30 percent of the work that we do – we’re actually using our [Ministry of Social Development] crisis funding for adults to do [the sex health program]. We recently have been doing some work for Oranga Tamariki with kids who have problematic sexual behaviour, but that’s not funded by Oranga Tamariki. We know that those who have experienced sexual abuse have higher rate of causing sexual harm.” – NGO kaimahi

“Our contract and funding expired on 30 June 2024. We have been currently running for two months without funding … We are told ‘yes’ to more funding but not when, so we have no timeframe. We have no one to contact at Oranga Tamariki anymore ... We are not a provider who had pūtea [money] to tie us over ... We contact them [Oranga Tamariki] every other day and there is no new information. The government tell us to fill the beds but haven’t given us funding.” – kaupapa Māori organisation kaimahi

The contract changes are also impacting on local relationships, with some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi telling us about the negative impact on their relationships with social service providers.

“I don’t feel tika or pono at the moment. We’ve worked closely with iwi and forged good relationships, it’s been hard, but the goal-post changes then we have to go back and tell them. It breaks trust … it’s the difficulties in contracts that’s the issue and their trust in us is dwindling, yet we are asking for more and more with less [funding].” – Oranga Tamariki leader

We also heard there is a lack of parenting courses in the area to support whānau to care for their tamariki. The existing courses have high thresholds to join, which many parents do not meet. Services often run based on set schedules and will not run if there not enough people referred to the service, which prevents whānau from accessing services when they need it or from continuing to get support if they temporarily stop attending.

Mentors are important to rangatahi, but there is not enough contracted funding to meet this need

Rangatahi, whānau, Oranga Tamariki, Police, and community agencies all spoke about the positive impact of mentors. However, cuts to funding and contracts are reducing the capacity and availability of mentors. In Rotorua, we heard two community agencies provide mentoring services along with supported bail programmes, and more rangatahi need mentoring than they have space for. In Tauranga we heard there are no longer any supported bail or mentoring programmes available for Oranga Tamariki to refer to. Blue Light runs mentoring for rangatahi under alternative action plans or less serious youth justice interventions, but they cannot accept referrals from Oranga Tamariki as their contract was cut.

The change to contracts and funding for mentoring services has resulted in mentors working triple their hours without extra funding as “favours” to the local Oranga Tamariki office, rather than leave rangatahi without support and in breach of court ordered mentoring hours. Other mentoring services who do not have Oranga Tamariki contracts are also providing unfunded mentoring at the request of Oranga Tamariki kaimahi while “struggling to stay afloat”. The strain on these services has impacted on the regularity and quality of support they can offer rangatahi to help them make long term positive change and not re-offend.

“It feels like quantity over quality and not very preventative over the amount of time, it’s too short term … it’s not enough for the rangatahi, or for the whānau as well, to make their transformative change.” – Iwi social service provider kaimahi

Rangatahi and whānau shared how important mentors were, and the difference mentors make in rangatahi lives. We also heard about the significant role mentors play in family group conference and court plans.

Rangatahi told us mentors from organisations like Maatua Whāngai and Te Waiariki Purea Trust supported them to complete their community hours and helped them find forklift driving courses or other trades. Mentors take them places, support them with developing life skills, and encourage them to try fun new experiences.

“He does stuff for me. Before I was out of here, I was on a bracelet [in the community]. I couldn’t go places at any times. He handles that so I can; he come and picks me up, so I wasn’t home all the time. The police would come over and they’d say ‘you’ve breached your conditions’, [so I would] give them my mentors number and he would tell them what I was up to.” – Rangatahi

“[Mentors] give us food, proper food. I will be there maybe three or four days a week, on Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. They help me with life skills. They take me out for kayaking, swimming, doing cool stuff.” – Rangatahi

Rangatahi who were in Te Maioha o Parekarangi appreciated when their mentors visited them in person or checked in over the phone because it gave them another person to talk to, someone who understood them and worked with them at their pace. Mentors also helped rangatahi understand some of the processes that were happening to them.

The Oranga Tamariki restructure, resource cuts, and what local staff perceive to be a hiring freeze, have led to increased frontline caseloads and place and at further risk

Many Oranga Tamariki sites said they are understaffed with overworked kaimahi holding high caseloads, and many cases are unallocated, putting the safety of tamariki and rangatahi at risk.

“We only want to keep kids safe, but the ministry and government are making decisions that appear to create more risk for tamariki and staff.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

“Our social workers could have up to 50 [alternative intakes] with the view of those coming down over time but with the idea that [positions] are not getting replaced. Social workers feel like, ‘why should I go hard on this if it’s not going to be valued?’” – Oranga Tamariki site leader

We heard the Oranga Tamariki restructure has impacted the frontline by cutting staff and resources, moving kaimahi between teams, and putting a freeze on new hires. Both care and protection and youth justice Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us they must choose which cases get worked on and which get “left behind”.

“… If they [Oranga Tamariki] had made some of these [restructuring] decisions to keep them [tamariki and rangatahi] safer, we could work with that. I know there’s going to be preventable deaths. What annoys me is that social workers will be pinpointed and their supervisors, I can accept when there’s mistakes and poor practice, but [in] the review of the next baby’s death they won’t be looking at the restructure.” - Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

An NGO kaimahi told us feel pressured to pick up the work when Oranga Tamariki social workers do not deliver youth justice plans. However, as outlined in the section on contracts, these NGOs are not funded for the many extra hours of work they pick up.

“It’s the norm that we are going to have to deliver the plan [because] I know the YJ [Youth Justice] workers have so many cases. There needs to be more YJ [Youth Justice] social workers.” – NGO kaimahi

We heard when Oranga Tamariki kaimahi are spread across too many cases, they are having to take shortcuts, including not following organisational policies which are designed to ensure tamariki and rangatahi are safe. This includes not being able to regularly visit tamariki and rangatahi who have returned home to live with their parent/s. In 2023, our in-depth review Returning Home From Care highlighted the need to visit and support tamariki and their parents during this time. The latest report from Oranga Tamariki on the safety of children in care also highlights the risk of harm.

“We’ve got young people returned to [parents]. For me, I touch back once, sometimes a phone call. It’s never that great from our side. The work just doesn’t stop.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

Community organisations also spoke about the loss of liaison roles at Oranga Tamariki. No longer having a single point of contact within Oranga Tamariki has impacted on their relationships and communication with local sites.

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi who hold high caseloads do not have time to conduct social worker visits or communicate with tamariki, rangatahi and whānau

Many whānau are frustrated by a lack of communication from Oranga Tamariki social workers, which can delay plans, leave them uninformed, and make them feel like only community organisations support them. For example, a whānau member told us communication is a “one-way street” as Oranga Tamariki is only responsive if they want information.

“Oranga Tamariki were meant to visit every six weeks but hasn’t since June … [The] only people who are regularly coming through are [kaupapa Māori organisation].” – Whānau

Oranga Tamariki and community kaimahi told us high caseloads prevent Oranga Tamariki social workers from visiting tamariki and rangatahi regularly or forming meaningful relationships with tamariki, rangatahi and whānau. Some Oranga Tamariki social workers ask NGO kaimahi to visit tamariki and rangatahi on their behalf.

“Two of our rangatahi as a result of a report of concern came into the [centre]. In two weeks, they haven’t heard back from their social worker. These kids are left waiting.” – NGO kaimahi

“We have been working with the whānau for two years because [Oranga Tamariki] put plans in place a while back and didn’t follow up to see if their plans were working. So, we knew that the family violence kept happening.” – NGO kaimahi

We heard Oranga Tamariki national office is not consulting with local sites about site budgets, resulting in insufficient funding to keep tamariki and rangatahi safe or support whānau and caregivers

Oranga Tamariki site leaders and NGOs told us Oranga Tamariki national office has been making decisions about site budgets without local consultation. Specifically, we heard national office has been re-allocating local funding to national projects without consulting sites on their local needs.

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi said this means they cannot fund the same support to whānau as they did in previous years, which one site leader said has led to an increased number of complaints made by whānau to sites. Community and Oranga Tamariki kaimahi are concerned the funding changes will put tamariki and rangatahi in care at higher risk of abuse.

“Kids become numbers, and I know what it’s like to be a number, but I was lucky to get good parents compared to others when I was in the system … we still have kids abused in care when they are supposed to be protected.” – NGO kaimahi

We heard that funding has been cut to the caregiver allowance and the Permanent Caregiver Support Service (PCSS), which has made it difficult for social workers to provide caregivers with support, such as getting financial approval for permanency plans. Some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi highlighted inconsistencies in the financial support available to caregivers, both across and within the region.

“With the foster care allowance [Oranga Tamariki caregiver allowance] – [cost of living] prices are increasing and I’m driving 250 kilometers a week for appointments and the hours sitting in traffic. All of a sudden Oranga Tamariki said we’re going to drop it now ... Two months ago, they said if you want to have a conversation about the foster care allowance dropping, you can email the supervisor. I didn’t hear from him [Oranga Tamariki supervisor] for a month and then he said sorry I’ve been on leave, that’s the ministry decision.” – Oranga Tamariki caregiver

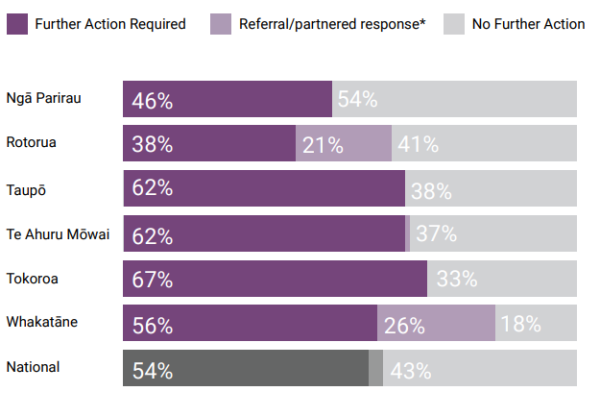

Data from Oranga Tamariki shows a large variation between Oranga Tamariki sites in how reports of concern are responded to, particularly the proportion that result in no further action from Oranga Tamariki.

The Whakatāne site had the lowest proportion of reports of concern resulting in no further action (18%) and Ngā Parirau had the highest (54%). Whakatāne also had the highest proportion of reports of concern referred for a partnered response (26%).

In the eastern Bay of Plenty region (which includes the Whakatāne site), Te Pūkāea helps triage reports of concern and supports and who do not meet the statutory threshold to require Oranga Tamariki intervention.

Local response to report of concern

Some sites record decisions to refer or provide a partnered response to a report of concern as ‘referral and partnered response’, and some record it as ‘no further action required’.

Increased thresholds for reports of concern and poor communication are creating uncertainty about the safety of tamariki and rangatahi and whether support has been provided

We heard from kaimahi at a few government agencies that Oranga Tamariki takes too long to process reports of concern and that they need to submit multiple reports of concern before action is taken. Likewise, some kaimahi do not hear back about reports of concern they have submitted, leaving them uncertain about whether the child is safe and if support has been put in place for tamariki and rangatahi.

Some Oranga Tamariki site leaders told us there have been significant delays in reports of concern being sent to sites from the National Contact Centre, with “over 100 pieces of work [reports of concern] that were over 22 days old”. A lack of capacity and high workloads are further exacerbating the delays and resulting in an “unintended flow on to social workers” to appropriately respond to and handle reports of concern.

“Their [the Oranga Tamariki] threshold seems to be climbing because of their inability to stay on top of things. I know that they can’t handle it all because of the amount of ROCs [Reports of Concern] that are coming through. When people fill that ROC, the expectation is that [Oranga Tamariki] will do something about it sooner rather than later.” – police officer

A couple of Police kaimahi and some NGO kaimahi felt the threshold for response from Oranga Tamariki has increased, especially in cases relating to family harm. This was a particular concern for police kaimahi who feel there is less of a prevention focus. Some professionals expressed concern about the lack of action and much-needed support not being provided to tamariki, rangatahi and involved in family harm.

“Exposure to family harm isn’t generally enough [for Oranga Tamariki to take action], family harm doesn’t meet the threshold. These kids are going to grow up, they would be saying ‘you were at my house every week and you didn’t do anything’, only because they didn’t meet the threshold.” – police officer

Oranga Tamariki site leaders told us they sometimes receive reports of concern from health professionals that do not meet the statutory threshold, or that they feel are best addressed by mental health professionals. Oranga Tamariki social workers expressed feeling as though these cases are handed over to them by default, and that poor communication and a lack of support from Health is creating further barriers to addressing mental health needs of tamariki, rangatahi and whānau. Likewise, one Health kaimahi agreed that health professionals are not always aware of the threshold for Oranga Tamariki responding to a report of concern or the quality of information that needs to be included in concerns raised.

“Sometimes they know we have the power, if tamariki/ rangatahi with mental health that is out the gate, they know we can uplift the children. We get that side, but we are not mental health professionals.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

This works both ways, and sometimes professionals do not report concerns when they should. This lack of awareness echoes what we heard in our report Towards a stronger safety net to prevent abuse of children, in that agencies do not always understand when and how to raise concerns with Oranga Tamariki. Dame Karen Poutasi’s review recommended that education and training across agencies could improve understanding about when to make a report of concern. However, when reports of concern are made, local Oranga Tamariki kaimahi need to be able to check on tamariki and rangatahi and ensure they are safe. As we heard, workload and staffing shortages are getting in the way.

Te Pūkāea is working well to triage reports of concern in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, however there are some misunderstandings on how they are supported to make assessment decisions

Te Pūkāea o te Waiora is an Alliance contract led by Te Tohu o Te Ora o Ngāti Awa. They triage calls re-directed from the National Contact Centre and help whānau to access community information and services. We heard Te Pūkāea o te Waiora is working well to triage reports of concern and support tamariki, rangatahi and their whānau in the Eastern Bay of Plenty (Whakatāne). A couple of agencies spoke positively about Te Pūkāea, noting that reports of concern are responded to quickly and tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau can access a range of services in the community to support their needs.

All reports of concern that come through Te Pūkāea are either referred to Oranga Tamariki or allocated to whānau navigators, who can refer to other providers. This allows tamariki, rangatahi and whānau, who meet a lower threshold, to access support and have their needs addressed holistically.

Data from Oranga Tamariki shows that the Whakatāne Oranga Tamariki site has a greater proportion of reports of concern that result in a referral/partnered response (25 percent), compared to nationally (3 percent) and crucially has the lowest proportion of reports of concern where no further action is taken in the region, at only 18 percent. This is significantly lower than the national average of 42 percent, though some sites record decisions to refer or provide a partnered response to a report of concern as ‘no further action’. A local Oranga Tamariki leader told us that Te Pūkāea has been working well to triage reports of concern from ICAMHS (Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service) that do not meet the statutory threshold, and an understanding has developed that “Oranga Tamariki don’t need to be the ones to do something first”.

“Some of the cases we were getting in the past, were not meeting our [Oranga Tamariki] threshold. It was just really ‘need for services’ and we were annoying whānau - thinking we [were] gonna remove [tamariki and rangatahi from] whānau. By going to Te Pūkāea, they can identify if they [tamariki and rangatahi] need care and protection or not.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

“[Whānau] prefer Te Pūkāea showing up than Oranga Tamariki because we’re really quite transparent … They prefer that we’re working with them than Oranga Tamariki. They’re more open to looking at the services because they have a choice.” – Te Pūkāea kaimahi

“One of the things that we’re committed to is no case gets closed. There will be a visit. Every referral that we get through Te Pūkāea, there will be a home visit to discuss what the concerns are and offer assistance. They can decline the service, but part of our assessment is, if there are risks still existing, we can go back into [Oranga Tamariki] and escalate it back to [Oranga Tamariki].” – Te Pūkāea kaimahi

“Its [Te Pūkāea] establishment was in March this year, but it seems to be working well as a model already.” – Education kaimahi

However, some Health kaimahi were concerned about how referral decisions were made at Te Pūkāea, and the level of risk being held. For instance, one Health kaimahi said they sometimes felt “the severity of the risk was higher than what was decided by Te Pūkāea”, particularly in cases where multiple reports of concern have been made and they were concerned about the safety of tamariki and rangatahi and whether support for whānau had been put in place.

Some Health kaimahi were also concerned about the oversight of assessment decisions, with some unaware of how staff at the Te Pūkāea call centre were supported by Oranga Tamariki. Additionally, some Health professionals said they do not always hear back about the result of a referral to a service through Te Pūkāea, or struggled to get up-to-date information about tamariki, rangatahi or whānau because they are not included in the Memorandum of Understanding that would allow sharing of this information.

When we spoke to Te Pūkāea and Whakatāne Oranga Tamariki kaimahi, we were told that many of the policies and procedures at Te Pūkāea, including how reports of concern are triaged, are based on Oranga Tamariki policies and their decision response tool. In addition, two Oranga Tamariki supervisors are seconded to Te Pūkāea; one is responsible for overseeing the call centre and decisions on what happens with reports of concern, and another oversees the whānau navigators and their practice. Reports of concern that come through Te Pūkāea are uploaded into CYRAS (Oranga Tamariki case recording system) by the seconded Oranga Tamariki staff and sent to the Whakatāne site. The co-location of Te Pūkāea and Oranga Tamariki Whakatāne in the same office space enables collaboration and oversight, as Oranga Tamariki kaimahi understand how the call centre works and can directly communicate and address concerns or issues when needed.

“A lot of our policies mirror what’s in the [Oranga Tamariki] practice centre. Also, having our supervisors here, who are provided from [Oranga Tamariki], to provide the supervision, to provide the training and ensure that the inductions done. Part of our assurances that we’re going through with Oranga Tamariki is around the risk.” – Te Pūkāea kaimahi

“We use the decision response tool that Oranga Tamariki use and its great – we can respond immediately and refer to services like NASH [Ngāti Awa Social and Health Services] and the navigators. We don’t have a time limit on the calls, it takes as long as it needs to get the information.” – Te Pūkāea kaimahi

There is concern that a lack of care options is putting and at risk of further harm

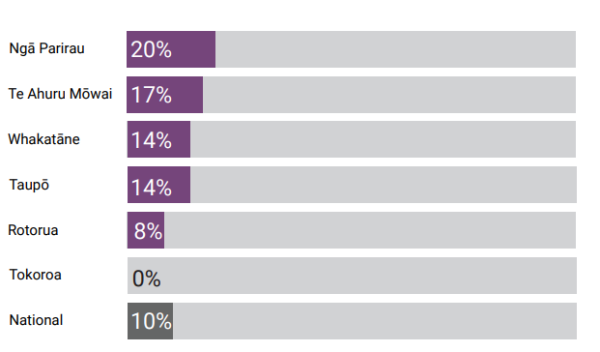

We heard a lack of care options across the region can result in tamariki and rangatahi being placed somewhere that is not well suited to them or is very short-term, such as short-term care provided by a community care partner (sometimes called bednights). Data from Oranga Tamariki shows most Oranga Tamariki sites in the region have a higher proportion than the national average of tamariki and rangatahi staying in bednight accommodation.

Proportion of tamariki and rangatahi in care and protection staying in bednight accommodation, by Oranga Tamariki site

The lack of care options for tamariki and rangatahi across the region, is worse for those with high and complex needs. This is unchanged from our last monitoring visit. Oranga Tamariki site leaders said they need to “battle for ages” to find the right care for tamariki or rangatahi with high needs. When there are no options available, tamariki and rangatahi stay in motels with resource workers, who are untrained to care for them.

We heard this lack of options is further exacerbated by a shortage of resources or training to support caregivers, and non-whānau to take tamariki and rangatahi with mental health or disability support needs.

Kaimahi from a couple government agencies told us they worry about the safety of tamariki and rangatahi when the availability of care options drives decisions, including whether to leave them in situations that pose a risk to their ongoing safety and wellbeing.

“We’re starting to ask whānau who we would not have asked to take in tamariki and rangatahi some time ago, because that is who we remove them from – but they’re the only ones that are willing to take these kids back.” – Oranga Tamariki site leader

“We found two babies sleeping under a bush at the park [with their whānau]. We thought, this doesn’t seem right. We called Oranga Tamariki. Their response was, ’we haven’t got anywhere to put them’ ... They were there in winter … our initial response was to provide them with blanket but, are we living in a world like that now?” – Police kaimahi

Placement referrals lack information about tamariki and rangatahi needs, which may increase the risk that placements are unsuitable and break down

Many community organisations told us Oranga Tamariki does not include information in their placement referrals about the needs of tamariki and rangatahi, including who they can live with or their plan. When caregivers do not have this information, they do not know if their house is appropriate for tamariki and rangatahi or if they have the training to care for them. This can cause placements to break down.

Some community provider run group homes delay taking tamariki and rangatahi while they ask Oranga Tamariki for more information. Sometimes the information has not been gathered by Oranga Tamariki or the home cannot contact the social worker to find out. We heard that not getting timely information is a barrier to supporting tamariki and rangatahi.

“Sometimes we get All About Me plans, but there’s nothing in it. We need to know what are the risks, what is the plan, but it just doesn’t have any information. So, I have to create an assessment template to see if they are accepted or not.” – social service provider kaimahi

Some (community run) group home and (Oranga Tamariki run) family home kaimahi felt Oranga Tamariki local and national leadership do not consult them or other professionals when deciding where to place or transfer tamariki and rangatahi. Aware of the lack of placements, group homes feel pressured to accept tamariki and rangatahi if they have beds available as they risk losing their funding if they “don’t get a full house”. However, given the mix of tamariki and rangatahi they already have, or the purpose of the home, some tamariki and rangatahi could be worse off if placed in a group home that does not meet their needs.

Kaimahi from group and family homes were concerned these pressured placements could put the newly referred tamariki or rangatahi at risk, or the new tamariki or rangatahi may have unsafe and harmful behaviours that put tamariki and rangatahi already living in the house at risk. For example, we heard a child in crisis was placed in a home, but the caregivers were not given any information about their needs and how to best support them. The lack of appropriate wellbeing support meant the child “escalated” and ended up in hospital.

“[Group and family] home caregivers are expected to take boys not in their area of expertise. The boys were difficult to match with other boys, due to sexualised behaviour and aggression. It was a trying time, because they were the wrong match and events happened.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

“If you [family home] have a space in a shared living situation, you [disabled rangatahi] just have to go there … even if they are unable to cope in that environment. There are no alternatives for them.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

A couple of kaimahi from community run group homes also told us that decisions to remove tamariki or rangatahi from their care can be made without their input or knowledge. We heard of one example where kaimahi were informed a child had been moved to a new placement after they had left the house with their social worker for a visit with whānau. Secure residence kaimahi also told us there is poor planning, and limited resources and funding to support rangatahi to transition from the residence.

“[Success in the transition space is] having people who are willing to work with the kids. What are we willing to put into our kids before [they get here to residence]? It feels like [Oranga Tamariki and the system] are asking, ’Are they [rangatahi] worth that much resource or funding?’ … [That’s the] reality for them.” – Residence kaimahi

Some whānau with rangatahi in residences also told us they were not updated by social workers about the transition plan for their rangatahi, which meant that they did not know what would happen after their rangatahi left the residence.

“[Youth justice social worker] actually hasn’t told me [what the plan is]. She told the judge she had all these people, but she didn’t speak about what he [rangatahi] was actually going to do.” – whānau

A lack of respite care options is risking caregiver burnout

A lack of respite care options was also raised by a couple of government agencies, with a wide range of caregivers sharing mixed experiences on access to regular respite.

We heard when caregivers cannot get respite, they cannot attend family emergencies. We also heard one case where emergency caregivers had to take a newborn while sick. Some caregivers told us they are at risk of “burning out” or have threatened to stop being caregivers.

“The other thing that is really missing is respite care. We only have one respite place in Tauranga and the waitlist is one year. Our māmā are needing a break and respite is [meant to be] preventative, so nothing escalates.” – Health kaimahi

Incomplete referrals from Oranga Tamariki impacts the support organisations can provide to and their

Some community organisations voiced concerns about a lack of information in referrals from Oranga Tamariki, impacting on the support they can provide and the quality of their engagement with , rangatahi and whānau.

A transition to adulthood provider explained that Oranga Tamariki social workers should refer rangatahi with a plan in place, but a lot of the time this doesn’t happen, so they have to start “from scratch”. They and another community organisation spoke of getting empty All About Me plans alongside referrals from Oranga Tamariki, or plans with out-of-date information. We heard this means they have to “hunt down” social workers or rangatahi, who can both be difficult to contact.

A couple of community organisations emphasised the importance of a fulsome and high-quality referral to their services. They told us that the motivation of rangatahi and whānau to engage is highest when the social worker referring them knows them well and they voluntarily sign up, rather than feeling required to use the service. One kaupapa Māori organisation said they will send referrals back if they are missing information. They explained that without this information they don’t know whether they can provide the right services to meet the needs of tamariki and rangatahi, particularly when they are not made aware of disabilities or high and complex needs.

“Oranga Tamariki want to push that rangatahi or tamaiti [child] out really quick, so they don’t complete a real informative referral. And we say ‘nope’, we send back all the information we need. We want the plan, the rangatahi needs, and until we get that information we won’t pick it up. I will tell [kaimahi] ‘hold up’ if they get asked to engage, and I will intervene and I will wait until we have the goods to provide a good service. Even when kids come into care, I want to know everything. I want to know what has been done, have they gone to therapy etc.” – Kaupapa Māori organisation kaimahi

Transition to adulthood services feel transition support is not prioritised by Oranga Tamariki due to a lack of communication and awareness of the services they provide

Many rangatahi spoke positively about the support they receive from transition to adulthood kaimahi, highlighting both the emotional and practical support they provide.

“She’s amazing. She’s like the mum you didn’t have, you know ... Growing up I didn’t really have any parental guidance, and she showed me a lot of that guidance ... She’s amazing.” – rangatahi

“They helped with my CV, getting into study, helped with my licence. Oranga Tamariki have taken so long to help with anything, they are so slow.” – rangatahi

“... They let you step into adulthood and they’re there when you need them.” – rangatahi

A number of different transition to adulthood providers spoke of the long-term tailored support they provide to help rangatahi prepare for adulthood. Examples highlighted the strong and tangible positive impact they saw in rangatahi. These kaimahi helped rangatahi address unstable housing and finances, illicit substance use, and provided support to plan positive future goals. Some helped rangatahi navigate youth justice arrests. The kaimahi also highlighted their role in “networking support” for rangatahi by communicating with different providers both within and outside the region.

“Scary times for our rangatahi. Just the transition to adulthood service itself - we need to protect this service. People get focused on the successful stories [after rangatahi get support from transition services] but they don’t look at the journey. All the little things [transition kaimahi do] that don’t get seen. We need to celebrate that. The really individualised support and rather than them being a one size fits all service, so many kids really need this service.” – Transition to adulthood kaimahi

However, a couple of kaupapa Māori organisations and social service providers felt that transition to adulthood is not a priority for Oranga Tamariki. Regular face to face are no longer taking place and only sparse updates about critical issues are being communicated. A kaimahi noted that they haven’t heard from Oranga Tamariki in a month.

This perception is further reinforced by services emailing Oranga Tamariki to advise them of eligible rangatahi. These emails have helped increase awareness at local Oranga Tamariki sites about the transitions service, and the benefits of referring rangatahi, which may lead to earlier proactive referrals in future. A few Oranga Tamariki site leaders said they “encourage” social workers to offer transition to adulthood referrals to eligible rangatahi, with one site leader noting it is compulsory that they offer these referrals to eligible 15-year-old rangatahi.

Representatives from iwi and an NGO said the disestablishment of the Senior Advisor Transitions role at Oranga Tamariki has negatively impacted on their communication. They no longer have a single contact to report to. We heard how the senior advisor ensured consistency of meetings and would “hold everything”, including answering any questions transition kaimahi may have. We were told that a helpline has replaced the senior advisor role, but that it lacks local knowledge and the positive and strong relationship of a consistent contact.

We heard rigid thresholds to access support is resulting in and not participating in education

Some government and community organisations spoke about how difficult it is to access support for tamariki and rangatahi with high and complex needs or disability needs so they can remain engaged in education. We were told that the high thresholds for government funding means many tamariki and rangatahi cannot access support.

For example, we heard that support from the High and Complex Need unit in Whakatāne, though working well for those who can access it, requires tamariki or rangatahi to first be enrolled in school and has a high threshold to be eligible.

“What about our children who don’t meet [High Complex Needs] unit threshold? They’re in the middle, they’re getting missed.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

In another example, some Health and Alternative Education kaimahi told us that referrals for Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLBs) through the Te Kahu Toi panel (also referred to as Intensive Wraparound Service; IWS) cannot be made by them or but must come from someone in education. However, for these referrals to be made by education kaimahi, strong advocating is required through a complex process that is “intrusive” to whānau. This process includes evidence that support from all other avenues and agencies have been “exhausted”. As context, we were told that numerous attempts for support through Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (ICAMHS) does not always meet the evidential requirements of an exhausted search. The complexity of the Te Kahu Toi process, combined with the requirement that only education kaimahi submit referrals, has led to an inconsistency in when schools send referrals. Some schools are delaying making referrals for an RTLB while waiting for paediatrician reports or making late referrals for rangatahi who could have been receiving support from a younger age.

When support is not available to tamariki or rangatahi we heard that they can be left without access to education. We heard about tamariki who had been out of education for two or three years, despite ongoing meetings between Oranga Tamariki disability advisors and the Ministry of Education to try and implement support. Health kaimahi told us that a lack of support for Autism Spectrum Disorder and Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder means tamariki and rangatahi with these disorders are often unable to be enrolled in school. Where we did hear about tamariki and rangatahi with these disorders receiving educational support it was having a strong positive impact, though caregivers and school kaimahi noted that the support is still limited by funding.

“It was a fight to who was funding [a teacher aide]. We were in the middle and we were just thinking we just want him to go to school. They [Oranga Tamariki and Ministry of Education] both knew he needed it, but no one wanted to fund it. Ministry of Education can only do high needs if they meet the threshold /criteria for funding for 16 hours and Oranga Tamariki has to fund the rest, which they’ve now agreed to do.” – Non-whānau caregiver

Some Health and NGO kaimahi said there are two-to-three year waitlists for neurodiverse tamariki and rangatahi to be diagnosed, after which finding support is a further “struggle” due to limited availability and long waitlists for health services.

School kaimahi said there are no educational psychologists for them to refer to and “the longest waitlists” for tamariki and rangatahi with high and complex needs. They described that getting support from the Ministry of Education was sometimes like “getting blood out of a stone”. They gave an example where a school kaimahi pre-emptively applied to the Interim Response Fund (IRF) for support for a child that was transferring to their school. This child had a history of behavioural concerns including physical violence, however they were unable to access support through the IRF fund without an incident having occurred at the school itself. A couple of school kaimahi recognised that the Ministry of Education is underfunded and that continued funding cuts from successive changes in government have ultimately resulted in education being a “system of frustration” that is not child centred.

“We talk about the kids being the centre of these decisions but it’s not always possible because you are caught in these systems. If we peeled it back and paused a bit, in order for a kid to be happy they just need a place to chill. We just need to chill a little bit, we can call it a collaborative action plan sure, we just need to do our best by these kids, but we cannot do that in a class of thirty with one teacher.” – School kaimahi

Many rangatahi are better supported in Alternative Education and employment pathways than in mainstream education, but there are limited services available and barriers to their accessibility

Kaimahi from Oranga Tamariki and community organisations told us that the overwhelming majority of tamariki and rangatahi they work with do not attend mainstream school and do not want to. They know how important it is for tamariki and rangatahi to be actively engaged in some form of education or employment, sharing concerns that those who are not are more likely to become involved with youth justice. However, we were told that the lack of resource within the education system has created a “dire” situation that has led to mainstream schools having to exclude or expel tamariki and rangatahi who do not have the support they need. We heard that many of these tamariki and rangatahi are behind in their education due to the lack of support and prolonged absences. An Oranga Tamariki youth justice kaimahi noted that half of the rangatahi they work with have little to no literacy and math skills.

We heard that some rangatahi are attending Alternative Education, with many speaking positively about their experiences and the support they receive. However, other rangatahi clearly expressed much greater interest in paid employment than education. This was also understood by Oranga Tamariki and community organisations, however one kaupapa Māori organisation expressed concern that the Ministry of Social Development had shown a “change in attitude” this year, and were pushing Alternative Education providers to get rangatahi “work ready” instead of focusing on their educational needs.

“I do Alternative Education. Course is pretty cool. It’s like school but less kids. We have a kitchen to cook us some food, pool table for us to play. There are couches out there and bean bags. There are blankets which is good because it’s cold. Course is pretty mean.” – Rangatahi

“They [Alternative Education] help us with getting [NCEA] credits to get jobs. We’ve done my CV, so applying for jobs now. Anything related to our [NCEA] levels, we go out to this thing where there are other options for us.” – Rangatahi

“I just got a job but the education [here in Taupō] isn’t that great, there’s not much more I can do here for education.” – Rangatahi

Some caregivers, whānau and community organisations expressed a need for Alternative Education options that meet the diverse needs of rangatahi. Specific examples included more focused programmes teaching skills like mau rākau (weaponry arts) and mara kai (gardening), and face-to-face options that don’t require online correspondence.

We also heard there is a strong need for alternative education options that are open to younger tamariki, aged 11-15 years. A change in policy has meant 14–15-year-olds are no longer eligible for Alternative Education, including no exemptions for that age group. We heard this leaves younger rangatahi in “limbo” if they are excluded from mainstream schools. One community organisation explained that for this age group they are looking into two options; being able to attend a course while still being enrolled in school, or seeking an Early Leaving Exemption.

“There could be more alternative options for rangatahi who can’t go back to school. There are pockets of kids who have nothing here in Rotorua for them, even in the schools there needs to be more support for the rangatahi.” – Whānau

Reliable, safe and cost-effective transport is already a barrier to school attendance, with the impact of planned funding cuts by the Ministry of Education causing concern

Some whānau, caregivers, and Education kaimahi told us that transport cost, reliability, and safety is a barrier to tamariki and rangatahi attending school.

“Buses aren’t free [and] there’s no direct bus [to high school] … The bus stops at the place where it’s not safe for them because of all the fights. Police and teachers have to wait there so nothing happens, and the girls don’t feel safe there.” – Whānau

Education kaimahi raised further concerns about imminent funding cuts by the Ministry of Education to their Regional Response Fund. Local Education kaimahi have been using this to fund Kura Waka; a school transport hub that has been “highly effective”. As the cuts to the Regional Response Fund were still being discussed at the time of our visit, any impacts were not yet clear, but there were concerns that it could negatively impact on school attendance and result in the further exclusion or expulsion of tamariki and rangatahi from education.

Schools are trying to find creative ways to meet the wellbeing, behavioural and disability needs of Tamariki and rangatahi

One school spoke positively about how Oranga Tamariki funding allows them to creatively support neurodiverse tamariki, focusing on their social needs as a more effective form of support than standard processes. However, another education service provider said they will avoid going to Oranga Tamariki for funding as it is too difficult to access. Despite these difficulties, they shared how their three core contracts allow lots of support for all tamariki and rangatahi, not just those in the custody of Oranga Tamariki. There is a particular focus on navigating the social aspects of education.

“It’s about social appropriateness for these kids who have these diverse needs, they are being taught how to behave in a social situation and we are being given the autonomy to use the funding in a creative way that is going have such an awesome effect. It is so much better than having a teacher aide sitting next to them doing a math worksheet … so I am really grateful to those who aren’t even in the education space be able to see the benefit of these creative solutions. Otherwise, you get caught up in the Gateway system. The kids want normality and fun, they’ve been through grief and all sorts of things. I’m glad we have the autonomy to be creative [using Oranga Tamariki funding].” – Education kaimahi

Te Kura (Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu, formerly known as The Correspondence School) were also positive about a change in policy that now allows them greater access to Ongoing Resourcing Scheme (ORS) funding for rangatahi with high and complex needs. Te Kura leadership described how this would allow them to better resource support for rangatahi and overcome short staffing and “offering piecemeal”.

A school we spoke with told us about the funding provided by local rūnanga, who will, for example, help pay for students’ uniforms and school fees. They also shared that they have a whānau navigator who focuses on removing barriers to attendance, including transport and mental health. For younger rangatahi with high and complex needs who they cannot support in mainstream classes, they also have an onsite Alternative Education unit. This allows them to avoid excluding rangatahi and offer individualised learning that is “relational and very community based”.

Another school told us about the long running support provided by their onsite wellbeing clinic called Whai Ora. We heard this clinic has been in place for over two decades, having been founded and still run with the support of local . By outsourcing services, the clinic can provide rangatahi access to a range of health and other services such as doctors, physiotherapists, social workers, career counsellors, mental health professionals, and neurodiversity support people.

“It gives the kids a safe space. Gives them time to recalibrate, give them a scaffolding and a space to reflect. The ongoing support system is strong. If they haven’t got anywhere to go, we’ve got friends and family that can support them … It’s not perfect, it takes a lot of energy. It was something that was set up over the years. We see the kids quite often [and we] have been given an opportunity to get some counselling around them. We want these kids still at school.” – Education kaimahi

Safety Planning at School

A few Oranga Tamariki and education kaimahi told us they want to improve their collaboration and communication in implementing safety plans. We heard schools know their tamariki and whānau well, and when they are not told about safety plans, they do not know how to protect the tamariki in their school. A few Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us they face on-going issues with some schools who do not inform them about concerns of abuse or suggest alternatives to safety plans in their classroom.

Funding to convene family group conferences appears limited and inconsistent, which is a barrier to holding culturally appropriate that support , , and

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi and leaders told us how important food is to practice manaaki and create a positive environment in a Family Group Conference (FGC). Even something as small as “a cup of tea” can remove the awkwardness and make whānau feel comfortable. We heard a lack of funding to convene FGCs is a barrier to running meetings that have safe spaces and support whānau. Some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi are concerned the inconsistent funding conflicts with their organisational values.

“Each manager has a different view. In some areas, they won’t give you anything but a jug of water … They [FGC coordinators] have to beg and beg [for funds].” – Oranga Tamariki site leader

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us site leaders decide what FGC funding they will approve for food or transport costs on a site-by-site basis. We heard some site leaders support kaimahi to provide more food, while others will only fund a packet of biscuits for a half-day FGC. Though there are regional Oranga Tamariki guidelines for FGC budgets, they have not been recently updated. We heard the current funding process is a barrier to kaimahi carrying out their role in FGCs as “cultural ambassadors” and does not support them to take culturally appropriate approaches.

“I know other sites struggle to get petrol vouchers even. I have a social worker say ’why can’t whānau attend on Teams?’ So much for whānau, whanaunga and whanaungatanga … It goes against all of our values.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

Limited availability and funding of community services are barriers to delivering the support identified in family group conference plans

We heard a lack of resources in the region is a barrier to providing the services in FGC plans. Whānau told us it can take months after FGCs to receive assessments and services, if services are able to be delivered at all. For example, we heard of a rangatahi staying in a group home longer than necessary while waiting to receive the supports that were decided on at their FGC. Some tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau told us care and protection or youth justice FGCs are “pointless” if they do not get support afterwards.

Many community providers feel they must take on the responsibility of Oranga Tamariki to ensure tamariki, rangatahi and whānau understand the FGC process and have their voices heard

Last time we visited the region, many whānau told us they felt excluded from FGC meetings and lacked a voice in big decisions. We are still hearing about these issues. Some tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau told us Oranga Tamariki did not provide timely information about their FGCs; both care and protection, and youth justice. Some whānau said Oranga Tamariki did not contact them to explain the FGC process, or they did not explain it well.

“I get an email saying you need to attend [the Family Group Conference]. Sometimes it can be the day before and if I’m not available I miss out.” – whānau

The Oranga Tamariki practice centre states the social worker and care and protection FGC coordinator hold joint responsibility to support tamariki, rangatahi and whānau during the FGC process. However, many community and government agencies told us Oranga Tamariki kaimahi do not always engage with tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau to explain FGCs or to inform them about dates. When this happens, and other government agencies feel they must pick up the responsibility to “keep whānau in the loop”. It can be stressful when NGOs are notified about FGCs the day before they happen.

“Whānau are the last to be notified about anything. I’ve told them about court dates and they haven’t been informed by Oranga Tamariki.” – NGO kaimahi

We heard the high caseloads held by many Oranga Tamariki social workers can prevent them from having the time to properly explain the FGC process to whānau. Some FGC coordinators are concerned that when they take the responsibility to work with whānau and uplift their voice, they are compromising their legislative requirement to be an “independent” worker. But when Oranga Tamariki social workers and FGC coordinators do engage with tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau before FGCs, we heard it enables them to create a safe space and uplift their voices. For example, social workers have “hard conversations” in private and ensure whānau are not surprised about the purpose of the FGC. Whānau told us it is important for Oranga Tamariki kaimahi take time to explain the FGC process and give timely updates, so whānau can feel prepared and that they have a voice.

Some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi also told us when specialists share information, it ensures the right supports are included in FGC plans. In one case, we heard having a social worker at an FGC who worked closely with a whānau member helped them be more open in sharing their needs with other whānau and the result was a more supportive FGC plan.

Consultation and a shared approach between Oranga Tamariki and Police in youth justice FGCs supports rangatahi, whānau, and victims to be involved and have their voices heard

We heard how important it is to have victims present at youth justice FGCs and their voices heard. When victims can share their experiences, and the FGC has space for rangatahi to take accountability, it can help rangatahi not re-offend.

“Victims got to run that FGC [Family Group Conference]; they showed footage of the funeral even. The impact was amazing, this young person never re-offended. I never thought we could make it a positive experience. It showed me the power of a good FGC [Family Group Conference].” – Police kaimahi

Oranga Tamariki and Police kaimahi were concerned about which participants are prioritised during FGCs. An Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us the legislation surrounding the FGC process can be a barrier to supporting victims, and also a barrier to putting rangatahi at the centre of decisions. We heard examples of Oranga Tamariki kaimahi not explaining the youth justice FGC process to whānau, or not inviting victims to the FGC. Conversely, some Oranga Tamariki social workers were said to be “youth-focused” Key theme: Family Group Conferences

and will give rangatahi “heaps of chances” to continue their plan. We also heard examples of some police officers not considering surrounding context in whether a punishment is reasonable, or whether using a more supportive measure may guide rangatahi towards more positive long-term outcomes.

Consultation between Police and Oranga Tamariki before convening FGCs enables them to help rangatahi, whānau, and victims understand the FGC process and support them during the hui. However, in some parts of the region we heard regular consultations have stopped between Oranga Tamariki and Police.

“We used to have consults, but they stopped two years ago. Now it’s an email. It’s not good … We have a big meeting on this Wednesday to sort it out.” – Police kaimahi

Police say they make considered decisions to apprehend and assess the need to use force, but some rangatahi feel they were unfairly treated by police

Frontline police officers must consider public interest and safety in their decision making. Some officers told us that age is not a relevant factor when they decide whether to use force when apprehending rangatahi.

We were told that knowledge of legislation and decision assessment tools such as TENR (Threat, Exposure, Necessity, Response; a threat assessment tool) guide police officers in making appropriate decisions about the use of force as they are “responsible for how they behave”. Support from Youth Aid assists frontline police to make decisions about how they apprehend young people. But we heard from a couple of frontline officers that they are not always confident in using their powers under the Oranga Tamariki Act and are cautious of apprehending rangatahi in case they “get in trouble”.

Most rangatahi told us they experienced unfair treatment by frontline police officers during their arrest. This included accounts of being tasered, kicked, or dragged on the ground, and one rangatahi who felt as though police were “profiling”, speaking to them poorly and “getting pushy”. One rangatahi told us about having police dogs set on them while they were being apprehended, requiring medical treatment after.

“The cops were dragging us across the ground, ripping our clothes, sitting on us so we couldn’t get up. Like putting their knees to our backs on the ground … When we got put into the paddy wagon, I couldn’t breathe.” – Rangatahi

“I used to think nah we need them [Police] to help but then what I’ve been experiencing through my baby [rangatahi], I literally look at them like they’re gang members now, because they come full force. They’ll come pepper spray you, they don’t even give him a chance. They tasered him in front of me, straight into his stomach … he came flying out the room not realising that police were there. Boom, straight away tasered him.” –

Some kaimahi across the community also shared concerns around the use of force by police and the unfair treatment of rangatahi. Police practice was described by some professionals as “inconsistent” and “overly punitive” in some areas, and a couple of kaimahi felt as though some rangatahi are treated harsher than others. One professional told us they feel that some police “know very little” about the causes of youth offending, contributing to a punitive response.

“It almost seems like they [Police] want to see kids fail. They [kids] can have their house being raided multiple times a week at 1am, 3am. It’s certain families that Police go absolutely to town on.” – Oranga Tamariki kaimahi

Police officers try hard to explain rights, however some rangatahi still do not understand what their rights mean Some rangatahi we spoke to knew what their rights were and what was happening during their arrest, however, some rangatahi told us they did not know their rights or weren’t able to understand them.

For example, one rangatahi talked about feeling like the police did not like it when they asked about their rights and would become “grumpy” when they did.

“I didn’t really know what they said [when police explained rights].” – rangatahi

Most police officers told us they make a conscious effort to ensure young people know what their rights are. One frontline officer said they can take “hours just explaining [rangatahi] rights” and that it “takes time to make sure they [rangatahi] understand them”. Police officers recognised the tension between rangatahi knowing what their rights are versus understanding what those rights mean. Access to visual aids and communication supports, the use of age-appropriate language, and consulting with sergeants, other professionals or the child’s nominated person all support police officers to explain rights in a way that young people understand, and ensures they know what they are entitled to and what to expect in the process.

“You get some kids who just repeat what you say, and you know that they don’t know or understand. So, you have to take the time to make sure they know what it means.” – police officer

“[We try] explaining it [rights] in a way that makes sense to them. When you get our highflyers who can recite their rights, it is making sure you know what they [are] saying and what it actually means … You make sure they always understand their rights.” – police officer

A practice shift in Police to a holistic and preventative approach, including Te Pae Oranga process, is working well to provide wraparound support to rangatahi and reduce reoffending

Police leadership and specialist police teams emphasised the importance of addressing the root causes of youth offending and noted there has been a shift in police practice towards a holistic, preventative approach when working with young people who offend.

A couple of police in leadership roles told us they have worked across stations to prioritise connecting rangatahi with services that are available in the area they live, instead of where the offence was committed. This has ensured there are fewer barriers to accessing support, and rangatahi can better engage with wraparound services that will address their offending. Likewise, we heard from some specialist police and prevention teams that their police practice has evolved into a holistic approach, and they are supporting other police officers in understanding these perspectives. For example, training between frontline police officers and Te Pae Oranga has helped frontline officers understand what is involved in the Te Pae Oranga process.

“We’re taking more of a holistic approach where before it was punitive … Across the board for Police in terms of holistic and punitive, we’ve become more [of a] social work type style.” – police officer

“We look at that whole whānau not just the person. We never used to do that before. We were the ambulance at the bottom and its now about prevention.” – police officer

A couple of police in leadership roles told us that using alternative action pathways, such as Te Pae Oranga, and partnering with kaupapa Māori and social service providers has been largely successful in addressing the root cause of youth offending. We heard that in one area, Te Pae Oranga has had an “85 percent success rate”. Looking at Police data for the region, 2 percent of rangatahi in Rotorua are referred to Te Pae Oranga, compared to 0.3 percent nationally. Additionally, a member of police leadership told us that police “do a lot of work keeping young people out of court by using alternative actions” and that this is driven by youth aid teams using resources creatively.

“I’ve noticed it’s a much more holistic thing [working with kaupapa Māori services], as opposed to when we were referring to more mainstream providers, it tends to be that you do a lot of work with young people then if they go back to the same environment - ‘can we expect a different outcome?’ So, it’s becoming more about the wider issue … From what I’ve seen, a lot of the problems are actually health or learning issues, and some of the offending is out of frustration.” – police leader

“When they come to Te Pae Oranga we delve into their background. Sometimes the panel get to know more info than the police, such as dynamics of whānau and their whakapapa. All we hear is the kino [bad] side. We tailor a plan based around what’s good for the whānau and from a police perspective to prevent them from re-offending.” – police officer

“I think for majority of young people we deal with, if they go through an alternative pathway programme, and it works, we don’t see them later on with more serious offending.” – police leader

We heard from some whānau that Te Pae Oranga has been a positive experience for their rangatahi, who have been able to access counselling services and re-engage with education.

“It’s been great they have been doing Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Pikiao counselling, it’s good for her, her attendance at school is now up because it’s in her plan.” – whānau

“Just the fact you can openly talk, and you say how it is [at Te Pae Oranga]. They can see where things have gone wrong. They are like whānau, even the cop was alright.” – whānau

We were told some Police areas have been slower to move into the prevention space and that how to do this is still evolving. Work is still underway in some areas to build partnerships with kaupapa Māori organisations and iwi social service providers, as well as establishing Te Pae Oranga as an alternative action pathway. We were told that there is added difficulty to move towards a holistic, preventative approach in some areas, due to a lack of appropriate services to refer rangatahi to.

Police rotation policy affects relationship building and creates inconsistency

The rotation of police roles can also contribute to inconsistent views on how to work with rangatahi. We heard that police develop the skills, experience, relationships and perspectives to work with rangatahi and are then rotated out of the role. This was echoed by a couple of , with one NGO leader expressing that the turnaround of police kaimahi with different views creates ongoing disagreement in how to work with rangatahi who have offended.

“Their [police] views. It’s been a struggle. They have such a high turnaround and we build a good working relationship with the teams, and then they bring in new workers who impose their own world view on how we should be working with our people and so we clash.” – NGO leader

Some organisations are working hard to embed in their practice to support the cultural needs of , and Māori

Most emphasised the need for their workforce and practice to reflect the needs of their community and spoke of their leadership teams helping shift practice on the ground to reflect a culturally competent approach. This ensures kaimahi are better equipped to work with tamariki, rangatahi and whānau Māori and support their cultural needs.

“We do have really good support from our kaumātua, but we have really good understanding that it’s important Māori work with Māori. We have a new kaiwhakahaere starting on Monday. We have had people who naturally have the cultural position but the new kaiwhakahaere will be able to provide that stable support for the cultural lens.” – NGO leader

“We look at how we can implement te ao Māori into the organisation and then we come back and implement that within teams. My team is really responsive, tupu tahi means working alongside somebody and you are both bringing something along together to work the practice.” – NGO kaimahi

Kaimahi across the community told us they felt supported to be culturally safe in their practice, and that they can call on advisory groups and support roles for advice and guidance in working with tamariki, rangatahi and whānau Māori.

“I see [Pou Kōkiri] engage with families on a daily basis to ensure is kept. I appreciate her, as a non-Māori, to talk to her and get advice from her as she keeps me safe [in te ao Māori space].” – Health kaimahi

“We have a Māori Roopū, and no cultural decisions are made without going through that Roopū and they discuss all things Māori or if it’s about clients or trainings.” – NGO leader

Some organisations told us that embedding te ao Māori into their practice ensures they seek opportunities for tamariki, rangatahi and whānau to engage with support that is relevant for them, including opportunities to learn about their culture and identity, such as learning pepeha, whakapapa and visiting marae. Focusing on a te ao Māori approach gives space for building meaningful relationships with tamariki, rangatahi and whānau, understanding and embracing who and where they are, and encouraging them on their journey.

“It’s about helping them [tamariki and rangatahi] along the way, showing them where they can go and what they can do.” –NGO kaimahi

“We always welcome whānau in with mihi whakatau, and initially its always about whakawhanaungatanga, who they are and how we can connect, then when finished we have a mihi whakamua [kōrero to discuss moving forward with whānau].” – Kaupapa Māori organisation kaimahi