Aroha

Aroha is vital for and to feel safe and develop emotionally. Aroha is achieved when tamariki and rangatahi feel loved, supported, safe and cared for, and they can receive love and give love to others (reciprocity).

Without aroha, tamariki and rangatahi risk experiencing negative life outcomes, including abuse and trauma, poverty, and poor health.

The require actions to be taken in response to an allegation of abuse or neglect for tamariki or rangatahi in care. The NCS Regulations also require safety needs to be assessed as part of an overall needs assessment, and for needs assessments and plans to specify how often tamariki and rangatahi need to be visited by their social worker. The NCS Regulations require planning to take place for any transition, including returning home or transitioning to a new placement.

Most and indicated that they feel safe, supported and cared for. In line with what we heard last year, most of the tamariki and rangatahi we spoke with mentioned caregivers, social workers, siblings, parents or workers in the residence/home as people who supported them, or they could go to if they needed to.

However, over the past three years, despite a decrease in the number of tamariki and rangatahi in care, an increasing number of tamariki and rangatahi in care are being abused or neglected. There has also been no improvement in the frequency of social worker visits, despite this being raised as a concern in our reports, and assurances from Oranga Tamariki that this would be a priority. There are barriers that limit social workers from being able to see tamariki, rangatahi and caregivers. In the Manaakitanga chapter, we found similar gaps in the level of support for caregivers.

Oranga Tamariki are not always assessing caregivers and their household before tamariki and rangatahi are placed with them. When we raised this issue last year, Oranga Tamariki committed to improving practice, however, we are yet to see the impact of this. Oranga Tamariki data shows that transitions within and out of care are reducing, which suggests an improvement in stability. However, availability of suitable homes, poor information sharing with caregivers and the availability of respite care are barriers to further improvement. As noted in our chapter on Manaakitanga, we also heard from caregivers that support to care for, and meet the needs of, tamariki and rangatahi is insufficient.

Abuse and neglect

N/A - 2020/2021

1,367 - 2021/2022

1,754 - 2022/2023

not measured - 2020/2021

not measured - 2021/2022

47% - 2022/2023

Oranga Tamariki made a “no further action” (NFA) decision in relation to 148 reports of concern for tamariki and rangatahi in care. Through its review process, it found that 69 of the NFA decisions (47 percent) were incorrect. Oranga Tamariki informed us that a new process has been in place since November 2022, with incorrect NFA decisions being re-entered into the system and followed up by an assessment or investigation. NFA decisions are reviewed within a week of being made. Under this new process, 12 percent of "inappropriate" NFA decisions for tamariki and rangatahi in care, have not been remedied by Oranga Tamariki this year.

N/A - 2020/2021

1,230 - 2021/2022

1,606 - 2022/2023

742 - 2020/2021

711 - 2021/2022

895 - 2022/2023

The above data shows that findings of abuse and neglect of tamariki and rangatahi in care have increased since 2020/2021, despite fewer tamariki and rangatahi in care. It's important to note there may be multiple findings of harm of a child. In 2022/2023, there were 895 findings of harm relating to 519 tamariki and rangatahi.

31% - 2020/2021

22% - 2021/2022

33% - 2022/2023

This measures the proportion of investigations and assessments for tamariki and rangatahi in care that were completed within 20 working days, which is Oranga Tamariki policy. We note that Oranga Tamariki policy was amended in 2022 to complete investigations within 40 days, if the circumstances are complex.

61% - 2020/2021*

47% - 2021/2022**

71% - 2022/2023

* Oranga Tamariki revised this figure and it differs from the 62% published in previous Experiences of Care in reports for the same period.

** Oranga Tamariki revised this figure and it differs from the 43% published in Experiences of Care in Aotearoa 2021/2022 for the same period.

This year shows an increase in the proportion of caregiver support plans being reviewed following an allegation of abuse or neglect of tamariki or rangatahi in their care. The review of the caregiver plan does not necessarily mean the caregiver was responsible for the alleged abuse or neglect, but rather that the caregiver has support to address ongoing impacts of the abuse or neglect experienced by the tamariki or rangatahi they care for.

Social worker visits

60% - 2020/2021

59% - 2021/2022

61% - 2022/2023

59% - 2020/2021

62% - 2021/2022

65% - 2022/2023

Assessing safety needs and planning

77% - 2020/2021

88% - 2021/2022

94% - 2022/2023

Under the , an assessment of safety needs must be undertaken for all tamariki and rangatahi when they come into care, and any needs arising out of this assessment be included as part of the plan prepared for the tamariki or rangatahi.

As part of its new self-monitoring framework, Oranga Tamariki developed a lead indicator ”safety needs”, that looks at whether safety needs are incorporated into tamariki and rangatahi plans.

It is also relevant to note that while safety needs are assessed on entry to care, they can change over time and this assessment is not related to the measures for allegations of abuse and neglect in care (NCS Regulation 69).

N/A - 2020/2021

66% - 2021/2022

67% - 2022/2023

This measures whether caregivers were approved (either fully or provisionally) prior to tamariki and rangatahi being placed with them.

60% - 2020/2021

89% - 2021/2022

85% - 2022/2023

This measures whether, for the around half of transitions that are planned, sufficient planning has occurred to support a successful transition between care options.

Motel accommodation

There has been a marked reduction in the number of tamariki and rangatahi staying in motels and the length of those stays. This year, 135 tamariki or rangatahi spent a total of 2,043 nights in motel accommodation. The median length of stay in a motel was two nights (one child/young person spent 167 nights in motel accommodation). This is a marked improvement on 2021/2022, when 186 tamariki or rangatahi spent 6,151 nights in motel accommodation, with the longest stay exceeding two years.

A key finding in our 2020/2021 report was that Oranga Tamariki responds well when first enter care, with practice weakening over time. In response to this finding, Oranga Tamariki told us that the Office of the Chief Social Worker would continue to focus on better understanding social worker capacity, caseload complexity and workload management, while supporting frontline kaimahi with improved supervision support. It would also simplify core processes and systems, and redirect tasks that do not require a social work skill set, so that social worker time can be refocused to working directly with tamariki, , and caregivers. Oranga Tamariki also told us that the tools and resources it is developing for kaimahi will allow social workers to spend more time with tamariki, rangatahi, whānau, caregivers and communities, and that positive change is underway and it expects to see this continue. Despite these undertakings, we see no evidence of improvement in the frequency of visits with tamariki and rangatahi in Oranga Tamariki data or in what we heard in communities.

In our 2021/2022 report, we found that not all caregivers were approved prior to tamariki or rangatahi being placed with them. In response, Oranga Tamariki noted that it would remedy this with urgency, and that it expected to see improvements within six months because of better understanding of the policy and practice guidance. However, the Oranga Tamariki data this year shows that there has been no change to the proportion of caregivers who are approved (either fully or provisionally) prior to tamariki or rangatahi being placed with them. Around a third of all tamariki are placed without any approval in place.

Most and indicated that they feel safe, supported and cared for. In line with what we heard last year, most of the tamariki and rangatahi we spoke to this year mentioned caregivers, social workers, siblings, parents or workers in the residence/home as people who supported them, or they could go to if they needed to. This is aligned with the finding from Te Tohu o te Ora, which found that 98 percent of the tamariki and rangatahi surveyed thought the adults they live with now looked after them well.

Like last year, many tamariki and rangatahi talked positively about being cared for, being safe, and being supported by kaimahi and caregivers in residential settings, however, a few rangatahi in care and protection residences or group homes said that they didn’t feel supported or cared for in that situation.

Allegations of abuse and neglect

Reported rates of harm to tamariki and rangatahi in care are not reducing

While we heard from tamariki and rangatahi that they feel safe, Oranga Tamariki has told us that 2,558 reports of concern were recorded for tamariki and rangatahi in care during this reporting period. Of these, 1,754 were considered allegations of Tamariki and rangatahi in care found to have been harmed harm (abuse and neglect). In 2021/2022 there were 1,894 reports of concern and of these 1,367 were considered to be allegations of harm.

In addition to an increase in allegations, there was also an increase in findings of abuse and neglect.

Tamariki and rangatahi in care found to have been harmed

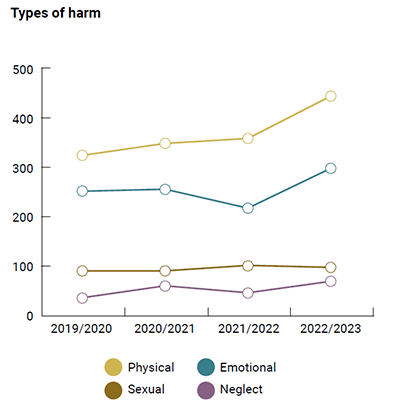

| Year | Children | Findings | Physical | Emotional | Sexual | Neglect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2019/2020 |

411 |

690 |

320 |

248 |

88 |

34 |

|

2020/2021 |

486 |

742 |

344 |

252 |

88 |

58 |

|

2021/2022 |

453 |

711 |

354 |

214 |

99 |

44 |

|

2022/2023 |

519 |

895 |

439 |

294 |

95 |

67 |

Notes: Data is reported for all tamariki and rangatahi in care with findings of harm.

A child may have multiple findings of harm.

Number of tamariki and rangatahi found to have been harmed by person alleged to have caused the harm

| Year | Family/ whānau caregiver | Parent as caregiver | Non- family/ caregiver | Staff | Another child in placement | Another child not in placement | Parent not as caregiver | Adult family member | Non- related adult | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/2020 | 122 | 50 | 52 | 22 | 33 | 17 | 44 | 36 | 90 | 3 |

| 2020/2021 | 104 | 82 | 65 | 37 | 49 | 23 | 39 | 46 | 83 | 23 |

| 2021/2022 | 108 | 59 | 43 | 43 | 74 | 26 | 35 | 47 | 63 | 23 |

| 2022/2023 | 97 | 93 | 37 | 38 | 116 | 40 | 56 | 59 | 66 | 20 |

Notes: Data is reported for all tamariki and rangatahi in care with findings of harm.

Children are counted for each category they are found in.

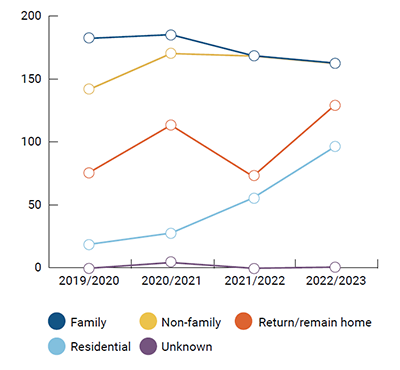

| Year | Family | Non-Family | Return/Remain Home | Residential | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/2020 | 183 | 142 | 76 | 19 | 0 |

| 2020/2021 | 186 | 171 | 114 | 28 | 5 |

| 2021/2022 | 169 | 169 | 73 | 56 | 0 |

| 2022/2023 | 163 | 163 | 130 | 97 | 1 |

Notes: Data is reported for all tamariki and rangatahi in care with findings of harm. Children are counted for each category they are found in. There may be multiple findings of harm relating to one child. This means the number of findings by placement type may total more than the number of tamariki and rangatahi.

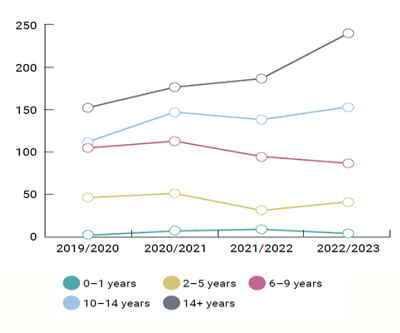

Tamariki and rangatahi with findings of harm by year and by age group

| Year | 0–1 | 2–5 | 6–9 | 10–14 | 14+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/2020 | 2 | 46 | 104 | 111 | 151 |

| 2020/2021 | 7 | 51 | 112 | 146 | 175 |

| 2021/2022 | 9 | 31 | 94 | 137 | 185 |

| 2022/2023 | 4 | 41 | 86 | 152 | 238 |

Initial decision making

Oranga Tamariki policy states that, when an allegation is made that tamariki or rangatahi “are being, or are likely to be, harmed”, the allegation must be recorded as a report of concern. Most allegations are recorded as a report of concern by the National Contact Centre, with some recorded by Oranga Tamariki sites.

After a report of concern has been recorded for tamariki or rangatahi in care, Oranga Tamariki makes one of three decisions:

-

Take no further action (NFA). This decision is taken when the report has no substance, the concerns do not indicate harm to a child, or concerns are being appropriately responded to by others.

-

Carry out a child and family assessment. This decision is appropriate if the tamariki or rangatahi is experiencing (or is likely to

experience) serious harm, and/or the concerns are having a significant impact on their development, safety, health and/or wellbeing, but do not indicate abuse that may constitute a criminal offence.

-

Carry out an investigation. This decision is appropriate when the concern for the child meets the criteria in the Child Protection Protocol and the abuse may constitute a criminal offence.

Oranga Tamariki data shows that, of the 1,754 reports of concern that it considered to be allegations of harm in 2022/2023:

-

an initial decision for an assessment or investigation was made in 1,606 cases

-

no further action was initially taken in 148 cases.

Oranga Tamariki reviews all NFA decisions about allegations of abuse and neglect for tamariki and rangatahi in care as part of its quality assurance checks, and this is done weekly. These reviews found that 69 of the 148 NFA decisions (47 percent) were incorrect. This is a similar proportion of incorrect NFA decisions as last year (45 percent).1

This year, Oranga Tamariki informed us that a new process has been in place since November 2022, all NFA decisions are reviewed within a week, and incorrect decisions are re-entered into the system and assessed or investigated. As a result, the following actions were taken:

-

61 of the 69 incorrect NFA decisions were re- entered and assessments completed.

-

The remaining eight did not receive an assessment or an investigation, and as such remain inappropriate NFA decisions. The main reason for this is a delay between Oranga Tamariki receiving the report of concern and making the NFA decision, and when this was picked up by reporting.

After assessments or investigations had been completed, 12 percent of “inappropriate“ NFA decisions were not remedied by Oranga Tamariki this year.

In total, 95 percent of all allegations of harm this year proceeded to assessment or investigation. This leads us to question whether there is value in making an initial response decision (particularly when half of the NFA decisions were incorrect), or if a more appropriate response would be to complete an immediate assessment or investigation.

Oranga Tamariki compliance with Regulation 69 is improving over time

NCS regulation 69 requires that when an allegation of abuse or neglect is made about tamariki or rangatahi in care, it is responded to promptly, the information is recorded and reported in a consistent manner, the tamariki or rangatahi are informed of the outcome (if appropriate) and steps are taken with the parties to the allegation, including a review of the caregiver’s plan.

Oranga Tamariki compliance with Regulation 69 has improved in some areas and remained static in others.

The data below compares findings for 2020/2021, 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 on whether the initial response at the site was prompt, whether the standard of completing the assessment or investigation within 20 working days was met, whether findings were entered correctly, and whether all information relating to the allegation was entered correctly into the Oranga Tamariki database.

87% - 2020/2021

84% - 2021/2022

80% - 2022/2023

31% - 2020/2021

22% - 2021/2022

33% - 2022/2023

90% - 2020/2021*

90% - 2021/2022

86% - 2022/2023

* Oranga Tamariki revised this figure and it differs from the 91 percent published in previous Experiences of Care in reports for the same period.

45% - 2020/2021

53% - 2021/2022

63% - 2022/2023

Timeliness of investigations and assessments is getting worse

The Safety of Children in Care team reviewed the findings of 1,281 assessments and investigations between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023. For 80 percent, it found the initial response at the site office was prompt and within the expected timeframe for completing an initial safety screen. This is a decrease from the previous two years.

Following an initial safety screen, Oranga Tamariki policy is that the site is expected to complete an assessment or investigation within 20 working days, or if the matter is complex or further time is needed, it must be completed within 40 working days.

Oranga Tamariki found that 33 percent of assessments and investigations met the standard of being completed within 20 working days. This is an improvement on previous years.

Timeliness was raised by the Police kaimahi we spoke with. They told us about what they perceived as a lack of action in response to reports of concern in general. In one region, we were told it could be a wait of between two to three weeks for the allocation of a local social worker after a report of concern was lodged with the Oranga Tamariki National Contact Centre. Often these reports of concern were made after a family harm call out. While these did not specifically relate to tamariki and rangatahi already in care, they noted that this delay was a barrier to early intervention:

“We are missing the opportunity to have effective, preventative measures put in place for them. We look at ‘who is the lead agency’ and OT is just not there. Police become the twenty-four- hour preventive [agency] and end up doing everything.”

We also heard from Caring Families Aotearoa about the impact on caregivers and tamariki when there are lengthy caregiver investigations, particularly when tamariki or rangatahi are placed outside of their care during this time. Where it is necessary to move tamariki or rangatahi from their placement while the investigation takes place, we heard that the longer the investigation takes, the more difficult it becomes to return tamariki to the caregiver’s home, if this is considered appropriate. Caring Families Aotearoa felt that two weeks was the longest a tamariki or rangatahi could be away before it has a detrimental impact on a subsequent return.

Caring Families Aotearoa also raised concern about the lack of learning following an investigation to determine whether preventative measures, such as providing more support when caregivers have reached out, could have stopped the alleged harm from occurring.

Caring Families Aotearoa also told us that in its experience, many social workers investigating allegations are not experienced in doing them and are unfamiliar with the policy framework as they don’t do them often enough. Having a specialised team, or specifically trained person in each site to do these investigations could be beneficial.

The perception of Caring Families Aotearoa was that Oranga Tamariki prefers a highly risk-averse approach; that often a knee jerk reaction is made to remove the child immediately following an allegation, instead of making a more considered and holistic approach, which may include a safety plan. Oranga Tamariki policy states “Wherever it is safe to do so, we must support, strengthen and assist the whānau or family to care for their tamariki and prevent the need for them to be moved to an alternative living arrangement.” Removing the tamariki or rangatahi immediately takes the pressure off completing the investigation within timeframes, as safety of the tamariki or rangatahi is no longer a perceived issue, but this can be detrimental to the tamariki or rangatahi, creating unnecessary and unsettled placements.

Ministry of Education kaimahi also spoke about stability and how the response to allegations can have an impact on this. For example, they spoke about a case where the disclosure of abuse with a whānau caregiver led to the tamariki cycling through multiple short-term family home placements, before ending up with a non-whānau caregiver. They highlighted issues around information sharing between agencies, and how these can be exacerbated if care changes result in a change in school, particularly if relevant background information is not shared with the new school to assist with understanding and meeting the needs of the tamariki or rangatahi.

“[The] school wasn’t listened to enough to what we experienced, system wasn’t up front enough … [if] schools don’t have time to build connection and trust, the kids are considered naughty [when they] move classes and regions because of placement availability.”

Further, some caregivers told us they felt they were not supported enough by Oranga Tamariki to meet the needs of the tamariki and rangatahi in their care Tamariki/rangatahi plans reviewed who had experienced abuse while with previous caregivers. A caregiver expressed frustration that this history was known to their agency but was ”never passed to us”.

Review of caregiver plans following an allegation of abuse has improved

Once an allegation is being assessed or investigated, the require Oranga Tamariki to take appropriate steps, including a review of both caregiver and tamariki and rangatahi plans. This year, there was a continued improvement in reviews of caregiver plans, which occurred 71 percent of the time, compared with 47 percent in 2021/2022 and 61 percent in 2020/2021.

The other relevant measures remain high, with tamariki and rangatahi plans being reviewed 91 percent of the time, compared with 88 percent in 2021/2022 and 86 percent in 2020/2021, and supports are in place to address harm 84 percent of the time, compared with 81 percent in 2021/2022 and 82 percent in 2020/2021.

Letting tamariki and rangatahi know about the outcome of an assessment or investigation

Informing tamariki and rangatahi of the outcome of an assessment or investigation is necessary so they feel that they have been heard and that the concerns were taken seriously. Oranga Tamariki data shows that, in cases where it is appropriate to tell tamariki and rangatahi of the outcome, practice has increased from 33 percent in 2020/2021 to 42 percent in both 2021/2022 and 2022/2023. Oranga Tamariki advise that apart from age considerations, tamariki and rangatahi should be told in all but exceptional circumstances. Allegations of abuse and neglect for younger tamariki is low, therefore it is expected that a greater percentage of tamariki are told the outcomes.

86% - 2020/2021

88% - 2021/2022

91% - 2022/2023

82% - 2020/2021

81% - 2021/2022

84% - 2022/2023

61% - 2020/2021

47% - 2021/2022

71% - 2022/2023

33% - 2020/2021

42% - 2021/2022

42% - 2022/2023

Oranga Tamariki practice requirements

Oranga Tamariki developed a set of 12 practice requirements that, if followed, would assure it is compliant with NCS Regulation 69. Data shows that for the period 1 July 2022 to 30 June 2023, performance against the 12 practice measures to meet NCS Regulation 69 has improved, but still has not been achieved for the majority of tamariki or rangatahi who have allegations of abuse or neglect.

Compliance with the 12 practice measures was found in six percent of cases, which is an improvement from 2021/2022 when there was compliance with one percent of cases. Thirty-eight percent of cases this year met ten or more practice measures. Although there is evidence of continuing improvement in practice, Oranga Tamariki acknowledges that there remains a need to significantly improve its practice in this area.

Social Worker visits with tamariki and rangatahi

Frequency of social worker visits with tamariki and rangatahi has not improved

Social worker visits help keep tamariki and rangatahi in care safe. Regular visits enable social workers to see firsthand how things are going, and whether plans are being implemented, including actions to address safety needs. In addition, regular and quality engagement is more likely to create a trusting relationship where the tamariki and rangatahi feel safe to discuss their concerns and needs with their social worker. To this end, the NCS Regulations require that needs assessments and plans for tamariki or rangatahi must identify how often they must be visited.

“She [OT social worker] barely comes and sees me… She rings me and tells me that she is meant to see me weekly. But this doesn’t happen.”

“[I] don’t like a new social worker every month, very very frustrating, very annoying, gotta tell them same things every time, I dunno how they’ll fix that but it’s very annoying, they visit and then say there’s a new social worker for you. Why I get a new one every month?”

“Youth Horizons are a really good support team. If you were just under [Oranga Tamariki] you would only see them [social worker] every 8 -10 weeks. I’ve always been under Youth Horizons. They are only a phone call away. They visit every week. This new lady is excellent. She will ring and say “are you home? Should I pop over and take [the boys] to the park?”. One time she picked them up after school because I had an appointment I needed to get to.”

“She [Key Assets Social worker] has mother wings – he is screaming out for it. She gets down to his level. If he wants lunch, she will take him out. He also knows how hard she worked for him to make the placement work. She puts in the extra effort, he sees that. Also, the things he has asked for he has seen in his plan. She has also gone out of their way to support his siblings.”

The Oranga Tamariki lead indicator for seeing and engaging tamariki also shows that there has been no improvement in regular engagement over three years of our reporting. This was 61 percent this year, 59 percent last year and 60 percent in 2020/2021. However, when visits do occur, Oranga Tamariki case file analysis shows improvements in the quality of engagement between social workers and tamariki and rangatahi compared with previous years. Evidence of quality engagement includes whether the practitioner has (where appropriate and practical) engaged with the child in private to enable them to express their views freely, and has talked with the child about what’s happening for them, what’s going well and what’s not.

“I have a social worker, but he is as useless as a chocolate tea pot. When he is asked to make critical decisions, he is not good.”

“Her name is [name] but she’s cool, she does heaps for me. She sorts out my clothes – like when I first came here, I didn’t have time to pack my bag or get my clothes cos they had to fly me straight up. I just had what I was wearing. She sorted out clothes and stuff. I wish I could have filled my drawers you know. She asked if I needed blankets, but we’ve got heaps here so that was fine. If I want to get into boxing, she will organise that. She sorts out school stuff. She just got me a new computer, I’m pretty sure that was her.”

“Communication with OT is the worst ... The worst part was when they moved me to another social worker, but I didn’t know anything about it. Sometimes [I couldn’t get hold of them], or a delay in a message from them … I had a good relationship with one of the social workers.”

In response to our two previous reports, we were told about Whiti (a performance reporting tool) and how this would support social work practice by providing greater visibility of when visits occur.

We were also told that core processes and systems within Oranga Tamariki would be simplified and that tasks not requiring a social work skill set would be redirected, so that social worker time can be focused more on working directly with tamariki, whānau and caregivers. In addition, the Chief Social worker was looking at this issue.

“I [social worker] have been allocated to an unallocated [tamariki without a social worker]. Two of them have been in care for eight years – eleven years – and we are still involved. One hadn’t been visited for several months…”

Assessing caregivers and the safety needs of tamariki and rangatahi when they come into care

Not all caregivers and their households are assessed and approved before tamariki and rangatahi come into the home

The NCS Regulations place an obligation on Oranga Tamariki to assess a prospective caregiver and their household before tamariki or rangatahi are placed with them. Provisional approval can be given to a prospective caregiver to care for tamariki or rangatahi in an urgent situation. Assessments determine whether a caregiver is suitable and can provide the necessary care, including providing a safe, stable and loving home. Assessments are a requirement for both whānau and non-whānau caregivers. A key finding in our 2021/2022 report was that not all caregivers are being approved by Oranga Tamariki before tamariki and rangatahi are placed in their care.

It was anticipated in our last report, that the introduction of the Caregiver Information System (CGIS) from July 2022 would provide systematic (structured) information on the caregiver assessment, approval and reassessment processes every two years. However, Oranga Tamariki continued to rely on its Quality Practice Tool (QPT) and case file analysis, while it undertakes further work to validate its CGIS data. Unlike case file analysis, QPT is not systematically and randomly sampled, so it is unclear how generalisable these results are. The Oranga Tamariki lead indicator for caregiver assessment shows that there has been no improvement in assessing caregivers, and around a third of all caregivers are not approved prior to tamariki or rangatahi being placed with them, which is what we reported last year.

In its response to us last year, Oranga Tamariki noted it was concerned by the finding that caregivers were not always assessed prior to placing tamariki and rangatahi in their care. They noted it would remedy this with urgency, by reviewing when and why this is happening, and following up with practitioners to ensure the approval process is being followed. There has been no evidence of change this year, however, it may be too soon to see changes, and we will continue to monitor progress.

There is limited monitoring of provisionally-approved caregivers

The NCS Regulations provide for provisional approvals to be granted in an urgent situation with a requirement that close monitoring must take place until a full assessment is completed. This year, case file analysis again found there was minimal evidence of ‘close monitoring’ of provisionally-approved caregivers. Consistent with previous years, close monitoring was only evident in 11 percent of cases. However, we also know that the numbers of provisionally-approved caregivers have dropped over the past three years, from 55 percent in 2020/2021, to 31 percent in 2021/2022 and 13 percent this year. Given this smaller number, it is unclear why close monitoring has not improved.

Experiences of the caregiver approval process are mixed

When discussing the approval process, some Oranga Tamariki site and regional leadership kaimahi said they felt the caregiver approval process was too complicated, took too long or presented unnecessary barriers, especially for whānau caregivers. They went on to say that this could contribute to a lack of stability for tamariki and rangatahi if they were moved into non-whānau care or temporary group home/family homes while the whānau was going through the approval process. However, in one Oranga Tamariki site, we heard how their successful shift towards whānau care was supported by strengths-based needs assessment and referral to services and support from community agencies while the approval process was completed.

Overall, the 2022 Oranga Tamariki caregiver survey showed caregivers were moderately satisfied with most elements of the caregiver approval process. Between 58 to 68 percent of caregivers were satisfied or very satisfied, and between 12 to 24 percent were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with elements of the process. This included the information provided, the time it took for the application to be completed, updates on the progress of applications, training received, and the time it took for caregiver social workers to complete assessments.

The Oranga Tamariki caregiver support policy2 outlines that the policy applies to Oranga Tamariki- approved caregivers (both whānau and non-whānau) and includes provisionally-approved caregivers. However, a third of tamariki and rangatahi are initially placed with unapproved caregivers, and therefore are not able to access supports, such as board payments, until they are at least provisionally approved.

In our chapter on Manaakitanga, we also note that caregivers continue to tell us that they are not receiving sufficient support from Oranga Tamariki, and that financial support is insufficient.

Assessing the safety needs of tamariki and rangatahi when they come into care

Assessing the safety needs of tamariki and rangatahi in care is part of an overall assessment of their needs required under NCS Regulations. The NCS Regulations also require that matters identified in the needs assessment are then taken into account in the development of a plan. It is important that plans address any identified safety issues for tamariki and rangatahi, including situations where they may pose a risk to themselves or others.

Oranga Tamariki self-monitoring data shows that safety needs have been identified and addressed sufficiently well 94 percent of the time3 for those who have a current plan. However, given Oranga Tamariki data shows that only 61 percent of tamariki and rangatahi receive regular and quality engagement from their social workers, it makes it difficult to understand how it can be confident that it almost always sufficiently addresses safety needs in plans. We asked Oranga Tamariki how it can do this if it is not always visiting and seeing tamariki and rangatahi regularly. It advised that visiting and engaging with tamariki and rangatahi was one aspect of understanding their needs. It further explained that needs assessments are informed through all the information it gathers; this includes engagement with parents, significant members of whānau or family, wider whānau or family and family group, (including and where relevant), caregivers, and agencies working with the tamariki or rangatahi and their whānau or family.

While we agree with this, it does not remove the need to see tamariki and rangatahi. It is also not supported by what we heard in our community visits. As set out in our chapter on Whanaungatanga, while connections with whānau appear to be routinely supported by Oranga Tamariki, connections with wider hapū and iwi are not. In our chapter on Rangatiratanga, we report that many whānau and caregivers do not feel listened to by Oranga Tamariki, and our chapters on Kaitiakitanga and Mātauranga highlight that health and education professionals have reported difficulties in collaborating with, and sharing information with, Oranga Tamariki.

Stability of care

Transitions within and out of care

Over three years, the stability of placements has improved. Twenty-five percent of tamariki and rangatahi had a care transition within the year, compared with 48 percent in 2020/2021 and 28 percent in 2021/2022.

While fewer tamariki and rangatahi are experiencing changes in placement, there has been little change in the proportion of planned transitions. Unplanned transitions still account for around half of all changes in placement. Where a transition is planned, there is evidence of sufficient planning 85 percent of the time.

Like last year, whānau continued to speak about structured, planned and gradual transitions to return home as being important. Communication and support from social workers and were spoken about positively. Social worker visits during care transitions, especially when returning home, are essential to monitor the success of the transition, offer support if necessary, and ensure the safety of tamariki and rangatahi in a new placement. However, some social workers supporting family homes said they still observed return home transitions occurring without sufficient support. They told us this led to return home care breaking down, and tamariki and rangatahi cycling back through multiple family homes.

Our recent in-depth review Returning Home from Care looked at the experiences and practices surrounding tamariki and rangatahi cared for at home by their parent/s while in the custody of the State or an approved child and family social service. It found that safeguards and support for tamariki and rangatahi who either remain in, or return to, the care of their parents while in custody are not always there, despite this group being at higher risk of harm than others in care. It also showed that the rates of planning, and visits from social workers in the first week and month were low.

In response to findings from that report, Oranga Tamariki advised that it has updated its “monitoring and reviewing after the return home” guidance to state that the frequency of visiting should be based on the assessed needs of the tamariki or rangatahi and recommends at least weekly visits for the first four weeks.4

Oranga Tamariki data may show that more children are being visited in the first four weeks of returning home. However, as the data is based on a small sample of tamariki and rangatahi, it is not possible to say whether there has been any meaningful improvement compared to last year. Oranga Tamariki casefile analysis shows:

-

that around a third of all care transitions in the sample this year were returns home and just over half of these were planned returns home

-

fifty-eight percent of tamariki and rangatahi in a planned return home and 40 percent of those in an unplanned return home were visited in the first week of their transition home

-

ninety-four percent of tamariki and rangatahi in a planned return home, and 72 percent of those in an unplanned return home, were visited at least once in the first month of their transition home (compared with 75 percent for planned and 63 percent for unplanned last year)

-

thirty-five percent of tamariki and rangatahi who have returned home were visited weekly for the first month or to the planned frequency.

Although care transitions are reducing, there continues to be a shortage of care options

Stable placements can support tamariki and rangatahi to experience healthy relationships, love and belonging, continuity at school and with health services, as well as consistent social connections with whānau and peers. Providing the right support to caregivers is an important part of making a stable home.

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us that finding suitable homes and caregivers can be challenging. A range of options is important, as needs such as living near whānau, with or near siblings, and appropriately skilled caregivers to meet the needs of tamariki and rangatahi can be taken into account.

When there are no other options available, Oranga Tamariki may place tamariki or rangatahi in motel accommodation as a last resort. However, as noted earlier, the number of tamariki and rangatahi staying in motels has reduced, along with the number of nights.

Police told us that they had observed how, in their region, a lack of care options affected decision making, especially for tamariki and rangatahi with complex needs or who required secure placements. For example, a police officer explained that Oranga Tamariki “pressured” Police to find a care option for a child with autism on a temporary care agreement, in a situation where multiple family harm incidents were occurring.

Like last year, Oranga Tamariki social workers and site and regional leadership continued to talk about stable whānau care as the goal if tamariki and rangatahi needed to enter care. At the same time, social workers discussed barriers that delayed, prevented or failed to support stable whānau care, including professional practice, policy and guidance, finance, and work experience and skills.

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi from one site felt that there is a lack of support being provided to whānau caregivers. Some kaimahi told us that whānau are not being supported to take on tamariki and rangatahi. They referred to the caregiver approval process taking months, that whānau are not being provided with funding to obtain legal advice about taking on tamariki and rangatahi, and that whānau are not provided with material items, such as beds, to enable them to take those tamariki and rangatahi in. Kaimahi said the main barrier to supporting whānau caregivers is “money and lack of services”.

We were told that whānau caregivers are not supported once tamariki and rangatahi are in their care, with whānau being asked to “use their own network of support” for respite, and having to pay for things themselves, including elderly whānau. A kaimahi told us, “it’s discriminatory seeing the divide between whānau and non-whānau caregivers”.

Some kaimahi told us that their advice to whānau caregivers is to not take on permanency. They spoke of whānau caregivers ceasing care of high needs tamariki and rangatahi due to a lack of support, with tamariki and rangatahi remaining in Oranga Tamariki care as a result. They told us that once whānau take on custody, support and funding stops, and whānau “have to provide everything”.

In response to hearing about a lack of care options, we asked Oranga Tamariki about its caregiver recruitment policy. Oranga Tamariki advised us that it does not have a policy about the recruitment of non-whānau caregivers. Rather, the care arrangement policy reflects the expectations of legislation and requires that for all tamariki and rangatahi, preference must be given for them to be living with a member of their wider family, whānau, hapū, iwi or family group who is able to meet their needs, including with their siblings where feasible. If an initial care arrangement for te tamaiti or rangatahi is not within their wider family, whānau, hapū, iwi or family group, then Oranga Tamariki practice is to find a care option for them within their wider family, whānau, hapū, iwi or family group at the earliest opportunity. Oranga Tamariki noted that it may be that this practice requirement is leading to less recruitment of non-whānau caregivers at some sites.

Oranga Tamariki further noted it has a policy that prohibits the advertising for caregivers for specific tamariki or rangatahi, but allows advertising for general recruitment.

A lack of information sharing is a barrier to stable care

The NCS Regulations set out what information must be provided to caregivers when tamariki or rangatahi are placed in their care to help meet their needs. This year, Oranga Tamariki data shows that almost half of all caregivers did not get a copy of the plan.

Care partners told us that All About Me plans often arrived blank from Oranga Tamariki and that they often needed to chase Oranga Tamariki to access complete information on the tamariki and rangatahi, including medical assessments, Gateway assessments, psychological reports, Family Group Conference plans and All About Me plans. Care partner kaimahi said this lack of information impacted their ability to support kaimahi and caregivers to care for tamariki and rangatahi.

One leader from a care partner gave an example of how good it was when they did receive full information during a transition between placements:

“We had a girl come in – she had her whole care plan and her whole All About Me plan done – she could express her anxieties and her triggers and that worked really well. We were able to share that with our residential staff. We don’t get that very often.”

Several Oranga Tamariki kaimahi also gave examples where information sharing was a barrier within Oranga Tamariki. Kaimahi from a group home said the All About Me plans they received did not always match up with the rangatahi, and that they do not always receive timely responses from social workers when asking for supplementary information. One kaimahi had access to CYRAS and could look up case information directly, but other kaimahi did not have access, and this was a barrier to meeting the needs of the rangatahi. In addition, Oranga Tamariki team members supporting family homes in another region said All About Me plans often “weren’t good” and they “have to go into CYRAS and make sure information is all there for caregivers to create a stable placement”.

Social workers talked about how the All About Me plan was needed, even for short-term respite or emergency care, but they gave varying opinions about how: fit for purpose or easy to use CYRAS is; the benefit and ease of use of the Tuituia needs assessment tool; how much information it was appropriate to share (for example with respite caregivers); the completeness and currency of All About Me plans; and how to approach getting information from tamariki and rangatahi to update needs assessments and plans. When discussing the importance of plans and keeping them updated, one senior practitioner from within Oranga Tamariki told us: “you could probably do that more subtly if you visited more regularly”.

Lack of information sharing and the impact of this for caregivers meeting the needs of the tamariki and rangatahi in their care was a key insight in our 2021/22 report, and it remains an issue this year.

Experiences of respite continue to be mixed

A few caregivers mentioned lack of access to suitable respite. We heard of whānau caregivers being told by their Oranga Tamariki social workers to find other whānau members, or to use their own networks of support for respite, but that Oranga Tamariki was unwilling to pay whānau members to provide respite care on the same basis it would pay non-whānau respite caregivers.

Oranga Tamariki national office advised us that all caregivers are entitled to 20 days respite per year, and that during this time, the primary and respite caregivers receive Foster Care Allowance. It noted it was unclear how the situation in the above example could have occurred, given the policy, however, we have noted several examples in this report where frontline practices and understanding does not align with Oranga Tamariki policy.

There were mixed experiences of accessing respite, with some caregivers having sufficient access to respite through Oranga Tamariki, Open Home Foundation or an NGO care partner, whereas others said they were accessing respite, but had needed to ‘fight for it ‘– or they used informal respite arrangements. Some caregivers implied the onus was on them (rather than social workers) to find respite caregivers.

In the 2022 caregiver survey, 39 percent of Oranga Tamariki caregivers used respite within the last 12 months. Among the 61 percent of caregivers who did not use respite, the major reasons were not needing respite for this child (41 percent) or that it would be too traumatic for the child (19 percent). There was also a reduction in the number of caregivers reporting that they did not know they could access respite, from 13 percent in 2021, to six percent in 2022.

Across most measures this year, the Open Home Foundation compliance remained consistent. There are a few areas where improvement was noted; in relation to reviewing and plans following an allegation of abuse, and in preparing plans for care transitions. There were also a few

areas where compliance has deteriorated; notably around recording and reporting information in relation to allegations of abuse in a consistent manner, providing support following an allegation of abuse, and reviewing foster parent support plans following an allegation of abuse.

Allegations of abuse and neglect

In reading the data, it is important to acknowledge that there were twelve cases in total, and therefore non-compliance on one case can have a significant impact on the percentage.

73% - 2021/2022

75% - 2022/2023

91% - 2021/2022

38% - 2022/2023

82% - 2021/2022

88% - 2022/2023

78% - 2021/2022

75% - 2022/2023

55% - 2021/2022

88% - 2022/2023

91% - 2021/2022

75% - 2022/2023

64% - 2021/2022

50% - 2022/2023

Other aspects of Aroha

61% - 2021/2022

60% - 2022/2023

96% - 2021/2022

96% - 2022/2023

85% - 2021/2022

81% - 2022/2023

87% - 2021/2022

87% - 2022/2023

39% - 2021/2022

73% - 2022/2023

Safety

This year Open Home Foundation reported 12 allegations of abuse for or in Open Home Foundation custody. This is slightly fewer than last year, when 15 allegations were reported. All 12 allegations were responded to within the reporting period, and for eight of the allegations, a report of concern was made within 24 hours. Policy requires that a report of concern is made for all allegations of abuse. In one instance, following a discussion with the local Oranga Tamariki site, and on the direction from that site, it was agreed that a report of concern would not be made.

Open Home Foundation has reported to us that it has identified some incidences where it could improve the way it records information of an allegation of abuse. Open Home Foundation advised that it aims to continue to run mentoring sessions with its team, and to provide refresher training in identifying abuse to all Open Home Foundation social workers. One Open Home Foundation kaimahi told us:

“The children tell them things – told them stuff and put in a ROC [report of concern] – spoke to grandad – very casual conversation with tamariki – the foster parent was pulling her hair out – then they go back and see grandad and see more family violence.”

Social Worker visits with tamariki and rangatahi

Open Home Foundation visited tamariki and rangatahi in their custody to the planned frequency 60 percent of the time, which is consistent with 2021/2022. Open Home Foundation policy is for at least one visit per month. When comparing the absolute frequency of social worker visits, 95 percent of tamariki and rangatahi in Open Home Foundation custody were visited at least once every eight weeks during 2022/2023, which is an increase from 90 percent last year.

When talking about support for return home transitions, communication and support from Open Home Foundation social workers was discussed positively in our community visits.

Assessing caregivers and their households

Eighty-one percent of Open Home Foundation foster parents and carers were assessed before children were placed with them, which is a small decrease from 85 percent in 2021/22. This year, of the eight cases where foster parents/whānau carers were not fully approved, two were ‘closely monitored’ until the assessment was completed, five received ‘some monitoring’ and one received ‘no monitoring’.

1 We will be looking at the quality and accuracy of decision making for all reports of concern, (whether the are in care on not) as part of our review of recommendations made by Dame Karen Poutasi in her report Ensuring strong and effective safety nets to prevent abuse of children (https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/Reviews-and-Inquiries/System-review-Dame-Karen-Poutasi/Final-report-Joint-Review-into- the-Childrens-Sector.pdf)

2 https://practice.orangatamariki.govt.nz/policy/caregiver-support/

3 Those for whom safety needs were ‘not applicable’ were excluded from this measure.

4 https://practice.orangatamariki.govt.nz/previous-practice-centre/policy/caring-for-children-and-young-people/key- information/returning-mokopuna-safely-home/