Response to the Poutasi review

The review found five critical gaps as follows:

- the needs of a dependent child when charging and prosecuting sole parents through the court system are not formally identified

- the process for assessing the risk of harm to a child is too narrow and one-dimensional

- agencies and services do not proactively share information, despite enabling provisions

- there is a lack of reporting of risk of abuse by some professionals and services

- the system’s settings enabled Malachi to be unseen at key moments when he needed to be visible.

The findings were reported in December 2022, and echoed similar themes from previous child death reviews in New Zealand. Similar themes included a need for greater collaboration across agencies, better information sharing, and the need to build awareness and knowledge to better inform identification and reporting of child abuse at both a community and professional level.

At the time the Poutasi review was published, the Government accepted nine of the recommendations and committed to considering the remaining five5. A November 2022 Cabinet paper6 noted that the recommendations could be categorised as:

- operational, or within the authority of Chief Executives to support and progress (recommendations 3, 4, 5, 7 and 13)

- requiring Ministerial and Cabinet approval and subsequent legislative amendments (recommendations 10, 11 and 12)

- subject to further consideration because of significant consequences that could arise from implementation (recommendations 1, 2, 6, 8 and 9).

The Cabinet paper invited the Minister for Children or other relevant Ministers to report back to Cabinet in 2023 on the recommendations that require Cabinet approval.

The subsequent 2023 report to Cabinet [CAB 23 MIN 0398 refers]7 noted that eight of the 13 recommendations were more substantive because they involve a range of complexities, and/or may lead to significant change in the children’s system. Oranga

established four across-agency working groups in early 2023 to prepare advice on these recommendations including:

- vetting and supporting caregivers (recommendations one, two and six)

- information sharing (recommendation seven)

- mandatory reporting (recommendations eight and nine)

- the children’s system (recommendations 11 and 12).

Oranga Tamariki is also working with lead and supporting agencies to consider or progress the remaining five recommendations.

Although not all recommendations were accepted, the 2023 Cabinet paper directed agencies to continue to prioritise progressing each of the recommendations outlined in the Poutasi review, to ensure that the children’s system responds with the speed and urgency required.

Oranga Tamariki co-ordinates updates on this work for the Minister for Children every six months. These updates are published on its website here: https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/about-us/performance-and-monitoring/ reviews-and-inquiries/malachi-subecz-system-review/.

At the time of writing, none of the recommendations made by the Poutasi review had been fully implemented, although there was evidence of detailed planning underway in respect of most of the recommendations.

When we spoke with Oranga Tamariki national office, they told us that “work has not moved as quickly as Oranga Tamariki would have liked. An election and a change of government have impacted decision making processes”. Oranga Tamariki also said that there is “significant complexity” behind some of the recommendations, which may appear straightforward, but have several potential unintended implications that require complex consideration and assessment before making policy decisions. Oranga Tamariki national office told us how important it is to get ministerial support across portfolios to achieve progress. In response to our information request, all agencies mentioned the need to get policy decisions in order for them to implement change.

The needs of a dependent child when charging and prosecuting sole parents through the court system are not formally identified

The Poutasi review identified that of imprisoned sole caregivers can be in the care of another person without formal authority. This can be for long periods, without consideration for the child’s safety or wellbeing. It notes that tamariki of people in prison are among our most vulnerable citizens. An imprisoned parent has very little real ability to check up on a child’s care, or to follow up on a caregiver’s ongoing suitability or treatment of the tamariki.

The Poutasi review found that when a sole parent is facing a custodial sentence it should be a red flag for risk.

Recommendation one

Oranga Tamariki should be engaged in vetting a carer when a sole parent of a child is arrested and/or taken into custody. NZ Police (or other prosecuting agency) in the first instance, and the Court in the second, will need to build into their processes time for this to occur.

Recommendation two

Oranga Tamariki should be engaged in regular follow-up checks and support for such an approved carer while the sole parent remains in custody. Resourcing must be addressed to enable this to occur.

The lead agency for both recommendation one and recommendation two is Oranga Tamariki, supported by the Department of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, and the NZ Police.

These recommendations were noted by Cabinet in 2022 as being subject to further advice because significant consequences could arise from implementation. Legislative change would be required.

Status: Not achievedThere has been little progress in vetting carers

NZ Police advised that its People in Police Custody policy already includes a section on “detainees with the responsibility for children or young persons”. In relation to Malachi, NZ Police advised that as Malachi’s mother had made arrangements for Malachi’s care, there was no further role for the NZ Police in this instance8.

Policy discussions over the past 14 months have focused on the appropriateness of vetting a carer chosen by the guardian of the child, and what happens if the checks produce information of concern. Work has also included consideration of whether follow up checks are required and what types of support are available for tamariki, caregivers, parent(s) in prison, and . We were advised that this work is significant and complex and, depending on the approach taken, could take several years to progress.

We were told that agencies have engaged with whānau care partners, national care providers, members of the judiciary and the legal profession, young people with care experience and/or who have had a parent in prison, Pillars Ka Pou Whakahou (an organisation that supports tamariki and whānau who have a parent in prison) and caregivers of tamariki in and outside of state care. The purpose of the engagement was both to help inform the response, as well as to determine whether recommendations one and two should be implemented. What it highlighted is that there are a range of views on whether and how to implement these recommendations.

To fix a problem it is important to first understand the extent of it, however this remains unknown and progress to understand the number of carers in scope is slow.

We asked the Ministry of Justice how many times a sole parent or caregiver has been before the District Court on charges that could lead to a sentence of imprisonment since the review. The Ministry of Justice advised it could not provide this information because it is not recorded and there are no plans to change or update the case management system to record this.

The Department of Corrections was not able to tell us how many times a pre-sentencing report had been required for a sole parent requiring care for their tamariki since the review, or about any reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki as a result. It does not differentiate reports by whether they are for a sole parent. However, Corrections advised that the week before providing its response to us it made changes to its technology, which will enable it to record and report this information in future.

From our perspective efforts could have been made to understand the size of this issue. For example, as a first step Corrections could have sampled the current women’s prison population to understand how many have children, and of those how many are satisfied with their children’s care arrangements. The women’s prison population is smaller than the men’s prison population, so this would provide a starting point. Steps could then be taken to also understand this across the men’s prison population to give an indication of the overall size of the issue.

We also asked the Ministry of Justice for an update on any process changes for sentencing of sole parents or caregivers. It told us that in late 2022 Judge John Walker formed the Primary Caregivers in Custody with Dependent Children working group. This cross-agency working group comprises members of the judiciary, the Ministry of Justice, the Department of Corrections, NZ Police, Oranga Tamariki, Public Defence Service, Crown Law, and the New Zealand Law Society.

Although not a direct response to the recommendations of the Poutasi review, the working group operates in parallel, and has identified several opportunities where, with consent from the defendant, judges can be made aware of the existence of dependent children. This could provide an additional opportunity to check on tamariki. As of February 2024, the Public Defence Service, Legal Aid Service and NZ Police had either updated or were in the process of updating forms to include a field asking about the existence of dependent children.

Agencies advise further analysis and policy decisions are required to progress recommendations one and two.

What we’ll look for in another 12 months on critical gap one

When we next review progress we will be looking at whether, and how, agencies are routinely identifying and responding to the needs of dependent tamariki whose parent(s)/guardian(s) are arrested and/or taken into custody. This will include looking at the data that the Department of Corrections has recently started to collect, and how it is being used to keep tamariki safe.

The process for assessing the risk of harm to a child is too narrow and one-dimensional

The Poutasi review found that at various points, the views of other agencies, as well as those of Malachi’s and community, should have been sought or shared by agencies so they could be considered in assessing and responding to Malachi’s needs. This may have resulted in a decision by Oranga Tamariki to go and see Malachi.

Recommendation three

Multi-agency teams working in communities in partnership with and , resourced and supported throughout the country to prevent and respond to harm. There are examples of this happening already across the country. Implementation in all localities must be a priority so that relevant local teams can help assess, respond to the risk to a child, and provide support.

The lead agency for recommendation three is Oranga Tamariki, supported by NZ Police, Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Health, Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora, and Te Puna Aonui9.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as already being implemented. It is operational in nature or within the authority of Chief Executives to progress.

Status: Not achievedMulti-agency teams are not in place in all communities

Multi-agency teams as described in this recommendation are not in place in every community. Examples of existing or emerging multi-agency programmes are listed below. While it is important to have models of practice that fit individual communities, it is not yet known what the collective impact of these different models is having on child safety.

- Te Aorerekura – National Strategy and Cross Agency Action Plan to Eliminate Family Violence and Sexual Violence, hosted by Te Puna Aonui. Te Puna Aonui works in partnership with specialist sector, communities and iwi to systematically look at ways to improve coordination and enable a collective response to family and sexual violence.

- The Integrated Community Response (ICR) Programme is an essential part of delivering on Te Aorerekura and has supported localities to grow their infrastructure, capacity, and capability to run local multi-agency tables and responses. So far the ICR programme has supported eight locations with funding, advice and a co-learning support network. Further roll out will continue.

- The Integrated Safety Response (ISR), hosted by NZ Police on behalf of Te Puna Aonui and Whāngaia Ngā Pā Harakeke, a partnership between NZ Police and local iwi Māori to respond to family harm, which are initiatives that reflect collaboration and collective responsibility that work to prevent and respond to harm.

- The Enabling Communities programme delivered under the Oranga Tamariki Future Direction Plan, which is working to restore and empower iwi and communities to lead the prevention of harm for , and whānau.

NZ Police advised us that it has a network of Māori, Pasifika and ethnic teams across the country working in partnership with communities to address issues as they arise. NZ Police further advised that its Child Protection Teams work in partnership with partner agencies when responding to harm, with the Child Protection Protocol (CPP) as an example.

Recommendation four

Medical records held in different parts of the health sector should be linked to enable health professionals to view a complete picture of a child’s medical history.

The lead agency for recommendation four is Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as already being implemented. It is operational in nature or within the authority of Chief Executives to progress.

Status: Not achieved

Linking of medical records is expected in 2026

Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora advised that the Hira programme10 will give approved whānau and health providers a comprehensive view of a child’s medical history and health system interactions. The new system will help health providers to monitor wellbeing indicators over time, regardless of where healthcare is accessed. It will give them secure, easy access to a child’s ‘real time’ information when needed. This is still some years away.

Health NZ advised us that Hira is on track to have patient summaries available to individuals and their healthcare providers via My Health Record by mid-2024. While this technology will enable individuals, families, and whānau to view their information, including community dispensed medicines, vaccination status, entitlements (initially Community Services Card and High Use Health Card), laboratory results (initially Covid-19), and other data (for example allergies and conditions), it does not provide the linking of medical records recommended in the Poutasi review.

Work is also underway to provide a single national approach for sharing health information between authorised healthcare providers. This will enable consistent nationwide access to a child’s primary care medical records. In her review, Dame Karen Poutasi noted:

“Medical records should be joined up, and whilst there are current health data and digital initiatives to do so, these should be expedited. Emergency departments, hospital, primary care and preschool Well Child Check records should be linked to facilitate the opportunity to detect child abuse and neglect. Malachi was seen at a health centre while he was carrying signs of abuse (albeit these were not visible through his clothes) and had experienced significant weight loss since his last Well Child Check”.

Development of a business case began in early 2021, before the recommendations of the Poutasi review. However, funding is only confirmed to complete tranche one of the business case by the end of June 2024. In order to complete tranches two and three, which will deliver on the intent of recommendation four, further funding will need to be approved. Assuming funding is confirmed, this work is then not expected to be implemented before 2026. It has not been expedited as recommended by the Poutasi review.

Recommendation five

The health sector should be added as a partner to the Child Protection Protocol between NZ Police and Oranga Tamariki to enable access to health professionals experienced in the identification of child abuse, and to facilitate regular joint training.

The lead agencies for recommendation five are the Ministry of Health and Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora, supported by Oranga Tamariki and the NZ Police.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as supported in principle. It is operational in nature or within the authority of Chief Executives to progress.

Status: Not achieved

No decision has been reached on health involvement in the Child Protection Protocol

The Child Protection Protocol (CPP) is the agreement between NZ Police and Oranga Tamariki to work together where abuse or neglect is suspected. A regular review of the CPP that is currently underway has included targeted engagement with NZ Police and Oranga Tamariki kaimahi. This has provided information about the strengths and opportunities for improving the CPP, including experiences of accessing health expertise in child protection matters. It revealed that agencies felt able to access paediatric assessments and advice in urgent circumstances and when working under the CPP. Issues were identified with delays, and challenges at times accessing follow-up support.

The Poutasi review also identifies that the CPP requires joint annual training between Oranga Tamariki and NZ Police. Police told us that the existing training for Police investigators is supported by health providers. If Health were added to the CPP and all three agencies were to regularly train together, this could more formally ensure a shared understanding of how to draw on each other’s strengths when responding to reports of concern about abuse of children.

We were advised that the review of the CPP is ongoing with an interim decision on how the health sector can be involved yet to be made. Options include full operational membership of the CPP, partial membership in areas such as governance, participation in review and training, and not joining in lieu of other measures that would support access to health expertise and services in the context of the CPP. Decisions are expected to be made by Chief Executives.

What we’ll look for in another 12 months on critical gap two

When we next review progress we will be looking for evidence that a more holistic approach to assessing risk to tamariki has been implemented across the children’s system, and to understand whether and what difference this is making for tamariki and their whānau.

Agencies and services do not proactively share information, despite enabling provisions

The Poutasi review found that there was an urgent need to consolidate a whole picture of the risks for Malachi. Each agency had part of Malachi’s reality, but none registered the red flags to bring it to each other.

The Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 already allows agencies and persons considered to be “child welfare and protection agencies, and independent persons” under the Act to share information to prevent or reduce the risk of harm to a child, or to assess risk. However, agencies and their services did not proactively share information.

Recommendation six

The Ministry of Social Development should notify Oranga Tamariki when a caregiver who is not a lawful guardian, and who has not been reviewed by Oranga Tamariki or authorised through the Family Court, requests a sole parent benefit or other assistance, including emergency housing support, for a child whose caregiver is in prison.

The lead agencies for recommendation six are Oranga Tamariki and the Ministry of Social Development, supported by the Department of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, and the NZ Police.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as subject to further advice because significant consequences could arise from implementation. Legislative change would be required.

Status: Not achieved

Progress on recommendation six will first require decisions on recommendations one and two

Agencies advise that implementation of this recommendation is contingent on the policy decisions that are yet to be made in respect of recommendations one and two.

The Ministry of Social Development told us it can (and does) tell Oranga Tamariki when it considers to be in need of care and protection, and the law provides for this. However, application for a sole parent benefit, in itself, is not sufficient grounds to notify Oranga Tamariki. Therefore, it would need to have a clear purpose for sharing information, which may be provided through policy decisions in respect of recommendations one and two.

No change or progress has been made towards recommendation six.

Recommendation seven

The enhancement of understanding of the information sharing regime in the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, to educate and encourage child welfare and protection agencies and individuals in the sector to share information with other child welfare and protection agencies on an ongoing basis.

The lead agencies for recommendation seven are Oranga Tamariki, the Department of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, NZ Police, Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Health, Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora, and the Ministry of Education (the Information Sharing Working Group).

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as supported in principle. It is operational in nature or within the authority of Chief Executives to progress.

Status: Not achieved

Information sharing between agencies remains an issue

We know that reports of concern from government agencies to Oranga Tamariki are already high, and this is a form of information sharing. Of the approximately 80,000 reports of concern received annually across all notifier types, around 20,000, or a quarter of these are made by the NZ Police11. In addition, health agencies and schools make around a further 10,000 reports respectively each year. However, we also know that not all of these reports are progressed for further action by Oranga Tamariki. This raises two questions. First, is the level of reporting enough? Improved education and training across the sector could help provide confidence in this regard. We discuss this further under critical gap four. Second, is Oranga Tamariki making the right decision on which cases require them to engage with tamariki and their to assess their safety? We address this question later in our report.

However, we also know from our ongoing monitoring that information sharing between agencies is a problem more broadly. Agencies advise the legal basis to share information is not at issue, but rather it is a lack of clarity at the frontline. All agencies leading the response to recommendation seven are child welfare and protection agencies that are able to share information under section 66C of the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, to support the safety and wellbeing of tamariki and .

The Information Sharing Working Group has agreed to, but not yet implemented, a range of actions to ensure frontline staff at relevant agencies understand and use the information sharing provisions through:

- delivering updated information sharing guidance, communication, and other resources to frontline staff so that there is shared advice and clear understanding about information sharing. For example, ongoing learning and development opportunities for professional groups

- highlighting information sharing work in regional leadership meetings that reach a range of stakeholders, convened by Regional Public Service Commissioners. Oranga Tamariki is working with the Regional Public Service office to support this action by providing communications through their regular newsletter, attending monthly , and linking resources.

In addition, in March 2024, the Government Chief Privacy Officer released guidance on the development of information sharing agreements. This guidance could support an improved understanding by agencies of how to share information to better protect tamariki.

What we’ll look for in another 12 months on critical gap three

When we next review progress we will look to see how information is shared between agencies at the frontline, and whether and what difference this is making to improve the safety of tamariki. This is also something that we consider as part of our annual reporting on compliance with the National Care Standards.

There is a lack of reporting of the risk of abuse by some professionals and services

The Poutasi review noted that the childcare centre Malachi attended had a policy requiring the reporting of child abuse, but they did not follow this despite having and documenting concerns for him. The review further noted that across professional groups the reporting and feedback process is not well understood and it is therefore likely that harm and abuse is under-reported.

Recommendation eight

Professionals who work with children should be mandated to report suspected abuse to Oranga Tamariki. This should be legislated by defining the professionals and service providers who are to be classed as ‘mandatory reporters’, to remove any uncertainty around their obligations to report.

Recommendation nine

The introduction of mandatory reporting should be supported by a package approach that includes:

- a mandatory reporting guide with a clear definition of the red flags that make up a high-risk Report of Concern, together with the creation of a ‘High Report of Concern’ category similar to New South Wales ‘Risk of Significant Harm’ definition

- defining mandatory reporters, all of whom should receive regular training

- in addition, for professionals deemed to be mandatory reporters, there should be:

- undergraduate courses teaching risks and signs of child abuse

- mandatory regular updated training regarding their responsibilities and the detection of child abuse, with practising certificates conditional on training and refreshers.

The lead agency for both recommendation eight and recommendation nine is Oranga Tamariki, supported by the Department of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, NZ Police, Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Health, Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora, Te Aka Whai Ora, the Ministry of Education and the Education Review Office (the Mandatory Reporting and Training Working Group).

These recommendations were noted by Cabinet in 2022 as subject to further advice because significant consequences could arise from implementation. Legislative change would be required.

Status: Not Achieved

It is not clear what impact mandatory reporting would have in New Zealand

Introduction of mandatory reporting would require legislative change. The Mandatory Reporting Working Group undertook targeted engagement from July to September 2023. The engagement tested initial responses to the recommendations in the Poutasi review. It sought to identify what a mandatory reporting regime could look like and identify other options to support professionals to recognise and respond to abuse.

Oranga Tamariki advised that there are strong views both for and against mandatory reporting, with limited consistency in those views within and across sectors. Feedback to date indicates that a broad and systemwide response is required to raise awareness and respond to child abuse. Mandatory reporting, if pursued, must be only one part of a broader national strategy.

We have heard of concerns about what mandatory reporting may mean. They include potential over-surveillance of Māori and Pacific and . We also heard that it could risk over-reporting. The Poutasi review considered these risks, and recommended that if implemented, mandatory reporting should be supported by regular training and a mandatory reporting guide as ways to mitigate the risks.

While the response from Oranga Tamariki shows significant thought has gone into considering recommendation eight, there is little detail on the response to recommendation nine around training and what to look for when determining whether to make a report of concern.

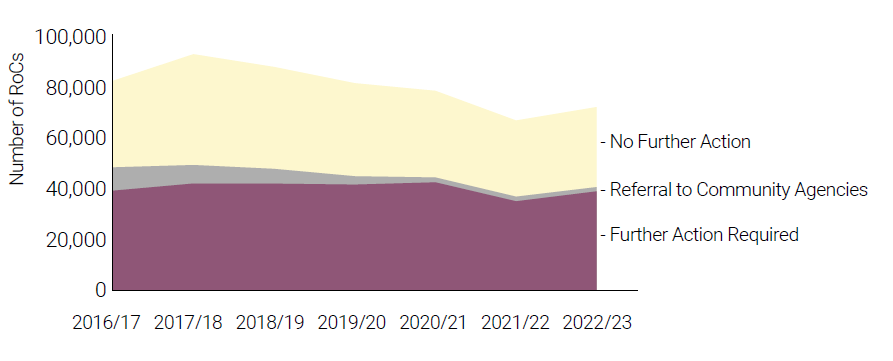

To help us put this work in context, we asked Oranga Tamariki to provide data on reports of concern it received, by notifier type, from across financial years from 2016/2017 to 2022/2023. The data shows that since 2016/2017, around 80,000 reports of concern have been received each year for around 58,000 tamariki. This equates to reports of concern for approximately 5 percent of the current child and youth population, with 1.2 million people aged 18 and under in Aotearoa12.

Graph 1: Annual Reports of Concern and Oranga Tamariki response

While there is variation in the number of reports of concern, consistently around 40,000 per year result in further investigation.

Graph 1: Annual Reports of Concern and Oranga Tamariki response

Reporting had been decreasing since 2017/18, with the lowest number of reports made during 2021/22. In 2022/23 the number of reports increased again towards the reporting numbers seen before the Covid-19 pandemic. Across this time, regardless of changes in reporting frequency, the number of cases that Oranga Tamariki progresses to assessment or investigation (where the child should be sighted) remains largely the same. Each year from 2016/17 to 2022/23, around 40,000 reports of concern were progressed to an assessment or investigation13.

Recent analysis by Oranga Tamariki14 shows that the largest decreases in the numbers of reports of concern made to Oranga Tamariki are those from professional/government notifiers. Although the analysis cannot pinpoint why this is, it does not attribute it to a reduction in need. However, it notes that a reduction in child poverty rates may have improved wellbeing of tamariki. The Oranga Tamariki report noted that decreasing trust among some professionals that Oranga Tamariki will respond, and long response times at the National Contact Centre, were contributing to the decrease in reports of concern being made. This is a further challenge to overcome to improve reporting of child protection concerns.

While undertaking this review, we spoke with officials in Australia, to better understand the experiences with mandatory reporting there. At the time of the Poutasi review, New South Wales Child Protection Services had recently introduced mandatory reporting and this was held up as a success. When we spoke with officials in New South Wales we heard that things have changed since then. While reports of concern initially decreased after the introduction of mandatory reporting, they have subsequently increased year on year, to the point where officials describe themselves as “drowning”. They told us they have too many reports of concern coming in the door that do not require a statutory response and this is placing pressure on their resources and making it harder to see the “wood for the trees”.

Similarly, in Victoria which also has mandatory reporting, we heard that their Child Protection Services have a similar challenge in managing workloads.

We heard that Oranga Tamariki is already struggling to address the number of reports of concern it receives. In the context of the recommendation to introduce mandatory reporting, this leaves two apparent options:

- further resource/reprioritise existing funding within Oranga Tamariki (as well as take opportunities to streamline processes and remove duplication) along with improved funding for community organisations, and/or

- improve education and training for professionals and service providers around the identification and reporting of child abuse.

Recommendation 10

There should be active monitoring of implementation by early childhood education services of their required child protection policies to ensure they are providing effective protection for children. Therefore, the Ministry of Education and the Education Review Office should jointly design and administer a monitoring and review cycle for the implementation of child protection policies in Early Learning Services.

The lead agency for recommendation 10 is the Ministry of Education, supported by the Education Review Office.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as accepted in principle, subject to Cabinet decisions and with further advice to be provided. It requires Ministerial and Cabinet approval and subsequent legislative amendments.

Status: Not achieved

Early learning services are already required to have child protection policies, and ERO check for this

The Ministry of Education confirmed that early learning services are required to have a written child protection policy that meets the requirements of the Children’s Act 2014 when applying for a licence, and again when moving from a probationary licence to a full licence.

Early learning services are also required by the Ministry of Education to review their child protection policies every three years and the Education Review Office (ERO) checks compliance on a three-yearly cycle. This includes looking at how early learning services manage areas such as emotional and physical safety which have a potentially high impact on tamariki wellbeing.

There are working protocols in place that outline how ERO and the Ministry of Education work together when likely non-compliance is identified. Any shortfalls in compliance with child protection requirements are a serious risk and are escalated for a response by the Ministry of Education’s front-line licensing teams.

ERO provided recent data on non-compliance in relation to child protection identified in early learning services in relation to:

- whether early learning services have a procedure for safety checking all children’s workers, compliant with the Children’s Act 2014

- whether early learning services have a written child protection policy which is compliant with the Children’s Act 2014.

The data from ERO shows that it is identifying a slight increase in instances of non- compliance with these legislative requirements in early learning services. In the six months between July and December 2023, it found 108 instances of non-compliance with safety checking children’s workers and home-based service families, and 17 instances where a centre did not have a written child protection policy compliant with the Children’s Act. This compares with 160 and 40 non compliances respectively for the 12 months from July 2022 to June 2023. This suggests that some services do not have a comprehensive understanding of the requirements of a robust child protection policy. ERO also told us that its staff have all undertaken recent professional learning with a focus on safeguarding children, which has heightened awareness of these areas when evaluating early learning services.

Reports of concern from Early Childhood Education providers have increased, however barriers to reporting remain

While monitoring compliance of child protection polices is important, it is arguably more important that early learning services know when and how to raise concerns.

When we spoke with Oranga Tamariki kaimahi about any change in reporting practices from Early Childhood Education (ECE) providers, they said that the Poutasi and agency reviews have affected the attitudes of some ECE providers and other organisations, making some overly cautious and reactive, while others take a long time to report allegations of abuse or neglect.

We heard that some Oranga Tamariki sites are proactively engaging with and providing training to support ECE providers understanding of abuse and when to report concerns to Oranga Tamariki.

“I’m starting to make good connections; they call and ask for advice and information.” – site kaimahi

Some kaimahi talked about working with Child Matters to provide training for local ECE providers on child protection. While this is not the responsibility of Oranga Tamariki, we heard it has helped improve the quality of reports of concern received from ECE providers. However, we heard that attendance is based on ECE staffing capacity, with only some sessions having a good number of attendees.

“The willingness is there but their staff are stretched too.” - site leadership

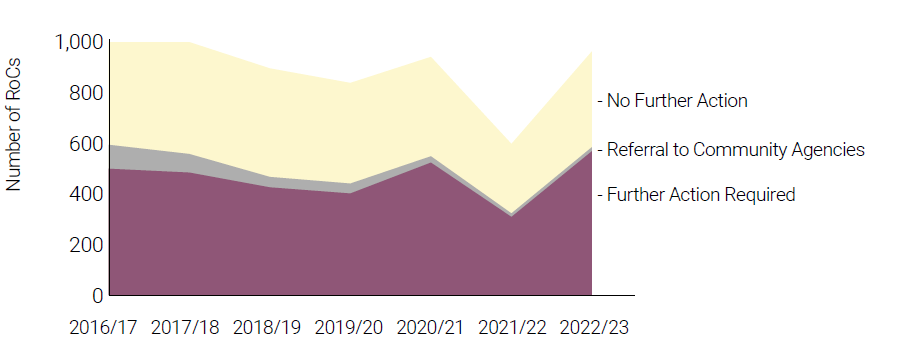

Despite these concerns, the number of reports of concern from the ECE sector has increased since Malachi died.

Data from Oranga Tamariki shows that the numbers of reports of concern from ECE providers were at their lowest at the time of Malachi’s death in 2021/22 and have since increased towards the numbers seen in 2016/17. The proportion of reports where further action is taken remains largely the same, irrespective of the number of reports.

Graph 2: Annual reports of concern from the early childhood education sector and the Oranga Tamariki response

The proportion of reports where further action is taken remains steady, irrespective of the number of reports.

Graph 2: Annual reports of concern from the early childhood education sector and the Oranga Tamariki response

The Ministry of Education and ERO have taken steps to understand barriers to reporting, but work to address these barriers is still to be done

As a first step to understand this better, the Ministry of Education and ERO sought feedback from the ECE sector throughout 2023. This included teachers, service owners, and internal staff and helped both agencies understanding of the barriers to effective implementation of child protection policies. For example, there was consensus from the ECE sector that it would be helpful to understand the roles of the Ministry of Education, ERO and Oranga Tamariki in child protection, along with training as part of their qualification, and more practical information on how to talk with parents about their concerns and managing these difficult conversations.

In addition, the Ministry of Education and ERO have subsequently developed a work plan. This includes a strengthened review cycle and a range of other actions to enhance and support child protection in ECE. The work plan is subject to final approval and resourcing decisions which will be confirmed once the Ministry of Education has finalised its savings programme. Some of the recommended changes to strengthen the review cycle are also dependent on regulatory setting change. The Government has announced its intention to carry out an ECE regulation sector review this year, which may impact on this work.

The Ministry of Education and ERO advise that, while developing the work programme, they have:

- publicised the Ministry of Education’s child protection training module to the sector through different channels and networks, including the Ministry of Education’s He Pānui Kōhungahunga | Early Learning Bulletin, leading to an 85% increase in the number of people completing the module in 2023 (7,291 people)

- promoted and supported greater awareness about how to report child protection and safety concerns, along with developing and sharing a clearer understanding of the roles and responsibilities of key agencies in this.

The Ministry of Education and ERO advise they will continue raising awareness of the training module and how to report concerns as other work progresses in 2024.

We asked Oranga Tamariki national office if it had a national plan or strategy for working with ECE providers on policies, practice, and when to report concerns, or if it had given any advice to sites on working with ECE providers.

National office kaimahi told us that this was not something that had been identified as part of its work plan and that they were not aware of a consistent approach to working with ECE providers around the country. We were told that engagement with ECE providers was not something that had been identified as a key prevention mechanism.

What we’ll look for in another 12 months on critical gap four

When we next review progress against the recommendations, we will look for evidence of how children’s agencies are working together to identify cases that need to be referred to Oranga Tamariki. This will include how agencies are working together to proactively respond to whānau to prevent needs escalating to require a statutory response. We will also look for progress on the proposed regulatory changes by the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Regulation, and the impact this has on reviews undertaken by ERO. In particular, if reviews undertaken by ERO show reduced issues with compliance related to child protection.

The system’s settings enabled Malachi to be unseen at key moments when he needed to be visible

The Poutasi review found that the system settings allowed Malachi to be invisible. He did not have a voice and was not seen or focused on by professionals working within the children’s system. It notes that there were those who tried to act but were not listened to, those who were uncertain and did not act, and those who knew and chose not to act.

Recommendation 11

The agencies that make up the formal Government’s children’s system should be specifically defined in legislation.

Recommendation 12

These agencies should have a specific responsibility included in their founding legislation to make clear that they share responsibility for checking the safety of children.

The lead agency for both recommendations 11 and 12 is Oranga Tamariki, supported by the Department of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, NZ Police, Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Health, Health NZ – Te Whatu Ora, and the Ministry of Education (the Children’s System Working Group).

These recommendations were noted by Cabinet in 2022 as accepted in principle, subject to Cabinet decisions and with further advice to be provided. They require Ministerial and Cabinet approval and subsequent legislative amendments.

Status: Not achieved

Responsibilities of children’s system agencies are clear, but may not be being routinely implemented

We were advised that the Children’s System Working Group produced a report clarifying the existing children’s system in New Zealand, including statutory accountabilities relating to child wellbeing and protection. It concluded that the existing formal children’s system has a range of opportunities to improve child safety, including:

- reviewing the membership of the formal children’s system, including children’s agencies, agencies required to have child protection policies, agencies required to conduct safety checks of children’s workers, and child welfare and protection agencies

- strengthening cross-agency practice of how these statutory obligations, particularly child protection policies, are implemented

- exploring options for what a cross-system responsibility to check on the safety of children could look like in practice (and the corresponding legislative options)

- strengthening practice in how the system provides early intervention support to children and young people before the point of involvement with Oranga Tamariki.

The Children’s System Working Group is now preparing a report on potential activities to address the identified gaps in the children’s system to better prevent, recognise, report and respond to child abuse.

Under the Children’s Act 2014, agencies that deliver children’s services have a range of statutory accountabilities to ensure, support and improve the safety and wellbeing of . In particular, prescribed agencies are required to have a child protection policy. A child protection policy is a document describing the process that the organisation uses to identify and report child abuse.

Under the legislation, these child protection policies must be available on agencies’ websites and must be reviewed every three years.

We were interested in whether and how children’s agencies are meeting their statutory responsibilities to identify and report child abuse. To this end we asked the agencies we reviewed if they have a current child protection policy that is compliant with the Children’s Act. Only two of the agencies we reviewed have a current child protection policy. The other agencies advised that their policies are currently under review, despite planned reviews being overdue, in some cases by many years. The table at Appendix A sets out agencies’ compliance in more detail. While not having a current child protection policy does not mean agencies are not fulfilling their responsibilities to identify and report on child abuse, it does suggest that this may not be a priority for those agencies whose policies are not up to date.

Recommendation 13

Regular public awareness campaigns should be undertaken so the public is attuned to the signs and red flags that can signal abuse and are confident in knowing how to report this so children can be helped. Aotearoa society needs to hear the message ‘don’t look away’.

The lead agency for recommendation 13 is Oranga Tamariki, although it is acknowledged that it needs to be supported by a multi-agency approach.

This recommendation was noted by Cabinet in 2022 as accepted. It is operational in nature or within the authority of Chief Executives to progress.

Status: Not achieved

A public awareness campaign has not yet been developed

Oranga Tamariki advised that public awareness campaigns will be an ongoing programme of work, and ideally become part of business-as-usual operations. It noted that budget constraints pose a risk for this recommendation and accordingly it is exploring other opportunities to advance child abuse prevention messaging. Oranga Tamariki is developing an awareness-building content stream on its external platforms where it can utilise existing content that may have been developed by sector and/or community partners. Despite accepting this recommendation in 2022 and being within the authority of the Chief Executive to progress, no public messaging or awareness has been progressed in response to this recommendation.

What we’ll look for in another 12 months on critical gap five

We will be looking to see how the system is responding to put the needs of tamariki front and centre, and what impact this is having for tamariki and their . This will include how children’s system agencies are working together and fulfilling their responsibilities. Ultimately, we will be looking to see how the system prioritises the needs of tamariki and makes them more visible.

5 https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-address-child-abuse-system-failings

6 https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/Reviews-and-Inquiries/System- review-Dame-Karen-Poutasi/CAB-22-MIN-0540-Final-report-by-Dame-Karen-Poutasi-on-the-death-of-Malachi-Subecz.pdf

7 CAB-23-MIN-0398-Report-to-Cabinet-on-the-progress-made-against-the-recommendations-of-the-Dame-Karen-Poutasi-system. pdf (orangatamariki.govt.nz)

8 The investigation and prosecution was undertaken by the NZ Customs Service.

9 Te Puna Aonui is an interdepartmental board which includes the Accident Compensation Corporation, Department of Corrections, Ministries of Education, Health, Justice, and Social Development, New Zealand Police, Oranga Tamariki and Te Puni Kōkiri. There are four associate agencies – the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the Ministries for Women, Pacific Peoples, and Ethnic Communities.

10 https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/our-health-system/digital-health/hira-connecting-health-information/

11 This does not include reports of concern from the NZ Police related to family violence, which are recorded separately by Oranga Tamariki.

12 This figure is based on the 2018 New Zealand census from data available on the Stats NZ website, (stats.govt.nz)

13 Throughout this report, unless specifically stated otherwise, we refer to the number of reports of concern progressing to assessment or investigation (Further Action Required; FAR) based on the final decision made by Oranga Tamariki sites. This final site decision is subsequent to the much higher number of initial FARs made at the National Contact Centre.

14 https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Research/Latest-research/Analysis-of-the-decrease-of- Reports-of-Concern/Analysis-of-the-decrease-in-Reports-of-Concern.pdf