Agency reviews

The six agencies that commissioned the Poutasi review each also completed their own reports into their interactions – direct and indirect – with Malachi, his mother, wider , and Ms Barriball. In this section we look at each of those agency reviews, the recommendations arising from them, what has been done in response, and what has changed as a result. This is set out in broadly the chronological order in which each agency was involved, although we note there were overlaps in when agencies were respectively engaged.

Reports of concern

How Oranga Tamariki receives, records and responds to reports of concern is important context for understanding its response to Malachi, and the subsequent changes it implemented.

When agencies or members of the public have concerns for the safety and/or wellbeing of , they can either call, or email/fax/mail the Oranga Tamariki National Contact Centre (NCC) or go into an Oranga Tamariki site to discuss their concerns. They can also contact NZ Police. These become reports of concern when the information is assessed to meet the definition under section 15 of the Oranga Tamariki Act.

If a report is not considered by Oranga Tamariki to meet the definition under section 15, it may instead be recorded as a contact record. Information may also be added as a case note for open cases, including where there is additional information relating to concerns that are already being assessed or investigated15.

Oranga Tamariki carries out an “initial assessment” on all reports of concern. This is to determine what response is required.

In response to our information request, Oranga Tamariki told us that since late 2021, it has gradually centralised responsibility for initial assessments. It told us that most initial assessments are now completed by the NCC (approximately 75 to 80 percent of all initial assessments, across 42 of the 60 Oranga Tamariki sites nationwide)16. However, cases where it is clear that tamariki require further assessment, such as critical or very urgent reports of concern (48- or 24-hour timeframes) and those cases that require an investigation under the CPP go directly to sites with little work done on the initial assessment.

An initial assessment can include contacting the person making the report of concern, as well as others, to develop an understanding of the needs and vulnerability of the tamariki, and to develop a chronology.

Decisions on initial assessments may be that no further action is required, to refer the child to a community agency, or that either a child and family assessment or an investigation under the CPP is needed. The phase of assessment that further

investigates a report of concern after initial assessment is called “core assessment”. The site may subsequently decide to overturn an initial assessment decision made by the NCC and instead refer the child to a community agency or determine that no further action is required.

Reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki about Malachi

On 21 June 2021, Malachi’s mother asked Michaela Barriball to have care of Malachi.

On 22 June 2021 Malachi’s cousin went into an Oranga Tamariki site to make a report of concern about Malachi. The site entered the information and transferred it to Te Āhuru Mōwai site for initial assessment. The next day, after Malachi’s cousin called the social worker back with further information, a case note was added to the report of concern to note the additional information provided. On 28 June, Malachi’s cousin contacted the duty social worker at Te Āhuru Mōwai site to provide further information, including that she had a photo that she thought showed bruising around Malachi’s eye. On the advice of the social worker, Malachi’s cousin emailed the photo to the NCC and asked for it to be attached to the report of concern.

On 29 June, the report of concern was allocated to a social worker at Te Āhuru Mōwai site to complete the initial assessment. The social worker allocated was the same social worker who had spoken to Malachi’s cousin the day before. In reviewing the information in the report of concern, the social worker determined that while Malachi had unmet needs, there were no care and protection concerns for him and determined no further action was required by Oranga Tamariki. The following day, this decision was signed-off by a supervisor.

The social worker contacted Malachi’s cousin to advise of the decision and recorded a case note on CYRAS.

At the time of making the initial assessment decision, it was not standard practice for Te Āhuru Mōwai site to make referrals to agencies for support as part of an initial assessment. Accordingly, there was no referral, and the report of concern was closed with no further action.

Following Malachi’s death, the Office of the Chief Social Worker in Oranga Tamariki undertook a practice review looking at how Oranga Tamariki responded to the reports of concern made for Malachi.

What the Chief Social Worker’s review found

The Chief Social Worker’s review identified four areas which contributed to Oranga Tamariki failing to provide Malachi and his with the right response. Those four areas are:

- the practice guidance, professional development, and inter-agency processes which require strengthening to support social workers to consistently recognise and respond to the complex needs of tamariki and whānau

- practice decision making that fell short of what was required to deliver a quality service to Malachi and his whānau, including the decision not to progress the initial assessment to an assessment that involved seeing Malachi

- the wider community and system which did not communicate or respond in a connected way using a locally-led, partnered approach to the initial report of concern

- the site environment, support and leadership which impacted on the ability of social workers to deliver best practice.

In response to the Chief Social Worker’s practice review, in November 2022 the Oranga Tamariki Leadership Team – Te Riu published a response that outlined what had already been done, and what more would be done over the next six months. The response included 30 recommendations to address immediate issues, 11 which had already been addressed, and 19 which were to be completed between December 2022 and May 2023. At the time of our review, Oranga Tamariki advised that all 30 recommendations in the initial response were complete, and that broader issues would continue to be taken forward through the Future Direction Plan and broader change programme.

We wanted to understand if the changes made in response to the Chief Social Worker’s practice review are achieving the intended impact. To this end we engaged with kaimahi from Oranga Tamariki in the NCC, sites across the Auckland, Bay of Plenty and Canterbury regions, and in national office. Much of what we heard, aligned with what the Ministerial Advisory Board heard and reported on in its 2021 report Kahu Aroha17.

Most of the Chief Social Worker’s review focused on practice at site. Despite Oranga Tamariki advising that initial planned actions to implement it have been completed, we heard that practice at the sites of the social workers we spoke with, has not yet substantively changed for them. This is because some of the planned actions are focused on addressing symptoms such as reminding staff about using practice guidance, one-off training opportunities and reviewing tools on performance development. While these are important ways to improve practice, if the root causes of practice issues are not addressed, only limited change can occur. Oranga Tamariki told us it is also trying to create broader change through the practice shift. We discuss this further below.

Practice guidance, professional development and interagency processes

The practice guidance, professional development, and inter-agency processes which require strengthening to support social workers to consistently recognise and respond to the complex needs of tamariki and whānau.

Status of response: Oranga Tamariki advise this is complete

The Chief Social Worker’s review identified some gaps in existing practice guidance, professional development, and processes for working with partner agencies about responding to reports of concern. The review found that it is likely these gaps contributed to limited engagement with others (including Malachi and his whānau) during the initial assessment, a failure to recognise underlying factors which may have impacted on Malachi’s care, and a lack of consultation with other professionals, particularly around the possibility of physical abuse.

Changes to practice guidance may be minimising child safety

Oranga Tamariki told us that in response to this finding it undertook reviews of policy and guidance and made several changes to strengthen practice. The intent of the changes was to ensure there is clear direction about recording and assessment of photographs and other ‘additional information’ received following an initial report of concern. This was to ensure that Oranga Tamariki responds to reports in a way that is consistent with legislation and best practice expectations.

Changes were made to the initial assessment phase guidance, including broadening who can be contacted at this point, to determine whether a core assessment is required. Current guidance on the Oranga Tamariki Practice Centre now says:

… in some circumstances it may be appropriate to speak directly with tamariki, whānau or family as part of our initial assessment. Understanding how whānau or family see the situation for te tamaiti, whether they have concerns or are stepping in to provide support, can help us reach a decision about the appropriate response.

It may also be appropriate to gather information related to the notifier’s concerns from other agencies (such as schools, early childhood educators, health professionals, NGO providers and ) who know te tamaiti and their whānau or family. We may also receive information from the notifier or another concerned person who proactively contacts us after the initial report of concern with information they believe is important. This may include visual information such as photographs.

The purpose of this change was to allow social workers to gather more information during the initial assessment. This change could improve decision making, provided risks associated with contacting parents and whānau at this stage are managed. However, there does not appear to be any further guidance around assessing the risk of doing this. We also heard from Oranga Tamariki kaimahi in sites that although in many cases parents are now contacted during an initial assessment, tamariki are not spoken to or seen. While the practice change may have increased engagement with parents, feedback from kaimahi we spoke with suggests it has not increased the visibility of the child in the decision-making process.

A consistent concern we heard from the social workers and supervisors we spoke with was that tamariki are not at the centre of decision making. We heard how the practice shift, while positive in some respects, seems to conflict with the child protection lens. We also heard that those working for Oranga Tamariki and their colleagues in community and government agencies are not clear about the role of Oranga Tamariki.

“There is also a lack of basic understanding of our statutory role. We have great social workers that have come from community, but they don’t get the statutory part of the job.“ - site leadership

Kaimahi recognised the importance of whānau, and including them in decision making, but they felt that Oranga Tamariki had “gone too far”, and there is no longer a sufficient focus on the safety of the child and keeping the holistic needs of the child at the centre of decisions. They felt that their role as statutory social workers was less clear, and this was reflected in training they receive. This was a concern raised in 2021, by the Ministerial Advisory Board’s report Kahu Aroha.18

“When we are talking about the new learning courses, it’s had a focus on see and engage, whakawhanaungatanga. It took away from the core statutory focus. People say whānau-led, whānau-led, you can be whānau- led but you still have to assess safety and risk, what is your statutory role, what is it we have to do? While all this learning has been good, it’s taken away the purpose of statutory work.” – site kaimahi

The Poutasi review was clear that for government sector agencies, tamariki are not always at the centre of the identification of and response to child abuse. This includes Oranga Tamariki (the agency at the heart of child abuse identification and response) which also failed to detect red flags and prioritise Malachi’s safety.

“Malachi did not have a voice: he was not seen or focused on. We should have a child protection system that, across multiple agencies and our society, looks at and listens directly to the needs of the child themselves rather than just the adults around them. Children must be given a voice across the system that is intended to support their needs and that seeks to describe itself as child centred. We need to turn this aspiration into a reality.” - Poutasi review

This issue is not new. The Poutasi review identified eight previous reviews that were particularly relevant, that highlighted similar circumstances and gaps in the system. Of particular relevance is a Chief Social Worker Review into the deaths of Olympia Jetson and Saliel Aplin which found a lack of focus on the child and decisions to work through adults and parents when determining whether a child was at risk.

“Whenever a notification of abuse is received, the first step is to secure the safety of the child, before beginning any investigation. This recognises that the very process of investigation, making enquiries and gathering information, may endanger a child. The process of inquiry, the asking of a question, conveys the issue at the heart of the inquiry. Care must be exercised when communicating the reason for the inquiry.” - Review 200319

What we heard in our engagements, particularly in the Bay of Plenty region, is that the invisibility of tamariki in the system has not changed:

“It’s a flash in a pan, everything comes out then we forget about it. Wheels keep on turning, then we lose focus on all the reports. Tamariki should be at the centre of everything. Currently, I don’t see tamariki at the centre, they’re not even on the table. I got some practice notes, they come out, but we should be living them, but we’ve drifted away from tamariki.” – site leadership

Overall, what we heard from kaimahi was that they felt best practice has shifted towards emphasising organisational values, and relationship building.

Oranga Tamariki national office told us that while it is aware that in some areas, interpretations of the practice shift suggest it is defaulting to entirely whānau-led decisions with a reduced emphasis on safety or risk, this is not an accurate reflection of the practice shift, or training.

National office leadership advised us “the scale of change required is significant, as was identified in the Ministerial Advisory Board’s 2021 report Hipokingia ki te Kahu Aroha Hipokingia ki te Katoa and the journey to fully introduce and embed this approach is not yet complete. Some sites and regions are at different stages in their learning and understanding and more work is needed to ensure all staff understand how to apply the practice approach within the context of their statutory role. However, most staff are seeing the value in the practice approach, including that it is enabling them to respond differently and more comprehensively to issues of child safety and risk in their practice whilst also working in ways that build strengthened relationships with whānau”.

National office assured us that assessment and practice places a view of risk within the broader context of the child’s wellbeing. It explained that some of the sites and regions we visited have not implemented training to support the new “oranga framing” to the same extent as others. We did hear from the sites we visited that they do work to the practice standards and the oranga framing, as much of it is “what social workers already do”, and it is just re-packaged.

Despite this explanation from Oranga Tamariki national office, it was apparent that the views of the kaimahi in the sites we visited were that practice had shifted to a whānau focused rather than whānau informed approach. Regardless of the intent behind the policy or guidance, if this is not understood by the frontline, it results in a failure of implementation.

We heard induction and training are not adequately supporting some social workers

Oranga Tamariki told us its Puāwai induction training and Leaders in Practice professional development programmes were launched in January 2023. In addition, work was undertaken to develop additional learning resources for all practice staff, ensuring that the critical learning needs identified in the Chief Social Worker’s practice review are embedded within the core curriculum. The intent of this work was to support social workers to consistently recognise and respond to the complex needs of tamariki and whānau.

Oranga Tamariki national office leadership told us that “the introduction of the new practice approach has been coupled with a focus on strengthening our learning and professional development offer through programmes such as Pūawai induction for new social workers, a leaders in practice programme, the postgraduate kaitiakitanga bicultural supervision programme, fortnightly site based learning referred to as He Akoranga and a range of additional learning opportunities supported through the Chief Social Worker’s development fund.”

National office advised us it has received extensive feedback from kaimahi who have completed learning cycles, who have provided compelling feedback about the benefit of the training to their work.

We were told that as Oranga Tamariki “reset a learning and development culture within the organisation, some kaimahi have indicated that it is difficult to find the time and space to participate fully in all learning and some may feel there are still gaps in the learning offer. Overwhelmingly, most of those who have participated in these learning opportunities across the country are seeing them as valuable, have acknowledged an increased investment in their development and can describe clearly how their approach to practice is changing as a result of new learning”.

However, across sites in the Auckland and Bay of Plenty regions, most of the social workers and site leadership we spoke with told us that the induction and training does not adequately prepare or support social workers for the work they need to do. We heard that previous induction programmes better prepared kaimahi for the realities of the job.

One kaimahi said they liked how the induction training let them meet kaimahi from other sites and see other sites’ different practices.

Another kaimahi told us their high workload makes it hard for them to be invested in training, especially when they don’t feel the training is relevant to their . One leader told us that kaimahi spend too much time on training and personal improvement when they should be focusing on their work in the community. They felt there is currently too much focus on the kaimahi themselves, rather than on those they work with.

We heard positive feedback about fortnightly practice forums led by practice leaders and based on site need or reviews. We were told that most of the sessions are topics on tamariki in care, with very little about intake and assessment. One kaimahi suspected this is because there are not many reviews about the intake and assessment process.

NCC kaimahi have their own induction programme and NCC staff often rely on others throughout the organisation to share learning. In some instances, they have created their own tools to support practice.

“Since I’ve come on board, we been looking at our NCC induction because our social workers don’t go to our national [Oranga Tamariki] induction program.” – NCC leadership

“With national office, we almost have to make our own process systems and induction. We look at how they are run. There are gaps, building those relationships but again have you considered us, we are specialist with after hours, but you don’t even have us sitting at the table.” – NCC leadership

We asked kaimahi how they had been made aware of the practice standards, how they are being implemented and how they know they are achieving them. The kaimahi we spoke with about the practice standards were aware of them. Some felt that they naturally implemented the practice standards into their work.

“The practice standards are common sense and basic social work.” – site leadership

“We are starting to incorporate those [practice standards] concepts. The differences between the office is not much anyway, because the work is still being done. If we applied the practice framework to a lot of the cases we worked, a lot of the work is being done [as per the practice standards].” – site leadership

We were told that sites receive regular training on the practice standards, but this was not universally considered helpful. Some kaimahi told us they would rather have training on specific practices relevant to their work and incorporate the principles into those trainings.

We heard that communication from Oranga Tamariki regional and national leadership is not always clear and can get lost. Some site leadership kaimahi told us that there are “so many comms” that it is hard to keep up and that communication on practice changes were not clear.

“It [the practice changes] just appears [on the Practice Centre]. I don’t know where they come from.” – site leadership

Some leaders knew to share these changes with their team, while others either do not know to share it, or find it gets lost due to their workload.

What we see again is the difference between what we heard when we spoke with kaimahi in sites compared to what Oranga Tamariki national office tells us it understands. In summary, we heard Oranga Tamariki has developed and is part way through delivering training on the practice shift. There are mixed views from the sites on the value and impact of the delivery of the various training requirements. Those we spoke with stated they learn more from practical training that has clear messages on how they are supposed to work in a statutory context.

Practice decision making

Practice decision making that fell short of what was required to deliver a quality service to Malachi and his whānau, including the decision not to progress the initial assessments to a core assessment.

Status of response: Oranga Tamariki advise this is complete

The Chief Social Worker’s review found that Oranga Tamariki did not meet its obligations to Malachi or his whānau. Members of Malachi’s whānau made repeated, sincere and considered efforts to raise their concerns about the care, safety and wellbeing of Malachi, and the response of Oranga Tamariki was inadequate. It noted that correct practice was not followed to reach the decision to take no further action in response to the reports of concern made by Malachi’s cousin. A decision should have been made to undertake a core assessment and Malachi should have been seen as part of this.

Oranga Tamariki told us that in response to this finding, on 30 November 2022 the Chief Executive sent a letter of practice expectations to senior leaders with responsibilities for the delivery of services to tamariki and whānau. The letter set out that:

- only social workers with more than 12 months experience as a registered and practicing social worker will complete initial assessments, and that new social workers will be supported to complete their practice induction and focus on their learning

- the practice standards are minimum standards and his expectation is for managers and leaders to support social workers to understand and apply the practice standards in their work

- channels are available to staff to share concerns, and his expectation on managers to work with their teams in a way that creates a safe space for open and honest dialogue and where concerns can be raised, including anonymously if needed.

In addition, we were advised that on 5 December 2022, the Chief Social Worker issued a practice note about case recording. This noted that issues had been identified with inconsistent recording of all relevant contacts and information obtained from people involved with tamariki or whānau. On 20 February 2023, a message was sent to all Practice Leaders which included a slide pack presentation and discussion notes on the Practice Standard to ‘Keep Accurate Records’, for delivery to all frontline kaimahi.

Most initial assessments are made by the National Contact Centre

We wanted to understand how the changes made have influenced decision making both at the NCC and sites, particularly around reports of concern.

In response to our information request, Oranga Tamariki told us that:

- the NCC has embedded systems and allocated staffing to promote consistency in decision making across the country. This ensures that those completing initial assessments are sufficiently experienced. We were advised that the sites who continue to complete their own initial assessments are smaller sites, or sites who have a partnered assessment approach with key community and/ or iwi/Māori partners.

- the NCC has moved to a regional team structure. This allows them to become more familiar with tamariki and whānau in the particular region they service, as well as the community support agencies that are available.

When we visited the NCC, almost all kaimahi told us about the benefit in the shift from a centralised approach to regionally focused teams.

“It’s broken heaps of barriers with sites in [region], having face to face conversations really helped. [We are] getting to know our community better and community agencies. [It is a] totally different way of working that seems to be working.” - NCC kaimahi

“[It is a] far more collaborative approach, we keep close eyes on renotification intakes, we can have a joint consult for the best way forward for this tamariki or , we can have this conversation in the after- hours space too. It is a far more collaborative approach in getting the best outcome for our whānau. We often have social workers who work for NCC [National Contact Centre] who are based in Christchurch and the Hawkes Bay for example, and they develop that local knowledge, and it assists them to have that relationship with local whānau.” - NCC leadership

However, we were also told that within the regional teams there are different approaches to practice and intake social workers can be responsive to the needs of the local site.

“It depends on where you live and the service you get, but if we [NCC] were doing [all] initial assessments, we will have more consistency.” [NCC leadership]

When we asked Oranga Tamariki sites how the process with the NCC completing initial assessments was working, we heard that communication and consultation between the NCC and sites makes a difference. In one region a supervisor spoke of an increase in consultation around timeframes:

“That has been a change, I have noticed it’s different from previous years. The calls from the NCC to site from social workers has increased. There is a lot more consultation. They are asking us now what time frame should this [report of concern] be – it’s useful at times.” – site leadership

But we also heard about how delays and a lack of communication from the NCC impacts on site workloads:

“Sometimes they [NCC] upload [the intake] so late so we are already behind the 8-ball. We still have a full caseload, we drop that to meet the 10 day timeframe. They sort of, I feel that their expectations are a bit unrealistic. They make those decisions in isolation.” - site kaimahi

“Sometimes they’ve [NCC] had it for 10 days before they give it [to site] and there’s no communication around that.” – site leadership

We heard across regions that records from the NCC were sometimes inaccurate or incomplete. Although this could be corrected with a few phone calls, when this was done at site, it took time away from other casework.

The National Contact Centre is taking steps to improve quality assurance

We also looked at the checks in place to support quality decision making over reports of concern and initial assessments, at both NCC and in sites.

Overall, we heard that NCC staff had site experience, and were able to describe an environment where they had regular access to supervisors to support decision making. NCC leadership told us there is a greater level of oversight of the decisions made by new social workers and that these decisions are not made in isolation.

“For the new kaimahi, it is always a 100 percent sign off… Compared to site, our supervisors are sitting on the floor so there’s always that capacity for checking every piece of work.” - NCC leadership

Supervisors sign off on all decisions, and case sampling by the Practice Leader also supports good decision-making. It is important that the new Quality Practice Tool (QPT) is implemented to provide additional assurance and oversight to both the NCC leadership and national office.

National office advised that while the NCC does not currently complete quality assurance reports for national office, these are to be implemented in late 2024.

To support this a QPT is being developed, led by the NCC leadership team. The QPT contains a set of questions used by practice leaders to review randomly selected cases and determine if the quality of practice aligns with expectations in the practice policy, guidance and standards.

We were told that once implemented, the QPT will enable data to be generated on the NCC’s initial assessment practice. This will be able to support national level reporting if desired, as well as NCC-led continuous practice improvement activities.

The NCC leadership team told us that the impacts of practice changes were not always considered within the unique context of the NCC.

“… It was like NCC was here on this island and OT [Oranga Tamariki] national office was here on another island. There was a practice note that come out in 2022, saying basically by the way the Practice Centre has been updated, and by the way you can talk to whānau now, but it was treated as a minor change but actually that was a major change for us ... It was a big change that was minimised.” – NCC leadership

Sites use different quality assurance processes to check their decisions

In accordance with the Chief Social Worker’s practice review, we heard that sites were ensuring that decisions on initial assessments were not being made by social workers with less than 12 months experience. Where we heard about exceptions, we were assured that they never worked alone, and that there was adequate supervision and oversight of their work.

While almost all sites we spoke to over the three regions now use some form of collective review of initial assessments,20 the process used varied across the sites we spoke with. Two out of the three regions used the same decision response tool as the NCC to inform their decision, as required in policy. The other relied on the professional judgment of staff members. Sign-off of the final decision also varied. In some sites a single supervisor was responsible for the decision, while others used collective decision making.

Staff from Oranga Tamariki national office told us the expectation was that all sites should use the decision response tool to inform their intake and assessment decisions.

When we asked about whether quality assurance changes made as a result of the Chief Social Worker’s practice review are making a difference, all sites mentioned QPT. The results of QPT are used by sites to understand where they need to work on practice, and what they can do better.

While QPT has been focused on core assessment, Oranga Tamariki is currently using it to assess the quality of initial assessment decisions where the initial assessment decision is no further action. This is a positive step, as understanding whether the correct decision is being made at this stage is critical to keeping children safe.

In our interviews with kaimahi, we heard that the latest QPT checks, undertaken shortly before we spoke with sites, was focused on intake and assessment practice. We were told by frontline kaimahi that this was the first time QPT had focused on intake and assessment. At the time of drafting this report, the results from the QPT had not been fully analysed to be shared with us.

However, Oranga Tamariki national office advised that its approach to quality assurance is to ensure it is routinely reviewing and considering all aspects of practice, from initial assessment to care, over the course of the year. It further advised that case file analysis provides a second line of assurance. This is undertaken by Oranga Tamariki as part of its self-monitoring system.

The wider community and system

The wider community and system which did not communicate or respond in a connected way using a locally-led, partnered approach to the initial report of concern.

Status of response: Oranga Tamariki advise this is complete

The Chief Social Worker’s review found that the operating model for responding to reports of concern can result in isolated decision-making and is vulnerable to being used as a means of managing workload. It noted there was a lack of partnered decision making, resourcing, wider community and cross-government collaboration and information sharing when responding to reports of concern. It also noted that had agencies been more coordinated, it would likely have strengthened the response that Malachi and his whānau received.

Both the Poutasi review and the Chief Social Worker’s practice review noted the need to involve community agencies in decision making processes. The success of strategies to do this is varied. In some sites we heard that there were strong connections, and decision making envisaged in the Poutasi review is occurring. However, other sites felt they were unable to progress this area due to delays in approval from national office.

“…we’re not sure where it goes, it just gets lost. It’s the layers, the bureaucracy. We don’t get any autonomy.” – site leadership

Some also felt that the model of having the NCC complete initial assessments was a barrier to community involvement at the early stage.

”We get asked to be strategic, then get out there, then be told we can’t. We pull out the [Poutasi] report. We still can’t do it.” – site leadership

Kaimahi told us that communication is not always clear and that the messages they are getting are sometimes inconsistent.

“It’s great what is being said at the top, but by the time it gets to us we get the bare minimum at the bottom … People talk about hitting a glass ceiling, but we are hitting a brick ceiling, we can’t see what is on the other side. I get inspired by what Chappie [Chief Executive] and the leaders said at the top, but then we get the remixed version at the bottom. We need to be hearing the same message.” – site kaimahi

Given this feedback, we were interested in the views of other agencies, particularly around making reports of concern. We looked at what we had heard from agencies through our regular monitoring programme. Of note was that most agencies have told us they do not hear back about the outcome when they have made a report of concern, and this can affect their confidence that the right decision is being made.

“As a frontline [Police] officer we never hear what’s happening with a report of concern, we don’t know if it is being dealt with or not.” - police officer

Professionals in other agencies and we spoke with told us that they do not feel that their reports of concern are taken seriously enough or acted upon by Oranga Tamariki, that they do not hear back about the outcome of the assessment of the report, and that they feel discouraged from making reports of concern as a result of this.

“As I have become a more experienced social worker, I found that I didn’t want to put in a ROC [report of concern] because OT [Oranga Tamariki] don’t take them seriously and it goes nowhere but it wrecks my relationship with the family I work with.“ – Barnardos kaimahi

“What are the scenarios where OT would pick it up? What are the likely RoC [report of concern] that will hit OT [Oranga Tamariki] buttons, is there a word we can use? Well, if we don’t hear back, what’s the point. We’re not going to stop putting them in, it’s a duty of care of course, but it’s frustrating.” - school principal

Recent research21 has also identified that the process of deciding to report concerns to Oranga Tamariki is influenced by the threshold within Oranga Tamariki for accepting reports. That research found that “as the Oranga Tamariki threshold rises and its criteria change, it slowly, yet unevenly and with instances of resistance, affects the NGO heuristic and threshold”.

We also heard that in some regions, professionals in other agencies are making reports of concern to the NZ Police, rather than Oranga Tamariki, as they feel the NZ Police are more responsive to their concerns. While this is consistent with section 15 of the Oranga Tamariki Act, which states that a report of concern may be made to either the Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki or a constable of the NZ Police, reports of concern are most relevant to NZ Police if there is potential criminal activity (such as abuse). If the concern prompting the report is solely around care and protection, it must be assessed by Oranga Tamariki in the first instance. We also understand that as per the relationship agreement between the NZ Police and Oranga Tamariki, concerns raised with the NZ Police that are solely of a care and protection rather than a criminal nature are meant to be referred directly to Oranga Tamariki.

Report of concern data does not necessarily reflect need

Having heard from professionals in other agencies that multiple reports of concern are required for Oranga Tamariki to act, we wanted to understand whether this was reflected in the data on reports of concern. In particular, whether multiple reports of concern needed to be made before reports of concern were progressed to investigation, and whether this differed by the notifying agency. However, data on reports of concern did not necessarily show this was the case.

Data provided to us by Oranga Tamariki shows that in 2022/23, for all the tamariki for whom a report of concern was made, 75% of them had only one report recorded for them, and 92.5% of tamariki had up to two reports recorded for them. Oranga Tamariki could not yet tell us how many of these tamariki had contact records as well as reports of concern. This would give us a better understanding of the number of times Oranga Tamariki had been contacted about tamariki it had recorded reports of concern for. Oranga Tamariki advised that it is looking at understanding this further as part of case file analysis is has underway.

Oranga Tamariki data also shows that for all their investigation or assessment decisions in 2023, in 81% of these cases only one report of concern was made prior to the decision, with up to two reports being made in 96% of these decisions. There has been little change in these figures since 2016.

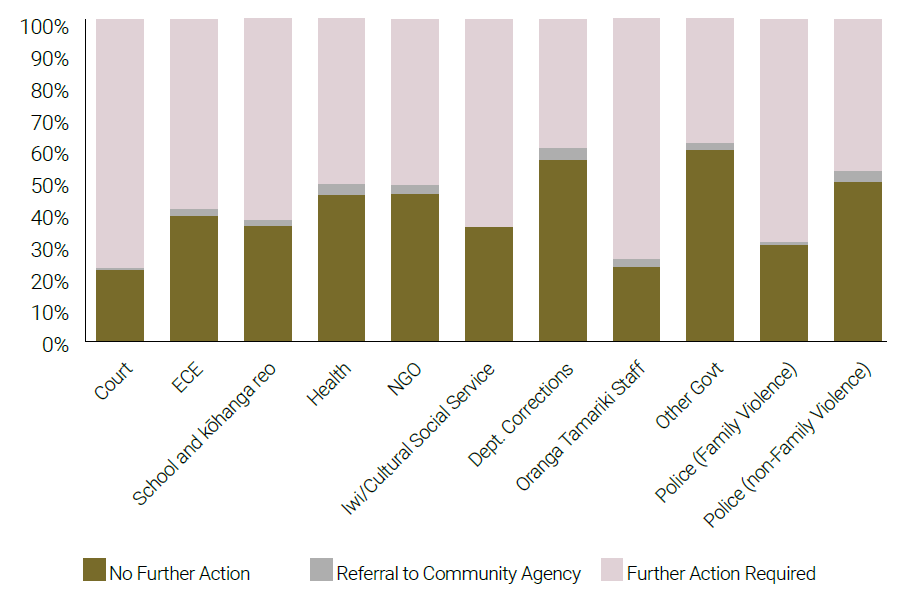

The graph below shows the report of concern decisions made by Oranga Tamariki in 2023, broken down by the notifying agency. The percentage of reports resulting in further action required varies by notifier type22. Decisions to take further action were made in a lower proportion - around 40-50% - of reports of concern received from NGOs, Health, Department of Corrections, Other Government, and NZ Police non-family violence.

Graph 3: Oranga Tamariki response to Reports of Concern by notifier type in 2022/23

A high proportion of reports of concern from professionals do not result in further action by Oranga Tamariki

Graph 3: Oranga Tamariki response to Reports of Concern by notifier type in 2022/23

Based on this, we conclude that looking at data on reports of concern in isolation does not necessarily provide an accurate view. It is evident from the data and in what we have heard, that those who do make reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki may be operating on different thresholds for when to report. Additionally, the data does not account for contact by agencies that was recorded as a contact record or additional information instead of a report of concern. There is also a possible issue of trust in Oranga Tamariki and lack of confidence that it will respond to address need in response to reports of concern.

We also heard in our wider community monitoring that NGOs will try to work with families for as long as they can before making a report of concern. They told us that when they do report concerns it is because they are serious enough for Oranga Tamariki to become involved, however, nearly half of all reports of concern are assessed by Oranga Tamariki as requiring no further action.

Site environment, support and leadership

The site environment, support and leadership which impacted on the ability of social workers to deliver best practice.

Status of response: Oranga Tamariki advise this is complete

The Chief Social Worker’s review found that at the time of their involvement with Malachi and his whānau, social work staff at Te Āhuru Mōwai site were experiencing workload and resourcing issues that were having a direct impact on their practice. In addition, a broader range of known process, culture, leadership, and stakeholder relationship issues were also present, had not been addressed and likely contributed to decisions made about Malachi.

Oranga Tamariki national office told us that it considers that it has implemented a comprehensive plan for the Bay of Plenty region that addresses the broader workload, leadership, development, stakeholder relationship, practice and cultural issues identified by the review.

Having visited the site, these issues have not been completely resolved. Further, kaimahi across all sites we visited talked about not feeling supported, not being listened to or asked what they needed in order to do their job. The experience of Te Āhuru Mōwai is reflective of this.

Staff we spoke to wanted more support from regional and national leadership

We were told at Te Āhuru Mōwai that there was an initial response after Malachi’s death, with additional staff coming in from other sites from March 2022. This provided short term relief. This support focused on managing workloads and issues that arose but did not address staff wellbeing to the extent required. Staff told us they were not asked what help they needed, that this was a site in crisis prior to Malachi’s death, and that their physical environment was not supporting good practice and physical wellbeing. This impacted on staff retention and recruitment, and the site continues to feel unsupported by its community, government partners and its own organisation.

We heard in the Bay of Plenty region that when social workers are working in the community, it is not uncommon for Malachi to be mentioned as an acknowledgement that they are not trusted to make the right decision.

Despite this kaimahi spoke positively about their current site manager, and the difference he is making, in spite of the challenges that remain.

What appears to have occurred is that focus and resources were deployed at the time of Malachi’s death. Steps were taken to address immediate needs, and it was assumed that the problems had been resolved. However, from speaking with staff and leadership at the site it appears that short term solutions were applied, and symptoms addressed but not underlying causes. As a result, staff lack confidence in the organisation and their own practice.

We were told that in the Bay of Plenty there is now more consultation with (and between) supervisors, because staff now lack confidence in their decision-making and skills. This was thought to be a result of the lack of support, as well as the community response.

“I spend a huge portion of my day going over cases with social workers.” – site leadership

It was also acknowledged that the confidence of supervisors at Te Āhuru Mōwai has been negatively impacted since the review, but that the leadership team is more transparent and willing to discuss issues, which is a positive shift. We heard that Oranga Tamariki made sweeping changes to the site’s leadership after the practice review, and the new leadership is invested in their mahi and helps to break down silos.

We were also told how frontline staff at Te Āhuru Mōwai support each other. There was a view that they are lucky to have the kaimahi they do, but also a realisation that this could change at any time. There was concern about public sector budget cuts and the impact of this on tamariki, rangatahi and their whānau. We heard the region is not allowed to access fee for service arrangements23 or resource workers. This meant that social workers have to do additional work such as staying overnight with tamariki and rangatahi in motels and taking tamariki and rangatahi to see their parents for access arrangements in the weekend. Kaimahi across all regions described lacking confidence in, and support from, regional and national leadership.

Oranga Tamariki national office disagreed with this perspective. It told us it could provide numerous examples of supporting and enabling the region with care arrangements from a national perspective, including the approval to employ resource workers, fee for service arrangements, and the creation of care contracts in the region.

Barriers to recruitment are affecting practice

The Chief Social Worker’s practice review noted that when workload pressures are high, a greater tolerance for risk may occur and reasons may be found to close an open case rather than exploring the best response to what may be occurring within or needed by the whānau. The review was also clear that the work of Oranga Tamariki must always be based on responding to the safety and wellbeing needs of tamariki and whānau. It stated that “effective leadership strategies are needed to ensure this focus is not compromised by high workload and demand”. It further noted that high demand, workload and case complexity is a known feature that is impacting on the social work workforce within Oranga Tamariki and more broadly across the sector. Oranga Tamariki noted it has work underway as part of the Future Direction Plan to address this.

However, we heard in sites that very little has changed, despite actions taken as a result of the practice review.

Leadership in the Bay of Plenty region understood that they were subject to a staffing freeze and this has affected staff capacity to manage workload. We heard that while some roles can be hired, information sent from national office about the full-time hours for each region meant they could not hire as many people as they need. In the Bay of Plenty region we were told:

“It’s all driven to save money. I’m tracking towards seven vacancies; I was told last night I can take on two social workers.” – site leadership

The issue with recruitment was not limited to the Bay of Plenty. We also heard in Auckland and Canterbury that they have been understaffed for a long time. Their high caseloads mean their outputs are not as high quality and they may miss deadlines.

“Until we have reasonable caseloads, like 10 – 14 tamariki [per social worker], we are never going to do good enough work.” – site leadership

Oranga Tamariki national office told us there was no staffing freeze on social work roles. It told us that recruitment is a sector-wide challenge and it has approximately 160 social worker vacancies across the country at present.

In one region we were told that high caseloads cause kaimahi to quit, leading to a low staff retention rate and an increase of inexperienced staff.

We also heard that staff capacity was an issue in some sites because some social workers were leaving to take regionally based roles with the NCC. We were told that these roles are considered more attractive as kaimahi can be based anywhere in the country, work from home and also not have to undertake after hours duties. However, national office advised that, aside from a few exceptions, NCC kaimahi are required to work from a site and that latest recruitment rounds include an expectation of after hours work.

Oranga Tamariki is struggling with the volume of reports of concern it receives. Decisions on which cases to intervene in are often made based on capacity. A recent report from Oranga Tamariki suggests that the volume of reports of concern may be decreasing, although it cannot say that this correlates to a reduction in need24.

We heard about the lack of clarity of the statutory role of Oranga Tamariki, and not enough education on how to identify signs of abuse or neglect for professionals, particularly when studying or training for their roles as NZ Police, doctors, or pre-school teachers. In parallel, work is needed to rebuild trust that Oranga Tamariki will respond to those reports of concern in the manner required.

We asked national office how it identifies when a site is potentially in crisis. In response they told us about heat maps across the regions, and that these indicated more support was needed across most of the country. We were told that the heat maps involve structured data from a range of sources being analysed across all sites. This supports Oranga Tamariki national office to understand current capacity across sites to carry out initial and core assessment work. They are designed to identify sites that may need additional assistance or support, or where there may be pressure points impacting on practice.

When we asked what Oranga Tamariki does to respond to this need, we were told that addressing the challenges faced by sites is difficult. As an example, they told us social workers’ contracts are often site based and do not always allow for social workers to be moved between sites to address need. National office told us there are practical interventions for sites such as providing site coaching and support. It also told us that during periods such as Christmas, it also deploys experienced social workers from national office out to sites.

Resourcing is impacting on decisions to intervene and take further action

A consistent theme we heard from all sites was that decisions about the need for an assessment are often made based on resourcing and workload, and this increases the risk that cases requiring follow-up are missed.

“If we were to allocate every report of concern from the contact centre, oh lord, our social workers would burn out.” – site leadership

“My understanding is that we [sites] are to accept everything [as it is assessed by the NCC] but sites don’t because of workload. NCC has always been way more cautious than sites. There is no consequences [for NCC staff], no flow on effects for pressures on staff. Sites go we can’t possibly look into these concerns because we have other work.” – site leadership

Some kaimahi told us that despite the regional approach, there is still a disconnect between the NCC and local sites and that NCC decisions are not always accepted by sites.

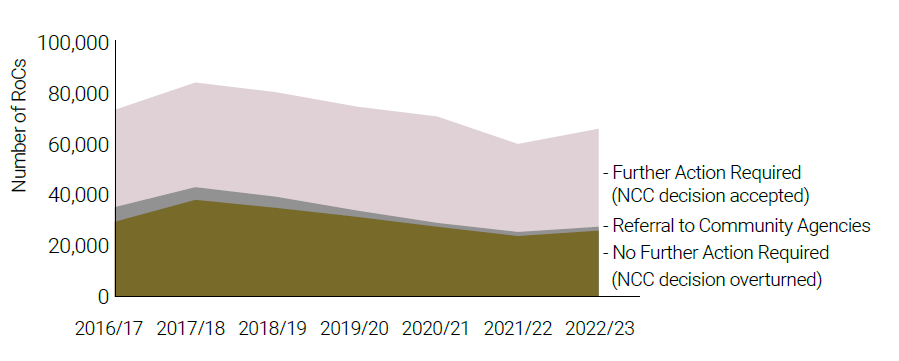

In trying to understand the size of this issue we looked at the number of initial assessments that are amended at site from further action to no further action. Oranga Tamariki data shows that around half of all initial assessments forwarded to sites from the NCC for further action are overturned (see graph below) and that the number of accepted decisions for further action is fairly stable, regardless of the overall number of reports.

Graph 4: Site response to Further Action required decisions at the National Contact Centre over time

Further action decisions by the National Contact Centre are re-worked by sites and around half are overturned

Graph 4: Site response to Further Action required decisions at the National Contact Centre over time

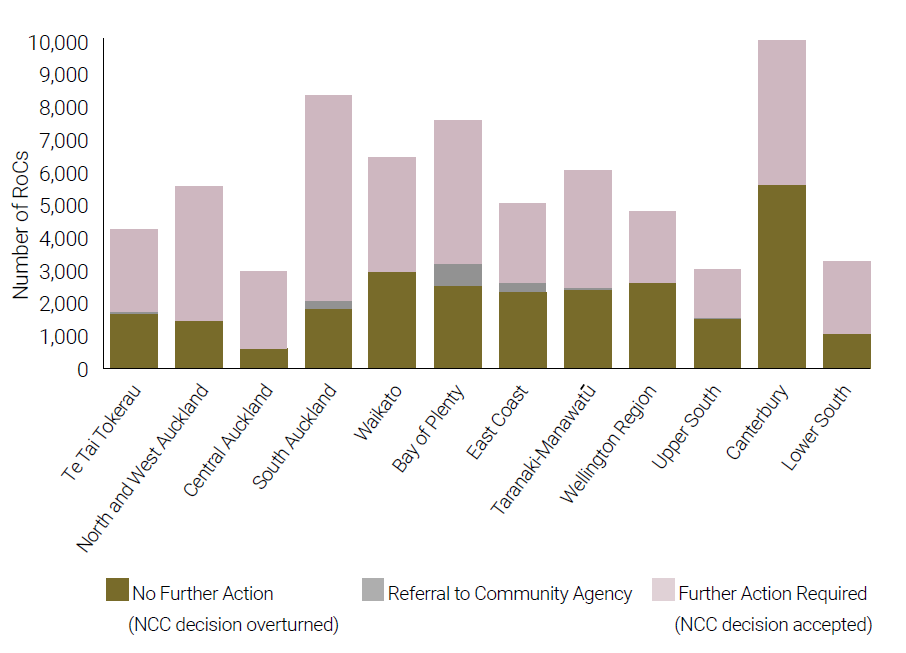

We then looked at the difference across regions, which shows variation in acceptance rates of NCC decisions. In particular, the Auckland sites had higher acceptance rates of NCC decisions, with the reverse in Canterbury. We note that as well as having a lower acceptance rate of NCC decisions, the Canterbury region receives a larger volume of reports of concern than other regions.

This aligns with what we heard about the closeness of the relationship with the NCC and sites. The thresholds for intervention also seem to vary by site. For example, we heard that a site with few reports of concern was accepting all NCC recommendations and progressing every case to core assessment. In other sites, where the numbers of reports of concern were much higher, sites were using different approaches to review NCC recommendations. Sites should have enough resource to investigate and address cases of concern, but we heard that generally they do not. The graph to the right shows the variation in acceptance of NCC decisions across regions.

Graph 5: Site response by region to further action required decisions at the National Contact Centre in 2022/23

Acceptance of National Contact Centre further action decisions varies significantly across regions

Graph 5: Site response by region to further action required decisions at the National Contact Centre in 2022/23

Where the site decides not to progress a report of concern to a core assessment, it is possible that it is referred to a community agency and this provides an opportunity for tamariki to be seen. Some of these referrals are reflected in the data, but Oranga Tamariki accepts that referrals to community agencies are underreported. The kaimahi we engaged with stated it is not standard practice for Oranga Tamariki to record referrals to community agencies. As a result, most referrals to community agencies appear as no further action decisions and there is no tracking of how many reports of concern are being addressed by the community and how many result in no action at all.

We heard from frontline Oranga Tamariki kaimahi that in some communities the capacity to respond to reports of concern at a community level is stretched. We heard that despite this, there is still a practice within Oranga Tamariki to refer cases to community agencies, regardless of the capacity of those agencies to respond to the need.

Tamariki are no more likely to be seen now than when Malachi died

Based on what we have heard from kaimahi and what we see from the data, we cannot be confident that tamariki in similar situations to Malachi are any more likely to be seen or kept safe than when Malachi died.

Overall, Oranga Tamariki is not making the best use of the resources it has to respond to the number of reports of concern for tamariki, and sites are spending time re-assessing further action required decisions made by the NCC. We also heard from Oranga Tamariki kaimahi that their interpretation of the practice shift placed greater emphasis on relationship building with whānau, even when there are situations where there may be safety concerns for tamariki. This is impacting on site decision making, and other agencies and NGOs are saying the threshold for statutory intervention to keep tamariki safe remains too high and unclear.

As a result, trust and confidence of agencies and NGOs is eroding, with a decline in the number of professionals making reports of concern.

While there are many community and iwi/Māori agencies in New Zealand, they often struggle with a lack of funding and uncertainty about contracts being continued, and sometimes do not have enough capacity to meet the demands of families in need. The gap between a community response and a statutory one also appears to be widening. We heard that many agencies will work with families to try to keep them out of the statutory system, but when they do need to make a report of concern there is no action from Oranga Tamariki, or it is referred directly back to the community.

We heard about lack of clarity about the statutory role of Oranga Tamariki, and that there is not enough education on how to identify signs of abuse or neglect for professionals, particularly when studying or training for their roles as NZ Police officers, doctors, or pre- school teachers. If this was addressed it would help ensure that those tamariki who need to be, are reported to Oranga Tamariki. In parallel, work is needed to rebuild trust that Oranga Tamariki will respond to those reports of concern in the manner required.

As already noted in our review, around half of all initial assessments referred from the NCC to sites for further action are overturned to become no further action by the site. Community and iwi/Māori agencies need to be supported to respond to tamariki and whānau needs, leaving Oranga Tamariki to focus on those tamariki and whānau who require statutory intervention. This requires a well-funded and -resourced NGO sector. If this is not achieved, tamariki and whānau needs will remain unaddressed, and over time are likely to worsen. Ultimately this will lead to further notifications to Oranga Tamariki, but with more entrenched needs that are harder and potentially more costly to address.

Aotearoa New Zealand has a way to go. Oranga Tamariki is trying to achieve this vision through its Future Direction and Enabling Communities approach, but it is not there yet. It also requires support from across government, and particularly the children’s agencies. In our monitoring we heard how, when other government agencies make decisions in isolation that impact on the wellbeing of tamariki and whānau, it has a flow on impact on reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki. Examples we heard were Kainga Ora evicting tenants, or NZ Police pulling back from family harm. Rather than working together as children’s agencies to collectively make decisions that benefit tamariki, agencies remain in silos.

In order for the system to be able to respond to meet need, these gaps must first be addressed, before considering additional demands and changes such as mandatory reporting.

The Department of Corrections undertook a review of its management of Malachi’s mother. We have considered the condensed, publicly available summary of the review, as this review covers the aspects that relate to Malachi.

The overall review made twelve recommendations, eight of which were included in the summary review as being of relevance to ensuring the safety of dependent children. Corrections advised us that as of 29 February 2024, five of these eight recommendations were complete. Below is a summary of the recommendations and what remains outstanding.

Recommendation one

Corrections must undertake a review of the Relationship Agreement with Oranga Tamariki, and thereafter ensure a review is undertaken every two years.

Status: Not achieved

Corrections advise that work has commenced to update the current agreement and update/consolidate the schedules (such as the information sharing schedule). Once this is complete, it will update the guidance for reports of concern and information requests. Corrections further advised that it has an ongoing relationship with Oranga Tamariki and the agencies continue to work together on emerging issues.

We asked Corrections why they have been unable to review their relationship agreement with Oranga Tamariki. Corrections told us that while it has resource available to progress this work, Oranga Tamariki has not yet resourced this work. Given the recommendation proposes the relationship agreement be reviewed every two years, there are implications for future reviews if those reviews also take as long to progress.

Recommendation two

Corrections must review and refresh its induction processes to ensure that information about a prisoner’s dependent children in the community is identified and recorded. Corrections must consider the Bangkok Rules25 and the Inspection Standards as it refreshes its induction processes.

Status: Not achieved

While considerable work has been undertaken, this action is not yet fully achieved.

Corrections advised it has reviewed and updated the Immediate Needs Assessment (which forms part of the reception into custody process) to include more open-ended questions with the purpose of strengthening the quality of information being provided to ensure Corrections can offer a more supportive response to individuals. The question regarding childcare arrangements has been updated with the intention to provide for further discussion with those coming into prison regarding any dependents they may have. Corrections is also trialing asking an additional question on whether women were breastfeeding/lactating prior to entering custody, in order to ensure these women have access to their immediate health care needs. Corrections advised it is also working through the process to make changes to incorporate questions about women who have aged under 2-years, to ensure they are getting timely information and access to Mothers and Babies Units and/or Feeding and Bonding facilities.

Corrections further advised that in August 2023, it tested an updated Immediate Needs Assessment at Auckland Prison, Mt Eden Corrections Facility, Auckland Region Women’s Corrections Facility and Spring Hill Corrections Facility. These sites were chosen for He Ara – A Pathway for Whānau, which seeks to support Māori who have been sentenced to imprisonment or remanded into custody, to put their affairs in order when coming into the Corrections system. The goal is to improve the wellbeing of whānau. When a person is received at these sites, they are now offered a referral option for their whānau to Te Pā. This is a kaupapa Māori organisation responding to community needs and providing reintegration and social services for whānau who are either in the justice system or exiting the system.

Corrections told us examples of how Te Pā has supported whānau by providing food parcels, clothing, nappies, hygiene and care packs, dental work, registering tamariki with doctors and supporting whānau to attend these appointments. Te Pā has also supported whānau with getting Well Child Tamariki Ora checks completed for tamariki, and enrolling whānau in training courses and obtaining driver licences.

In addition, Te Pā Navigators have supported whānau to maintain contact with the individual in prison. They have provided financial assistance through their child travel fund for whānau to visit, and obtain birth certificates to support prison visitor applications.

Recommendation three

Corrections must review its processes for approving telephone numbers, particularly for prisoners with dependent children in the community.

Recommendation four

Corrections must remind staff of the requirement to follow practice guidance for video calls at all times.

Recommendation six

Corrections must remind staff of the responsibility to ensure that prisoner information is appropriately recorded and stored.

Recommendation seven

Corrections must remind staff of best practice when correcting errors in official documents.

Recommendation eight

Corrections must ensure that review risk assessments are completed in accordance with the Prison Operations Manual.

Status: Corrections advise this is complete

Corrections advised that as a result of the internal review, a lessons learned process was undertaken in February 2023. This was chaired by the Chief Custodial Officer and attended by all General Managers. All General Managers were advised to share the recommendations at site level and encourage discussion to remind staff of practice guidance. The Chief Custodial Officer followed up to ensure that all matters had been addressed on site.

Recommendation five

Corrections must review and refresh its processes in cases where there is a report of concern about a child. As part of this review, Corrections must engage with key agencies, including Oranga Tamariki and NZ Police.

Status: Not achieved

Corrections advised that work to review and refresh its processes in cases where there is a report of concern about a child is ongoing. In 2021 Corrections added the report of concern process to its Online Refer system, which is technology developed to replace paper-based referrals to external providers. This system allows Corrections to capture practice and quality, so that a review on this is possible. Internal discussions are currently underway around a thematic review of reports of concern sent to Oranga Tamariki.

What this means in practice and what we’ll look for in another 12 months

When we next review progress we will look to understand how changes to the relationship agreement are facilitating better working between the agencies and better outcomes for tamariki and whānau. We will also look to understand what changes Corrections has seen as a result of the revised Immediate Needs Assessment forms, and how this information is being used to support better outcomes for tamariki and whānau. Lastly, we will look to understand trends in the data captured by Corrections around reports of concern and how this is being used.

The Ministry of Social Development () review primarily focused on its interactions with Ms Barriball. This included the provision of both main benefit assistance and emergency housing support.

The review identified that Ms Barriball was receiving a type of case management targeted at families who have high and complex needs, such as family violence, drug and alcohol abuse, debt, health problems, criminal activity, unemployment, housing and education. It noted that all required documentation was provided to meet the criteria for the assistance MSD provided. The review also notes that Malachi was seen by MSD staff in the Tauranga Work and Income office with Ms Barriball, but there were no indications of safety concerns on these occasions. This is why MSD did not contact Oranga Tamariki in relation to Malachi.

The review, dated October 2023, identified initiatives that MSD planned to undertake to improve child protection practices, in line with its Child Protection Policy.

Initiative one

A review and refresh of MSD’s existing MAP (Manuals and Procedures26) and its Doogle (intranet) pages to ensure the information available to staff is clear, relevant and current.

Status: Not achieved

Initiative two

Delivering existing training on MSD’s Child Protection Policy to staff in the next year, and frontline-focused training to be adapted for non-frontline staff.

Status: Not achieved

Initiative three

Increasing the visibility of the Child Protection policy and all the related resources through the various staff platforms on the MSD intranet.

Status: The Ministry of Social Development advise this action is complete

Although work is underway, two of the three initiatives the Ministry of Social Development set for itself are not yet achieved.

MSD told us it has recently refreshed its ‘Child Safe’ online learning module for staff. This covers topics of child abuse and how to recognise and report abuse. The training now covers high-level information about information sharing provisions as set out in section 66C of the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989. The ‘Child Safe’ online learning module is part of MSD’s induction programme, and sets out expectations of how MSD staff should respond when they have concerns about the safety and wellbeing of children. While MSD considers this action is complete, it acknowledges the need to regularly revisit this to ensure that all MSD staff are up to date. It plans to roll out this training as a refresher for all MSD staff later in 2024.

MSD also advised that it continues to improve its operational practices guided by its child protection policy. As part of its commitment to building staff capability in this area, all client facing managers will be undertaking a half-day Family Violence Awareness training between March and July 2024, facilitated by a specialist Family Violence response provider. These training sessions will be made available to all MSD staff throughout the country, later in 2024.

The MSD review also identified that process improvements could be made regarding the report of concern pathway. MSD has discussed with Oranga Tamariki officials the importance of Oranga Tamariki staff ‘closing the loop’ with MSD as frontline staff do not always know whether any action has been taken when a report of concern is lodged. The review noted that understanding the outcome of a report of concern may help encourage frontline MSD staff to be more proactive in raising concerns. This is also consistent with section 17(1)(c) of the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, which notes that:

unless it is impracticable or undesirable to do so, as soon as practicable after a decision is made not to investigate or the investigation has concluded, inform the person who made the report—

-

- whether the report has been investigated; and

- if so, whether any further action has been taken.

What this means in practice and what we’ll look for in another 12 months

In our next review, we will be looking to understand from frontline MSD staff, whether the training and information provided to them is helping them to identify and respond to potential child abuse.

The Ministry of Education commenced a review in May 2022, focused on the actions of Abbey’s Place Childcare Centre while Malachi was in its care.

The review found that the child protection policy in place at Abbey’s Place met the requirements under the Children’s Act 2014, and that there was a procedure that set out how the service would identify and respond to suspected child abuse and/or neglect. However, the review found that Abbey’s Place had not followed its policy or procedure and did not take reasonable steps to consider whether the information available to it indicated there was a risk to Malachi’s safety. Further, effective governance and good management practices were not demonstrated in relation to this.

A provisional licence was issued to Abbey’s Place in May 2022 with conditions the centre needed to meet outlined in a plan. The centre was given until 22 July 2022 to provide evidence of meeting the conditions of the plan. After considering the evidence provided by the centre, a preliminary decision was made to issue a Notice of Intention to Cancel (NIC) the centre’s licence. This was because two of the conditions specified in the provisional licence had not been complied with by the date specified.

In September 2022, the Ministry of Education made recommendations for how it could use lessons from its review of Abbey’s Place, as follows.

Recommendation one

Change Ministry of Education internal processes for decision making on cases where a child has experienced serious harm so that decisions are passed through and approved by the relevant Hautū (Deputy Secretary) of each region, in consultation with the Hautū of Te Pae Aronui (Operations and Integration).

Status: Not achieved

Work on improving processes has started but approval of the draft Framework for managing incident notifications has been delayed due to the changes within the Ministry of Education and the development of Te Mahau27. Before final approval the Ministry of Education needs to consult with persons within the regions who have the delegations to make decisions. The Ministry of Education was not able to confirm when the framework is expected to be finalised.

The Ministry of Education provided information on how its staff manage incident notifications from an ECE service. While this does not incorporate a pathway of notifying the Secretary for Education, we were advised that employees exercise discretion based on a risk assessment to escalate matters on a case-by-case basis. Escalation can go as far as the Secretary for Education when considered necessary.

The Ministry of Education advised that it is monitoring incidents logged on its Takiwā (regions) work management systems to ensure any high-risk situations are escalated to the appropriate Deputy Secretary.

Recommendation two

The Early learning Operations Group within Te Pae Aronui28, in conjunction with Takiwā Hautū (Deputy Secretary Regions), uses what it has learned through the review of Abbey’s Place Childcare Centre following the death of Malachi Subecz to inform regulatory work, including:

i. a current state assessment of how it monitors safety checking and child protection policies to make recommendations for change

Status: The Ministry of Education advise this action is complete

ii. the delivery of a blueprint for being a modern regulator as part of the Te Mahau work programme, including the development of specific recommendations for ECE regulator practice

iii. the establishment of an education sector regulatory group for agencies with regulatory accountabilities for education.

Status: Not achieved

A current state assessment of safety checking in the schooling and early learning sectors (in response to (i.)) was completed in September 2022. The assessment covered the regulatory framework for safety checking and the Ministry of Education’s current practice within the safety checking system. It also identified risks and opportunities for improvement. The intention at the time was to establish a working group that would review the current state assessment and make any recommendations.

In response to (ii.) the Ministry of Education advised that a design team from within Te Pae Aronui have worked to develop a first iteration of a Te Mahau modern regulator approach roadmap. However, this work needs to be developed further with more regulatory rigour before it can be progressed. This work sits within the broader context of the child protection work across the Ministry of Education. The Ministry further advised us that there is no fixed timeframe for this work, which has been affected by its savings programme, and may be further impacted by the Government’s planned ECE regulation sector review.

In response to (iii.) the Ministry of Education advised that staff from Te Pae Aronui completed a stocktake of child protection related responsibilities and activities across the Ministry. This has informed a process to identify gaps and better align and co- ordinate this work.

The Ministry of Education advised that the network and regulatory team within Te Pae Aronui have been working on a strategic plan that will support teams to work together to modernise tools and approaches to regulation in both the schooling and early learning sectors. While work is underway, there is more to be done before the Ministry can commit to the education sector regulatory group.

There are also currently multiple cross-agency groups that meet regularly to progress child protection issues, such as Te Kāhu group working on Core Worker Exemptions. This work has led to increased awareness of gaps in the system and has since resulted in the Ministry of Education’s first investigation into a situation where a worker did not have a core worker exemption.

What this means in practice and what we’ll look for in another 12 months

There has been little progress made towards the recommendations. Changes to internal processes so that where a child has experienced serious harm, licensing and other decisions are overseen by a deputy secretary have not been finalised, and consultation on the draft process still needs to occur. We asked the Ministry of Education when this was expected. On 30 April 2024 it replied that this is in progress and due to be presented to deputy secretaries in April 2024.

Regulatory change work is still at a preliminary stage, with only a current state assessment of safety checking in the schooling and early learning sectors complete to date. Furthermore, the Ministry of Education advised that regulatory change work in respect of child protection will be a continuing area of focus.

When we next review progress we will be looking to see whether the draft framework for managing incident notifications has been finalised and whether and what difference this is making to decision-making. We will also be looking to see if the changes to modernise tools and approaches to regulation have been progressed, and to understand whether and what difference those changes are making to how the early learning sector responds to identify and respond to abuse.

The Office of the Chief Social Worker’s practice review identified that the NZ Police were involved following a ‘breach of peace’ incident that occurred between four adults on 15 October 2021, one of whom was Ms Barriball. The NZ Police then conducted a welfare check on Ms Barriball at her property. Ms Barriball spoke with the NZ Police outside of the cabin she lived in with Malachi, where she confirmed for NZ Police that she and her partner had argued. The curtains were closed and Police did not enter the cabin as they were not aware that Malachi was living there. Because of this the NZ Police did not check on him or provide any information about the incident to Oranga Tamariki. NZ Police later retrieved CCTV footage of the breach of peace incident and identified that Ms Barriball had been assaulted by her partner and recorded this as a family violence incident.

The NZ Police completed a Police Family Violence Death Review (PFVDR) following Malachi’s death in November 2021. A PFVDR is completed following an unnatural death where the suspected perpetrator is a family or extended family member, caregiver, intimate partner, previous partner of the victim, or previous partner of the victim’s current partner. The purpose of a PFVDR is ultimately to assist in the understanding and prevention of future family violence deaths and identify any required changes in policy, practices, and procedures. The PFVDR did not include information on the breach of peace incident they were involved in with Ms Barriball or any information on how this was managed by the NZ Police.

The PFVDR provides a chronological account of events from when Malachi’s mother was arrested through to when Malachi died, including a list of the injuries found on Malachi by hospital staff.