The Poutasi report noted the childcare centre Malachi attended had a policy requiring the reporting of child abuse but did not follow it although it had documented concerns about him. It said that, across professional groups, the reporting and feedback process is not well understood, and it is therefore likely that harm and abuse is under-reported.

Critical gap 4

There is a lack of reporting of the risk of abuse by some professionals and services

The Poutasi report made three recommendations aimed at closing this critical gap. Two recommendations focused on the introduction of mandatory reporting and on training to support professionals mandated to report concerns. The third recommendation focused on monitoring how well ECE services are implementing their required child protection policies to ensure they are providing effective protection for .

Also relevant to this critical gap are findings from the reports by and the Office of the Inspectorate for Corrections. The MSD report recommended that it deliver training on its child protection policy to its kaimahi.35 The Office of the Inspectorate recommended that Corrections review and refresh its processes in cases where there is a report of concern about a child and that, as part of this, it engages with key agencies, including Oranga Tamariki and Police.36

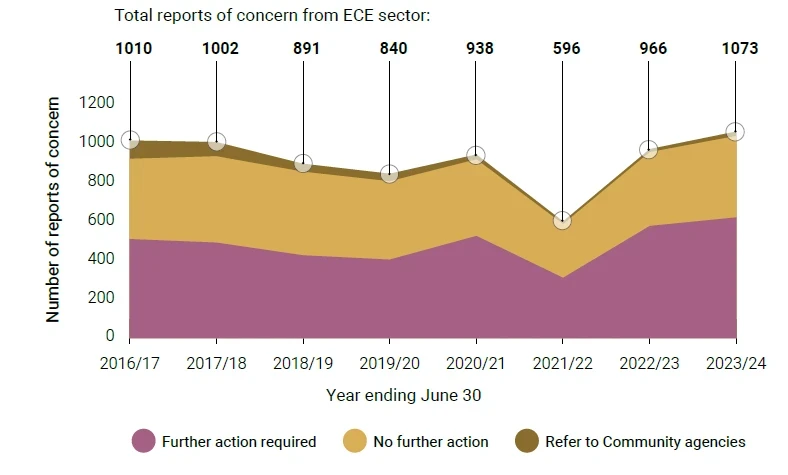

At the time of the Poutasi report, reporting by professionals was at one of its lowest points.

In our 2024 review, we stated that around 80,000 reports of concern were received annually for around 58,000 – approximately 5 percent of the population aged under 18 in . We referenced analysis by Oranga Tamariki that showed reports of concern had been decreasing since 2017/18, particularly from professional and government notifiers. Our 2024 review noted that this showed signs of increasing again from 2022/23 – after the publication of the Poutasi report.

The Government recently announced that it will progress towards a mandatory reporting regime with a stepped approach. As a first step, it will introduce mandatory child protection training for designated workforces. This is to ensure that those workforces have the knowledge and capability required to report suspected abuse of tamariki and .

In the meantime, some children’s agencies have already provided training for their kaimahi working with tamariki and rangatahi on when to report concerns. Accordingly, reports of concern from professionals have increased. The work that the Government is planning will further support and strengthen reporting, but the gap that needs to be addressed is how Oranga Tamariki responds to the reports of concern it receives, which we discuss later in this report.

As part of the stepped approach the Government announced, it noted that children’s agencies’ systems and Corrections’ systems will need to be bolstered so that, when mandatory reporting comes into effect, those systems are ready and able to respond in a timely way.

Since our 2024 review, the ECE regulatory sector review37 has been completed. One of its recommendations was to amend ECE licensing criteria to strengthen how services must evidence how they have implemented their child protection policies and procedures. These changes will enable ERO and the Ministry of Education to assess whether ECE kaimahi are prepared and able to respond to child protection policy-related matters.

The revised licensing criteria are expected to be implemented in April 2026. The Ministry of Education and ERO told us they have been working with the ECE sector to promote a greater awareness and understanding of child protection requirements. This may be having a positive impact as fewer instances of non-compliance with child protection requirements were identified in 2024. Our engagements with ECE services also identified a consistently good understanding of their child protection policies and how to make a report of concern to Oranga Tamariki.

Some reviews of child deaths by both Oranga Tamariki and Police point to a need for more knowledge and education about child abuse and reporting. PFVDRs, in particular, identify a need for more and better education for agencies and the public.

“Enhanced education of the community, other agencies, and Police regarding the effects of mental health, family violence, identifying warning signs and how to report and where to report this information is imperative for prevention.” POLICE CHILD DEATH REVIEW

One of the PFVDRs for a child aged under 1 identified that several people were concerned about the safety of the child. Two people, on two separate occasions, witnessed the child being shaken by their parent. Neither person made a report of concern or disclosed their concerns to any agency. This child died of a traumatic head injury, and their parent was charged with their murder. The PFVDR notes that one person who saw the child being shaken said that reporting to Oranga Tamariki is “pointless”, as they had previously made a report of concern (about the child’s sibling) and “no action was taken”.

Existing provisions in the Oranga Tamariki Act in section 7(2)(ba)(i) and (ii) place duties on the Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki to:

- educate both the public, and professional and occupational groups, on how to identify, prevent and report cases of child abuse

- develop and implement protocols for government agencies and and professional groups related to reporting child abuse.

We asked Oranga Tamariki if it had a strategy for fulfilling these requirements and what groups, if any, it had worked with since 1 July 2024 to do that. Oranga Tamariki told us it does not have a strategy for regular public campaigns to raise awareness of child abuse. It did not tell us whether it had worked with any professional groups over this period. It noted it regularly publishes research, evaluation and insights reports related to the wellbeing of , and and the social services sector on its website.

When we asked Oranga Tamariki how it worked with ECE services as part of our last review, it told us this was not its responsibility.

In October 2025, the Government told us that it has committed to a public campaign to increase awareness of the signs of abuse. This will directly respond to a recommendation in the Poutasi report that regular public awareness campaigns should be undertaken so the public is attuned to the signs and red flags that can signal abuse and are confident in knowing how to report this, so tamariki can be helped.

The impact of not educating professionals and the public about when to make reports of concern can be seen on the ground. Oranga Tamariki social workers told us they are frustrated that Oranga Tamariki is viewed as the default agency to provide support to tamariki, rangatahi and their whānau and that reports of concern from other agencies do not always meet the threshold for statutory intervention.

“I found many [reports of concern from a community reports of concern table] don’t require [a family group conference], so we pile up [Oranga Tamariki] social work caseloads. The perception [from the table] is it sounds too hectic – for example, meth use or family harm – then it becomes [Oranga Tamariki] work … I’ve been here 14 years, that could sit with community.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

Some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi said other agencies could sometimes do more to support tamariki, rangatahi and whānau instead of making a report of concern.

“Sometimes [mental health agencies] know we have the power [to uplift]. For tamariki/rangatahi with mental health that is out the gate, they know we can uplift the children. We get that side, but we are not mental health professionals.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

We heard from some health kaimahi that the Oranga Tamariki hospital liaison helps them to make reports of concern by ensuring complex health information is presented clearly and simply. It is not clear, however, whether this approach supports an improved Oranga Tamariki response to these reports of concern.

The Government is also working to improve child protection knowledge, skills and training for professionals who work with tamariki and rangatahi

The Poutasi report made two recommendations focused on improving the reporting of concerns about tamariki by professionals. In particular, it recommended that professionals who work with tamariki and rangatahi should be mandated to report suspected abuse to Oranga Tamariki. It said that this should be legislated by defining the professionals and service providers who are to be classed as ‘mandatory reporters’ to remove any uncertainty around their obligations to report.

In addition, the Poutasi report recommended that the introduction of mandatory reporting should be supported by a package approach that includes:

- a mandatory reporting guide with a clear definition of the red flags that make up a high-risk report of concern, together with the creation of a ‘high report of concern’ category similar to the New South Wales ‘risk of significant harm’ definition

- defining mandatory reporters, all of whom should receive regular training

- for professionals deemed to be mandatory reporters, undergraduate courses teaching risks and signs of child abuse and mandatory regular updated training regarding their responsibilities and the detection of child abuse, with practising certificates conditional on training and refreshers.

Our 2024 review noted it is not clear what impact mandatory reporting would have in . We noted that child protection systems in the similar Australian jurisdictions of New South Wales and Victoria had become overwhelmed following the introduction of mandatory reporting. We further noted that we had heard Oranga Tamariki was struggling to address the number of reports of concern it received.

We concluded that, in the context of the recommendation to introduce mandatory reporting, we saw two apparent options:

- Further resource/reprioritise existing funding within Oranga Tamariki (and take opportunities to streamline processes and remove duplication) and improve funding for community organisations.

- Improve education and training for professionals and service providers around the identification and reporting of child abuse.

In October 2025, the Government announced that it would progress towards a mandatory reporting regime with a stepped approach. First, mandatory child protection training will be introduced for designated workforces to ensure that those designated workforces have the knowledge and capability required to report suspected abuse of tamariki and rangatahi. Concurrently, the Government intends to better resource the systems of children’s agencies and Corrections so that, when mandatory reporting comes into effect, those systems are ready and able to respond in a timely way.

As we detail below, professionals are reporting concerns to Oranga Tamariki. We welcome additional training and resource for the child protection system, and if implemented well, this should help keep tamariki safe. It should also reduce some of the unintended consequences associated with mandatory reporting. Additionally, increased reporting also requires Oranga Tamariki to be in a position to respond when needed. Later in this review, we note that Oranga Tamariki is struggling to respond to the current demand.

A relationship with Oranga Tamariki would help ECE services identify signs of abuse and know when – and how – to report concerns

ECE services have a crucial role in identifying suspected abuse or neglect of tamariki. For this review, we were interested in how well ECE services understand when and how to report concerns and what processes they have in place to help them do this.

ECE kaimahi had a limited understanding of the Oranga Tamariki role and when it would intervene. The ECE services we heard from rarely had a relationship with their local Oranga Tamariki site. Where there was a relationship, it appeared to have arisen as a result of ECE kaimahi working with Oranga Tamariki social workers to support particular tamariki rather than intentional relationship building.

“Certain [Oranga Tamariki] sites are better than others. Not even just the site – it could be that one social worker. If you get a great social worker then you are in, you can work collaboratively, then other times no.” ECE LEADER

Some ECE kaimahi told us they appreciated receiving guidance when they contacted Oranga Tamariki about whether an immediate report of concern was warranted.

Based on what we heard from ECE kaimahi, it is clear they would value having a relationship with their local Oranga Tamariki site that could support them with decisions on whether to make a report of concern.

All ECE kaimahi we met with told us about training they had within the ECE sector to help them identify child abuse. All of them described the requirements of their centre’s child protection policy and when they would make a report of concern.

All ECE kaimahi we heard from talked about using collective decision making to determine whether to lodge a report of concern with Oranga Tamariki. They told us this included having ways to raise concerns within their organisational structure to leadership and governing bodies. For example, kaimahi from kōhanga reo and kindergartens spoke about referring cases to governing bodies if it was not clear whether a report of concern to Oranga Tamariki was warranted.

Kaimahi from the independent ECE services we met with talked less about their organisational support networks than others but still told us that the decision to make a report of concern would be made between ECE kaimahi and leadership.

In a couple of ECE services, we heard that staffing ratios were problematic if kaimahi need to lodge a report of concern.

“Because we work to ratio, we can’t leave the floor during the day when the are here. This means we can’t call Oranga Tamariki to make a report of concern until after the tamariki have left. This is worrying for us as they may be returning to where there is harm occurring, but our policy is that we can’t go below ratio.” ECE KAIMAHI

“There’s only one number to call [Oranga Tamariki] and that can be crazy busy.” ECE KAIMAHI

However, kaimahi from one ECE service said that, if required, they would go under ratio to lodge a report of concern.

“If a child was in immediate danger and teacher had to leave, we just throw the ratios out the window. Then we talk to the [Ministry of Education] on why we did that.” ECE LEADERSHIP

We heard that, when ECE kaimahi make a report of concern, they are also thinking about maintaining relationships with . However, ECE kaimahi acknowledged that the safety of tamariki outweighed worries about how whānau would react if they knew the ECE had made a report of concern. They worry that, if the whānau remove their child from the centre, not only is that child’s safety now less visible but the whānau may have lost an important support and become more vulnerable.

“In one case we reported, the family realised what was happening so they dropped everything and moved to another country. When we think about it, we get sad about that and those children.” ECE LEADER

“The biggest worry is that we lose the child [the child will be taken away by whānau or won’t return to the centre] and we have to put that [idea] aside because safety is more important than losing a child.” ECE LEADER

“If you ring Oranga Tamariki, you have got to be sure as you don’t want to upset the family as they need support from somewhere.” ECE LEADER

Reports of concern from ECE kaimahi have increased in the past two years

All ECE services told us their practice was to report concerns to Oranga Tamariki where they felt the concern met the threshold. The ECE services who told us they had not made a report of concern recently said it was because they were confident there had not been a need.

Our 2024 review noted that reports of concern from kaimahi at ECE services were at their lowest at the time of Malachi’s death but were starting to increase.

The Ministry of Education and ERO told us they had publicised the Ministry of Education’s child protection training module to the sector, and this had led to an 85 percent increase in the number of people completing the module in 2023. They said they promoted and supported greater awareness about how to report child protection and safety concerns and had developed and shared a clearer understanding of the roles and responsibilities of key agencies in this.

While a higher number of reports of concern from ECE services are being progressed for further action by Oranga Tamariki than in previous years, the proportion of reports of concern where further action is taken has not changed (Figure 1). It is unclear whether this is because there has been no change in the understanding of when to make a report of concern, despite the training, or if it is because of Oranga Tamariki resourcing and decision making.

Figure 1: Despite the number of reports of concern from ECEs fluctuating, the proportion where Oranga Tamariki takes further action has not

told us it has completed three actions it set for itself that were designed to improve the knowledge of its kaimahi around how to recognise and report child abuse. As well as ensuring information available on child protection is clear, relevant and current and increasing the visibility of its child protection policy and related resources, MSD has delivered its ChildSafe online learning module to kaimahi.

MSD told us that, as of 3 June 2025, 98 percent of its kaimahi38 had completed the ChildSafe online learning module, which covers how to recognise and report child abuse and includes content about the information-sharing provisions in the Oranga Tamariki Act.

To determine whether the training was helping MSD kaimahi identify and report potential child abuse, we surveyed 65 MSD integrated services case managers in five regions (Northland, Bay of Plenty, Central, Canterbury and Southern) in June 2025. The survey targeted this frontline role as it supports clients with complex needs who may be more vulnerable and at risk of harm and therefore more likely to make reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki. We received responses from 46 of the 65 MSD kaimahi.

The survey responses indicate that the training has been helpful and is being used by MSD integrated services case managers in their work. Full results from the survey can be found at Appendix C.

Data from Oranga Tamariki on reports of concern shows a slight increase in the number of reports of concern made by MSD over the last two years that resulted in a further action decision (Table 2).

While we cannot say whether this increase is related to the rollout of the MSD ChildSafe training, the survey results indicate that a higher proportion of respondents who had completed this training had made a report of concern compared to respondents who had not done the training (or were unsure if they had). As the difference is not statistically significant and the number of MSD kaimahi surveyed is small, it is not clear whether the training and education about child protection has increased awareness and reporting of concerns.

| 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reports of concern from MSD kaimahi that resulted in a further action decision | 122 | 132 | 140 |

MSD told us insights from the survey would inform future training modules and content aimed at keeping safe.

The Poutasi report recommended that there should be active monitoring of implementation by ECE services of their required child protection policies to ensure they are providing effective protection for . It said the Ministry of Education and ERO should jointly design and administer a monitoring and review cycle for the implementation of child protection policies in ECE services.

Our 2024 review identified that ECE services are required to have a written child protection policy,40 review their policy every three years and have a procedure for safety checking all children’s workers.41 Data provided by ERO for our 2024 review showed it had identified an increase in non-compliance with these legislative requirements between July 2022 and December 2023.

Corrections advised that the Prison Operations Manual includes guidance on making reports of concern. It told us it updated the learning pathway for probation officers in January 2025, which includes a module on Corrections’ child protection policy, child protection obligations for probation officers, types of abuse and the process to make a report of concern.

Corrections said that, from January 2025, all probation officers who join the agency would be required to complete this module. Corrections is also creating an all-of-organisation learning module on its child protection policy and kaimahi responsibilities.

Corrections has used REFER online since 2021/22 to send reports of concern. Because of this, Corrections is the only agency other than Oranga Tamariki that has a centrally held record of when a report of concern has been made, by whom and the site. Corrections told us that most of its reports of concern are made by probation officers. The number of reports of concern made by prison-based kaimahi is low, peaking at only 12 in the 2024/25 year.39

Corrections data shows an increase in the number of reports of concern made and suggested that this increase may indicate improved awareness following the training and information it has disseminated to its frontline kaimahi (Table 3).

| 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total reports of concern recorded by Corrections as being made by Corrections kaimahi | 202 | 278 | 470 | 605 |

| Total reports of concern recorded by Oranga Tamariki as being made by Corrections | 1,382 | 1,177 | 1,095 | 1,254 |

* The data for 2024/25 is for the nine-month period from 1 July 2024 to 31 March 2025 so is an incomplete year.

Data also shows that a greater number and larger proportion of reports of concern recorded by Oranga Tamariki as from Corrections were progressed to further action in 2023/24 compared to 2022/23 (Table 4). We cannot say for certain whether this increase is due to the training, but it may indicate that the training has enabled Corrections kaimahi to better identify and report on the cases requiring action.

| 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reports of concern recorded by Oranga Tamariki from Corrections kaimahi that resulted in a further action decision | 473 | 476 | 490 |

Data provided by Oranga Tamariki shows a higher number of reports of concern made by Corrections kaimahi than indicated by Corrections. When we asked about this discrepancy, Corrections told us its kaimahi use REFER online to send both reports of concern and information-sharing notifications when people leave prison. Oranga Tamariki records all of these notifications as reports of concern, which is why the data is different. Corrections confirmed that it does not count information-sharing notifications as reports of concern.

Corrections and Oranga Tamariki further advised that a small number of reports of concern from Corrections kaimahi are made by phone, with 10 recorded by Oranga Tamariki between 1 January and 2 October 2025. Corrections said it is possible there could also be other reports of concern that have not been captured in its data and that it plans to look into this further.

Corrections also told us about work it has been doing to progress the recommendation of the Office of the Inspectorate to review and refresh processes in cases where there is a report of concern about a child. It told us that all material on its intranet on child protection has been reviewed. Updates are being made to ensure the information is easy for kaimahi to find and clear to follow.

Guidance is being developed for kaimahi on what a good-quality report of concern looks like and what information to include. Corrections has worked with Police and Oranga Tamariki regarding the processes for reporting concerns and this is informing the development of updated material and guidance, which is expected to be available to kaimahi by December 2025. The updated materials and guidance are intended to support Corrections kaimahi who are concerned about the safety of a child to know how to make a report of concern and what information to provide.

In our 2024 review, we noted that Corrections was considering undertaking a thematic review of reports of concern made to Oranga Tamariki. For this review, Corrections advised that this has not been progressed but will be reconsidered once the updated guidance and all-of-organisation child protection policy learning module has been implemented.

The Poutasi report recommended that there should be active monitoring of implementation by ECE services of their required child protection policies to ensure they are providing effective protection for . It said the Ministry of Education and ERO should jointly design and administer a monitoring and review cycle for the implementation of child protection policies in ECE services.

Our 2024 review identified that ECE services are required to have a written child protection policy,40 review their policy every three years and have a procedure for safety checking all children’s workers.41 Data provided by ERO for our 2024 review showed it had identified an increase in non-compliance with these legislative requirements between July 2022 and December 2023.

We reported that the Ministry of Education and ERO told us they were finalising a work plan to strengthen the review cycle and enhance and support child protection in ECE. We noted that the Ministry of Education and ERO had undertaken work to understand barriers to the ECE sector making reports of concern. The Ministry of Education’s child protection training module had been promoted, which had led to an increase in the number of ECE kaimahi completing the module.

Our 2024 review noted that some of the changes to strengthen ERO’s review cycle were dependent on regulatory change, which was being progressed through the ECE regulatory sector review. The ECE regulatory sector review has since been completed.

One of the recommendations of the regulatory review was to amend ECE licensing criteria to strengthen how services must evidence implementation of their child protection policies and procedures. The changes will enable ERO and the Ministry of Education to assess whether ECE kaimahi are prepared and able to respond to child protection policy-related matters.

The Ministry of Education consulted with the ECE sector on the proposed amendments in June and July 2025, with the changes progressing through the introduction of the Education and Training (Early Childhood Education Reform) Amendment Bill in July 2025. The revised licensing criteria were gazetted on 28 November 2025 and are expected to be implemented in April 2026. This lead-in time gives the ECE sector and the Ministry of Education time to prepare and train kaimahi on the changes.

Recent data from ERO and the Ministry of Education suggests compliance with ECE child protection requirements may have improved between 2023/24 and 2024/25. Data from ERO shows a significant decrease in non-compliance related to safety checking in ECE services in the 2024/25 year compared to 2023/24 (Table 5). There was also a more modest decrease in concerns about compliance with child protection policies.

| 2023/24 | 2024/25 | |

|---|---|---|

| Safety checking non-compliance | 173 | 46 |

| Child protection policy non-compliance | 33 | 24 |

ERO told us that, throughout 2024, it helped services understand their obligations and improve their practice in relation to child protection requirements. This included clarifying requirements, supporting services’ implementation of child protection policies and introducing a new reporting format for English-medium licensed ECE services in July 2024. It has also continued to focus on training and supporting staff with guidance and resources to understand their role in relation to child protection.

While not directly comparable,42 data from the Ministry of Education also shows a decrease in non-compliance relating to child protection in licensed ECE services between 2023 and 2024. Table 6 shows the decrease in the number of provisional licences43 issued because of non-compliance with child protection requirements.

| 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| Provisional licence for non-compliance with safety checking | 79 | 25 |

| Provisional licence for non-compliance with child protection policies | 56 | 18 |

Similarly, from 2023 to 2024, there was a decrease from three to one for licence suspensions for non-compliance with child protection policies and a decrease from 38 to 16 for suspensions for non-compliance with safety checking.

The Ministry of Education told us it has continued to promote awareness of resources and training on child protection to the ECE sector. It told us that there had been a further increase in the number of ECE kaimahi who completed the Ministry’s child protection training last year – from 7,291 in 2023 to 8,319 in 2024. ECE kaimahi also told us they were accessing the Ministry of Education training.

Larger ECE service providers with multiple licensed services told us they had created and delivered their own child protection training in addition to the Ministry training.

The actions taken by ERO and the Ministry of Education may be contributing to improved compliance in the ECE sector. As we only have data and information to compare between 2022 and 2024 and most ECE services are reviewed by ERO on a three yearly cycle, it is too early to comment on whether this is a sustained shift in the sector – but it is promising.

35 msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/information-releases/msd-childprotection-policy-practice.pdf

36 See footnote 33.

37 Ministry for Regulation. (2025). Early Childhood Education (ECE) regulatory sector review.

regulation.govt.nz/regulatory-reviews/early-childhood-education-ece-regulatory-sector-review/

38 This percentage represents 8,921 kaimahi having completed the training out of a total 9,089.

39 This data is for the nine-month period from 1 July 2024 to 31 March 2025. It was also the highest number of reports of concern from Corrections kaimahi across the four years of data that Corrections provided us.

40 For most licensed services, the requirement is: “There is a written child protection policy that meets the

requirements of the Children’s Act 2014. The policy contains provisions for the identification and reporting of child abuse and neglect, and information about how the service will keep children safe from abuse and neglect, and how it will respond to suspected child abuse and neglect. The policy must be reviewed every three years.” Ministry of Education. (2024). Child protection. education.govt.nz/education-professionals/early-learning/licensing-and-certification/licensing-criteria-for-centre-based-ece-services/health-and-safety/child-protection

41 Children’s workers are defined in the Children’s Act.

42 The Ministry of Education and ERO data cannot be directly compared as it does not relate to the same services. and the actions taken by the Ministry of Education may be in subsequent years to ERO’s reviews. For this reason, the numbers do not align and should not be directly compared

43 The Ministry of Education has the statutory powers to intervene when services breach the regulated standard. If services are non-compliant with child protection requirements, the Secretary for Education is able to decide depending on the level of risk to children to issue a provisional licence or a suspension notice. A provisional licence allows a service to continue operating while remedying the non-compliance as opposed to suspension, which stops the service from operating from an effective date.