Responding to reports of concern

The primary focus of the Poutasi report was on how to better identify harm or the risk of harm and to make sure that Oranga Tamariki and other agencies had access to the best information to keep safe.

The Poutasi report looked at the circumstances surrounding the death of Malachi and considered previous child death reviews. However, it did not specifically look at the ability of the care and protection system to respond once a report of concern is made.

Our 2024 review found that, when people report concerns, the response from Oranga Tamariki was not sufficiently focused on the safety of the child. Decisions of Oranga Tamariki social workers were unduly influenced by available resource, with differing thresholds for intervention between regions and sites. At times, decision making gave greater weight to the voice of , with the need and safety of tamariki secondary.

Overall, we found that did not yet have a comprehensive child protection system that consistently responds in a way to either keep tamariki safe or to support whānau to prevent harm from occurring.

This review shows that little has changed. There continues to be a high proportion of reports of concern from professionals that do not result in further action by Oranga Tamariki and where tamariki and are not seen. Kaimahi from agencies and services, including Oranga Tamariki, continue to tell us they are concerned about the risk to tamariki and rangatahi.

System settings have not changed, gaps remain and tamariki and rangatahi are still no more likely to be seen by Oranga Tamariki now than when Malachi was killed.

Implementing the Poutasi recommendations may make tamariki and rangatahi at risk more visible, but to make them safer, Oranga Tamariki and the wider child protection system must be able to respond when needed.

Oranga Tamariki is looking for reasons not to intervene rather than getting in the car to visit tamariki when serious concerns are raised

In our 2024 review, we found that actions taken had not contributed to the system-wide change envisaged by the Poutasi report. There was a lack of clarity about the statutory role of Oranga Tamariki, the appropriate threshold for its intervention and its ability to respond to reports of concern.

Progress with the Poutasi recommendations is slow. Better visibility and reporting of concerns are important but can only go so far. Even once all the recommendations have been implemented, it would not solve the fundamental problem – Aotearoa does not yet have a child protection system that is always able to respond when needed. In fact, increased reports of concern may have the unintended consequence of placing more pressure on a system already struggling to respond.

Social workers want to keep tamariki and rangatahi safe – and they often do – but the current child protection system is not always keeping children safe. There are several reasons.

- Oranga Tamariki is overwhelmed by the high numbers of reports of concern it needs to assess and respond to.

- People who have made a report of concern do not hear back from Oranga Tamariki and remain concerned about those tamariki and rangatahi. This can result in additional reports of concern being made, which further overwhelms the system.

- Despite a standardised approach to assessing reports of concern and quality assurance processes, Oranga Tamariki decisions on whether to intervene are unduly influenced by site resources. As a result, thresholds for intervention vary across sites and regions.

- Decisions by Oranga Tamariki sites on whether to intervene are not always child-centred.

- Social workers do not all have the skills they need to assess risk, and induction and training are not meeting this need.

- There is not always the resource or capability within Health NZ to help social workers assess risk and harm.

- The threshold for Oranga Tamariki to take action is too high.

- Oranga Tamariki is continuing to refer tamariki and rangatahi to stretched community providers although it knows they have limited capacity to provide the support needed.

Oranga Tamariki data shows the number of reports of concern is increasing, although this is not necessarily indicative of increased harm in our communities.

Oranga Tamariki notes that changes in public awareness and reporting behaviours are driving some of this increase. It suggests that increases in actual harm and wellbeing concerns driven by social and economic issues are also a factor.49

Changes in the way that Oranga Tamariki records reports of concern and an increase in renotifications for and already known to Oranga Tamariki also explain some of the increase, as we discuss below.

Between 2017/18 and 2021/22, total yearly reports of concern decreased by 28 percent to 66,400 reports of concern about 49,300 tamariki and rangatahi. However, the most recent data provided to us by Oranga Tamariki shows total yearly reports of concern increased by 44 percent between 2023/24 and 2024/25 to 108,100. The number of tamariki and rangatahi who had reports of concern made about them also increased by 17 percent – from 53,100 in 2023/24 to 62,400 in 2024/25.

All notifier types recorded by Oranga Tamariki made more reports of concern in 2024/25 than in 2023/24. In both years, the greatest number of notifications were made by Police and kaimahi in the health and education sectors.

Changes in how Oranga Tamariki records reports of concern and renotifications have contributed to the increase

In the first half of 2024, Oranga Tamariki changed how it records calls to the NCC in response to a recommendation from the Ombudsman.50

All calls that meet the definition of a report of concern are now recorded as a separate report of concern, even if there is already an open report of concern for the same tamariki and rangatahi or if it does not meet the threshold for assessment or investigation. Previously, some of these calls were entered as a contact record or were added as case notes to the existing case file and the social worker notified.

A proportion of the increase can also be attributed to renotifications – where Oranga Tamariki receives more than one notification for the same child about the same concerns.

The Oranga Tamariki analysis shows renotifications have increased over time, but it only looks at renotifications received within a month of the initial report of concern. Given that some professionals may allow much longer than a month for Oranga Tamariki to take action before making a second report of concern about a child, only looking at renotifications made within a month may not show the full picture.

The approach taken to the analysis by Oranga Tamariki makes it difficult to see the extent to which renotifications and the change in recording practices are together driving the increase in total reports of concern.

When considered alongside what we heard in every region we visited and with professionals telling us they are making repeated reports of concern because Oranga Tamariki does not act or does not inform them of any action taken, it is likely that the number of renotifications is being underestimated by Oranga Tamariki.

People who make a report of concern do not always hear back from Oranga Tamariki, resulting in repeated reports of concern and continued worry about the child’s safety

In our monitoring visits we consistently heard from professionals, including health and education kaimahi and police officers, that they are not hearing back from Oranga Tamariki on the outcome of reports of concern they have made. They don’t know whether any action has been taken or if the child is safe. This is despite section 17(1)(c) of the Oranga Tamariki Act requiring Oranga Tamariki to inform the notifier of the outcome of a report of concern.51

“We just don’t know what we’re going to get. You might get no action, you might get a big response.” HEALTH KAIMAHI

This is leading to frustration from kaimahi at government agencies and community organisations.

“We complete [reports of concern]. Go back to families and we can see zero impact, no reach in from Oranga Tamariki.” POLICE LEADER

“We send another report of concern. It’s on repeat, repeat, repeat.” POLICE LEADER

“[Reports of concern] have not been addressed though [by Oranga Tamariki], we just keep advocating.” COMMUNITY AGENCY LEADER

In particularly serious cases, Police and one community organisation told us they escalated follow-ups on their reports of concern to increasingly senior kaimahi in Oranga Tamariki to find out what was happening.

“Kids are running away all the time, and kids are being sexually assaulted every week. And we don’t hear back from Oranga Tamariki. It’s huge work and it’s heartbreaking.” HEALTH KAIMAHI

“We don’t get any feedback from our reports of concern, and we’re not doing it for fun. We keep rolling it through and we don’t hear anything from Oranga Tamariki.” POLICE KAIMAHI

“For [reports of concern] that are severe [and already known to Oranga Tamariki], you get nothing [no communication]. I continuously send things.” POLICE KAIMAHI

We heard health kaimahi often have to “chase up” to find out what action has been taken in response to their reports of concern, and the Oranga Tamariki hospital liaison will help them do this. We heard waiting for Oranga Tamariki is frustrating for , and health kaimahi feel responsible for ensuring tamariki and rangatahi remain safe.

One health kaimahi said they operate on the assumption that making a report of concern acts as a protection. However, when they don’t hear back from Oranga Tamariki, they are unsure what, if anything, has happened, and whether it did provide protection. This lack of communication compounds the worry many organisations have about making reports of concern and how that could impact their relationship with whānau.

“We make a [report of concern], then [Oranga Tamariki] don’t let us know. We think we have provided a bit of safety by reporting this but then we don’t know what happens.” HEALTH KAIMAHI

“There is still an awful amount of concern about making reports of concern and who makes it, and what that means for our relationships, and even what difference will it make, and also what is the outcome that will occur?” HEALTH KAIMAHI

When Oranga Tamariki receives a report of concern, it makes an initial assessment. The NCC completes almost all initial assessments, with a small number made by specific sites.

The initial assessment can include contacting the person making the report of concern, as well as others, to develop an understanding of the needs and vulnerability of the child and to develop a chronology. Decisions made on initial assessments may be:

- that no further action is required

- to refer the child to a community agency for support

- that further action is needed by way of either a child and family assessment or an investigation under the CPP.

Where the initial assessment is made by the NCC and results in a decision that further action is needed, this is sent by the NCC to the Oranga Tamariki site responsible for the area where the child lives for the site to undertake a core assessment.

A core assessment builds on the initial assessment to understand the risk and needs for , and their .

Sites are not bound by the decision of the NCC to take further action. Sometimes, the sites know the tamariki and whānau that the report of concern relates to and have local knowledge that the NCC did not have when making its initial assessment. Accordingly, sites may subsequently decide to overturn a decision made by the NCC and instead refer the child to a community agency or determine that no further action is required.

The NCC uses a standardised approach for initially assessing reports of concern and now has quality assurance processes over decision making

Our 2024 review noted that most initial assessments were completed by the NCC and that this was mostly working well. However, we also noted that, at the time, the NCC did not make quality assurance reports to national office, so there was a lack of assurance over whether its decisions were correct. Also, a small number of sites were completing initial assessments, rather than the NCC, and across these sites, there were different quality assurance processes to check their decisions.

For this review, we asked Oranga Tamariki whether any work had been done to confirm that initial assessment decisions in response to reports of concern are being made correctly. We specifically asked whether there had been any improvements to quality assurance of decision making on initial assessments by both the NCC and sites.

Oranga Tamariki told us that there are now quality assurance processes over initial assessment decisions by the NCC. It told us both the NCC and sites use the Decision Response Tool to support consistent and objective decisions on the appropriate response pathways for reports of concern. Oranga Tamariki said that, while there is a degree of professional judgement in any quality assurance process, it is not aware of any decisions being made on professional judgement alone.

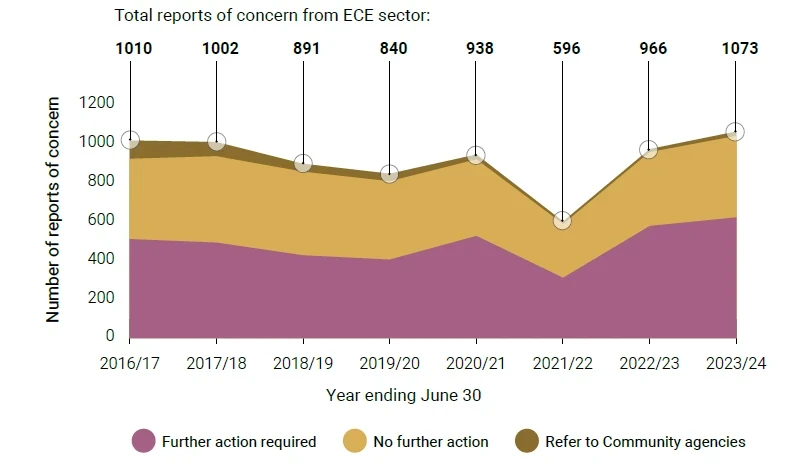

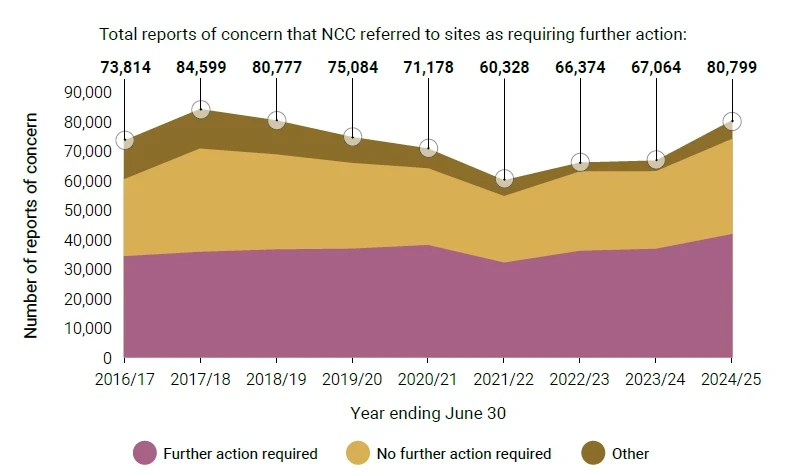

In our 2024 review, we referenced data from 2016/17 to 2022/23 and noted that, of the reports of concern considered by sites, the number of reports of concern that result in further action has remained consistent at around 40,000 each year.

The number of reports of concern that resulted in further action in 2023/24 and 2024/25 appears similar to previous years at 42,800 in 2024/25, despite the increase in total reports of concern (Figure 2). This indicates that site decision making on whether to take action is closely linked to organisational capacity to respond.

Figure 2: Though the total number of reports of concern varies over time, the number resulting in further action has remained steady.

Because of resourcing limitations, a significant number of for whom concerns are reported are not visited. Kaimahi from Oranga Tamariki and Police as well as other professionals tell us the risk to tamariki and is high as a result.

“What has happened is that Oranga Tamariki won’t uplift kids as to bring the statistics down. Oranga Tamariki won’t uplift kids in grave danger … [because of] the perception of Oranga Tamariki in the media, pressure from management. I have been doing Oranga Tamariki work for 30 years, it is more difficult now than ever.” COMMUNITY PROFESSIONAL

“Oranga Tamariki are very quick to surprise lots of police officers. How can you close this [family’s case] from what the police officer has seen? What’s happening?” POLICE LEADER

“If [Oranga Tamariki leadership] had made some of these [restructuring] decisions to keep [tamariki and rangatahi] safer, we could work with that. I know there’s going to be preventable deaths. What annoys me is that social workers will be pinpointed and their supervisors. I can accept when there’s mistakes and poor practice, but [in] the review of the next baby’s death, they won’t be looking at the restructure.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

Sites continue to overturn around half of NCC decisions that further action is required

As in our 2024 review, we looked at Oranga Tamariki data on the proportion of NCC further action decisions accepted by sites (Figure 3). Patterns are much the same, with around half of reports of concern referred from the NCC to sites for further action progressing to further action. This means half of the reports of concern that the NCC determined required further action were overturned at site and no further action was taken.

Figure 3: NCC decisions that further action is required on a report of concern continue to be overturned by sites.

The overturning of NCC decisions results in regional and site variations on the threshold for intervention

Regional variations also mirror what we saw in our last report, with NCC decisions more likely to be accepted in Auckland than in Canterbury and the Upper South (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Regional variation in responding to reports of concern referred by the NCC for further action.

While we acknowledge that Oranga Tamariki cannot control the volume of reports of concern it receives, it can improve processes to better manage the response to those concerns.

For this review, we asked Oranga Tamariki how it ensures sites have the capacity and resources they need to respond to reports of concern and whether it has a strategy for addressing capacity issues. Oranga Tamariki explained that:

- although the increased volumes have made it more difficult to respond quickly and have added to pressure on kaimahi and support systems, it has multiple systems to ensure tamariki and rangatahi with the greatest need are prioritised

- calls to the NCC are screened promptly, so even in periods of high volume, urgent matters are put through to a social worker almost immediately

- it initially assesses urgency, and cases with high urgency, those that involve babies or infants and those that require a joint CPP response with Police are allocated quickly

- roles are sometimes reoriented to support teams or sites under the greatest pressure, and this sometimes includes redeploying kaimahi from other sites in the region or nationally if necessary

- reports of concern with lower risk are not always allocated immediately to avoid placing social workers under undue pressure, and it also has a protocol to review social worker workloads that exceed a set level.

Reports of concern are sometimes delayed getting to sites

In our monitoring engagements with Oranga Tamariki kaimahi, we heard the process of the NCC completing initial assessments was not always working well. We heard that delays in the NCC completing initial assessments and sending reports of concern to sites were limiting sites’ ability to respond due to the age of the reports of concern.

Some Oranga Tamariki site leaders told us there had been significant delays in reports of concern being sent to sites from the NCC, with “over 100 [reports of concern] that were over 22 days old”.

We heard that lack of capacity combined with high workloads was further exacerbating the delays and reducing the ability of social workers to respond appropriately.

Oranga Tamariki continues to not make the best use of the resources it has

Leaders at NCC told us little has improved since we last reported. We heard that changes in recording practice and what they described as “the increasing complexity of reports of concern” has made their work more resource intensive. They explained they are “all fighting for resources” across the organisation.

Leaders at NCC wanted Oranga Tamariki leadership to better define roles and responsibilities between the NCC, sites and multi-agency tables, as this would remove some of the existing confusion and duplication of effort. They also spoke of the need to better resource the “front door” so time can be taken to do thorough initial assessments.

In our 2024 review, we noted “Oranga Tamariki is not making the best use of the resources it has to respond to the number of reports of concern for tamariki, and sites are spending time reassessing further action required decisions made by the NCC”.52 This has not changed.

Even if the initial assessment process is improved, unless frontline social workers are able to properly assess safety by getting eyes on the child, risks will remain

In one region, we heard that, despite public assurances that frontline services would not be affected, the Oranga Tamariki restructure had reduced frontline staffing and resourcing.

We heard some site leaders were carrying caseloads, that youth justice kaimahi were picking up work for care and protection kaimahi and that there was a freeze on hiring new staff. Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us they must choose which cases to work on and which to leave.

“As leaders, we take a workload as well. There’s nothing that you can’t stop. There is that much work coming through the door, [and] when you see that [staff] are at capacity, you take over to support them, but then you can’t do your job.” ORANGA TAMARIKI SITE LEADER

“At some point, you have no choice [but to take on a caseload].” ORANGA TAMARIKI SITE LEADER

We also heard that social workers were making decisions on whether to act not on individual circumstances and risk to the child but in comparison to other cases in front of them. This creates a threshold for action that is based on neither risk to the child alone nor the assessment tools but based on capacity.

In Bay of Plenty, we heard that issues highlighted in our 2024 review remained unresolved. We heard the Oranga Tamariki restructure, cuts to resources and what kaimahi told us was a hiring freeze have led to increased workloads for frontline social workers.

In one site we visited in another region, we heard that there are a significant number of unallocated cases. We heard examples of social workers at this site making critical decisions, only for cases to not be allocated and “go into the abyss”. There were concerns from social workers about this practice not “servicing ” well because it delays social workers engaging with whānau, and high caseloads make it difficult to provide adequate support or visit tamariki. More recently, we heard that a push to reduce the number of unallocated cases has led to unintended consequences. Rather than allocate cases, sites have simply closed unallocated reports of concern.

Accepting that not all reports of concern require a statutory response, we have not seen any evidence that Oranga Tamariki is any more likely to follow up a report of concern now than when we last reported. It continues to make decisions that are unduly influenced by the available resource. If anything, things may be worse than we found in 2024.

In our 2024 review, we noted Oranga Tamariki had made changes to its guidance on initial assessments. This included broadening who can be contacted during an initial assessment to determine whether a core assessment53 is required.

We noted that, rather than strengthening practice, this change may sometimes increase risk to and by placing greater weight on the views of some individuals – who may be the perpetrator or afraid of or protecting the perpetrator – rather than focusing on the safety of tamariki and rangatahi.

There was a lack of guidance for kaimahi about when – and how – to balance the views of with the safety needs of tamariki and rangatahi. Many community professionals shared concerns about the decision making of Oranga Tamariki social workers when the safety of tamariki and rangatahi is at risk. We heard from some community kaimahi that Oranga Tamariki social workers ask them what they should do. They felt that many Oranga Tamariki social workers lack confidence and understanding of their statutory role and responsibilities.

Some community kaimahi told us of times they have had serious concerns about the safety and risk of abuse to tamariki and rangatahi, considering decisions made by Oranga Tamariki kaimahi.

“I think a lot of social workers don’t see the actual danger to tamariki – I get you can’t remove kids willy-nilly as it impacts psychologically on tamariki, but at the same time, some social workers don’t appear to have the ability to identify high risk.” COMMUNITY AGENCY KAIMAHI

A couple of whānau members also shared examples of times they felt decisions from Oranga Tamariki social workers were not sufficiently focused on the safety and risk to their tamariki and rangatahi.

“[Oranga Tamariki] let me down. Baby was being neglected, which was what I said was going to happen if they took that route [of not applying for custody orders]. They said they were trying to give [the mother of the child] an opportunity to sort her shit out, but I was like our main concern was that baby was safe – wasn’t that their job?”

Some community professionals told us they felt Oranga Tamariki lacked strategic direction, transparency and consistent guidance to support its kaimahi. They questioned how much risk drives decision making, noting that sudden changes seemed to reflect resource availability and media attention rather than any clear rationale.

“We find some [Oranga Tamariki] decisions made are in a knee-jerk way. The whole plan changes and you’re [the] last to know. I think it’s practice that’s a means to an end and not trauma informed.” COMMUNITY AGENCY KAIMAHI

Oranga Tamariki site leaders and frontline kaimahi we met with in 2025 told us that the practice shift messaging tells them to follow a relational and holistic practice framework. We heard that there was a disconnect between how sites want to respond to tamariki and whānau – in relational ways – and the expectations from national and regional offices, which was more transactional.

“[Regional office] need to get on board with some of our relational ways of working because [not being on board] can be a barrier … [children] are waiting cos we can’t get internal processes in line. In the last three years, there’s been lots of training but that comes from the top. They’re not on the same page. We’re told this and that, but the thing is young people are still sitting in limbo not knowing what the next steps are. We see lots of anxiety for kids, young people not feeling safe and feeling unsettled. We are needing to get better at that.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

In addition, we heard concerns about the capability of some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi to make the right decisions. Some site leaders told us how the capability and skills of some social workers impacts their practice and that some social workers lack capability and confidence when undertaking assessments. This means assessments are not always carried out, and site leaders sometimes need to step in to support social workers to do them.

“We are multi-tasking here … We are switching between practice lead, social worker and supervisor. We are having to step in and do social work because our social workers don’t have the capability to make practice decisions.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

Tamariki aged under 5 are the most at risk but they are no more likely to be seen

Although data on child deaths in shows that tamariki under 5 are at higher risk, the response from Oranga Tamariki to reports of concern does not prioritise seeing these very young tamariki.

Data from the last nine years54 shows the proportion of reports of concern that resulted in further action – where Oranga Tamariki visited the tamariki for whom safety concerns were raised – was around 30 percent for tamariki of all ages up to 14.

Reports of concern about rangatahi aged 15 and older were less likely to result in further action responses from Oranga Tamariki at around 11 percent.

Induction and training are not adequately preparing social workers to assess risk

We asked Oranga Tamariki if it had made any changes to social worker induction and training since our last review and if it knew what impact those changes were having.

In response, Oranga Tamariki told us that the structure of its induction and training programme has been improved since our last review to create flexibility for social workers to meet their induction requirements. It told us there are now two or three opportunities for social workers to complete each module and attend face-to-face wānanga. Previously, the schedule was prescribed, so a missed event was difficult to catch up and caused delays in completion. Oranga Tamariki told us this new approach is helping social workers schedule their learning around work and other commitments.

However, what we heard from Oranga Tamariki kaimahi tells us a different story. Some Oranga Tamariki site leaders and kaimahi told us their compulsory training is a “one-size-fits-all” and “tick box” activity.

We heard that the training does not teach the specific skills needed for different roles, and cultural training is not specialised to the different needs of each community. In addition, we heard that new kaimahi do not receive training for a long time after they start, which delays them understanding and applying the legislation in their work.

We heard from some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi that there is not enough training and support for social workers, including a lack of induction training for new social workers. As an example, one kaimahi said that, while the practice centre is a useful resource, it can be difficult to use effectively as there is an overwhelming amount of information for newer kaimahi to “trawl” through.

“I think the organisation lacks training for new social workers. I have seen too many times where new social workers are just given things and told ‘here go, do it’ but then they get into trouble because they didn’t follow the right practices.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

We heard the organisation has a “sink or swim” mentality that affects staff retention.

A few kaimahi told us organisational expectations do not allow sufficient time for training, and valuable training becomes “a pressure” that is “overshadowed” by their workload.

Some Oranga Tamariki kaimahi told us there is a lack of support from leaders to implement training they have received on practice frameworks and legislation. We heard that some kaimahi put training into practice themselves without support from practice leads and supervisors. For example, a couple of kaimahi told us they had not received any training on Tiaki Oranga, the recently launched new assessment framework, and one kaimahi described feeling as though the training “has just been left behind”.

Our review this year suggests that the issues we identified in 2024 are persisting.

We have continued to hear that inconsistent messaging about the practice shift and how to apply it may be placing tamariki and rangatahi at greater risk. We again heard that training and induction is not meeting social workers’ needs, although it may be too soon to see the impacts of changes Oranga Tamariki has made. We will continue to look at this as part of our regular monitoring practice.

Health NZ also has a role. As highlighted in critical gap two, expertise from Health NZ professionals could assist Oranga Tamariki social workers to assess harm and the risk of harm. However, the capacity and capability of Health NZ to provide this support is currently limited.

We continue to hear concern from professionals in other agencies and about the high threshold for Oranga Tamariki to take action in response to their reports of concern.

“[The Oranga Tamariki] threshold seems to be climbing because of their inability to stay on top of things. I know that they can’t handle it all because of the amount of [reports of concern] that are coming through. When people fill that [report of concern], the expectation is that [Oranga Tamariki] will do something about it sooner rather than later.” POLICE KAIMAHI

“With the [child aged under 2] who was reported [with more than a dozen hospital admissions], however many [reports of concern], no intervention from Oranga Tamariki.” POLICE KAIMAHI

“There is a big gap in the antenatal space – we have a woman who is about to be released who is not allocated anyone [within Oranga Tamariki]. I advised Oranga Tamariki and they have done nothing about it. Oranga Tamariki social workers miss the opportunity to engage with pregnant women here before they are released. Women are more open to engaging here.” CORRECTIONS KAIMAHI

“If they are nearing [age] 17, they don’t really get any help. It doesn’t matter how many complaints we do.” HEALTH KAIMAHI

“How bad does it have to get, really?” HEALTH KAIMAHI

A couple of Police kaimahi told us they thought the threshold for response from Oranga Tamariki had risen, especially in cases relating to family harm. They felt there was sometimes a lack of action in response to , and involved in family harm.

“Exposure to family harm isn’t generally enough [for Oranga Tamariki to take action]. Family harm doesn’t meet the threshold. These kids are going to grow up, they would be saying ‘You were at my house every week and you didn’t do anything’, only because they didn’t meet the threshold.” POLICE KAIMAHI

Child death reviews echo the view that the threshold for action is too high

Concerns that the threshold for action is too high are reinforced by two Oranga Tamariki child death reviews that found health professionals had made reports of concern to Oranga Tamariki months before the deaths of the two tamariki.

The reports of concern noted that the significant injuries of the tamariki were inconsistent with the explanations given.

The death reviews show that Oranga Tamariki and Police responses to the reports of concern may not have adequately addressed the risk for these tamariki, especially considering the information from health professionals.

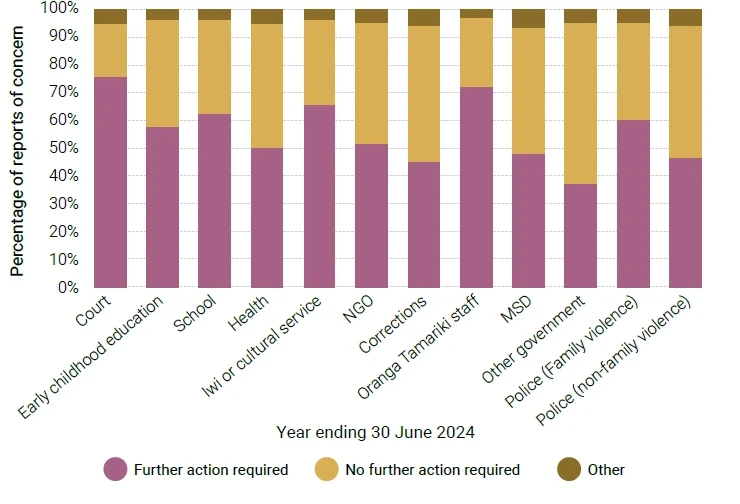

Action taken varies across different groups of professionals

Oranga Tamariki decisions to take further action on reports of concern vary across notifier types. For this review, we looked at reports of concern from 2023/24 to see what had changed since our 2024 review (Figure 5).

As our 2024 review identified, Oranga Tamariki decided to progress only 40–50 percent of reports of concern from professional notifiers. This indicates that the assessment of risk by professionals when making a report of concern does not always align with how Oranga Tamariki assesses its need to intervene.

Across all reports of concern, Oranga Tamariki made a decision to take further action for 51 percent (36,400) of reports of concern in 2022/23, 50 percent (37,100) in 2023/24 and 40 percent (42,400) in 2024/25.55 While the proportion of reports of concern where action is taken appears to be decreasing, the actual number of reports of concern that progress has remained consistent (around 40,000 are progressed each year).

What the data cannot tell us, however, is whether the threshold for intervention is getting higher, as was perceived by the professionals we heard from.

Figure 5: While there was variation across groups, a high proportion of reports of concern made by professionals continued to receive no further action by Oranga Tamariki.

Oranga Tamariki death reviews we looked at also identified that reports of concern are an opportunity for Oranga Tamariki to intervene to prevent harm, but this opportunity is not always taken.

“There was no consideration of the cumulative harm the children were experiencing. There were many [reports of concern] received that gave us the opportunity to look at the issues with fresh eyes however some of these were closed with no further action. The new concerns were also not considered in the context of the considerable history and intergenerational concerns.” ORANGA TAMARIKI CHILD DEATH REVIEW

We heard that Oranga Tamariki is continuing to refer and to community providers, but funding and contracting cuts mean many of them are under pressure and cannot deliver the services needed. The Oranga Tamariki kaimahi we met with were concerned about the impact of this.

“We’re encouraged to lean on the community, but all our community [providers] have had multiple contracts taken. We need them [community providers] but the powers that be decided ‘nah’.” ORANGA TAMARIKI KAIMAHI

Many community organisations told us that cuts in their contracts mean they are having to be “creative” to fund their work. Some are working without funding, some are working above and beyond their funding and others are facing cuts and scaling back their services. Months into the 2024/25 financial year, some were still unclear about proposed changes and timeframes and were working without funding.

“Our contract and funding expired on 30 June 2024. We have been currently running for two months without funding … We are told ‘yes’ to more funding but not when, so we have no timeframe. We have no one to contact at Oranga Tamariki any more … We are not a provider who had pūtea [money] to tie us over … We contact [Oranga Tamariki] every other day and there is no new information. The government tell us to fill the beds but haven’t given us funding.” MĀORI SERVICES KAIMAHI

We heard there is an expectation that services will continue to be provided even though funding has been reduced.

“I think if you give [Oranga Tamariki] an inch and they take a mile. They are very quick to ask us different things, pile on [work] outside of the contracts we are working.” COMMUNITY AGENCY LEADER

“Yeah contracts, there’s a lot less wiggle room. We will see a need and take a look into what we might be able to do but then it’s like, ‘oh no, we can’t with the funding we have’ … It’s just getting really tight or cut completely. How do you see the same number of clients if you only have this [gestures to a small amount]? We have waitlists as long as our arms.” COMMUNITY AGENCY LEADER

Oranga Tamariki kaimahi also told us the contract changes are impacting on their local relationships and having a negative impact.

“I do worry about our ability to sustain our social structure when so much of our ability is taken away from our community. We’re the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff and it is now on fire. We can’t go to the community because they don’t have the capacity any more.” ORANGA TAMARIKI LEADER

In October 2025, Oranga Tamariki announced it would extend contracts due to expire on 31 December 2025 through to March 2027. This gives community providers greater certainty to enable them to deliver services and supports to tamariki, and their whānau.

For Oranga Tamariki to respond appropriately to reports of concern that require a statutory response, a resourced and capable community sector that meets basic social needs is required.

Community agencies are able to engage with and help them access resources such as food and housing and supports such as for parenting, mental health and drug and alcohol addictions. In turn, this may help prevent harm and further reports of concern. In working with whānau, community agencies provide safety in that they have eyes on and can escalate serious concerns to Oranga Tamariki for a statutory response.

Te Reo Karanga, a community-led contact centre in Whakatāne, is an example of what is possible

Oranga Tamariki is trying to achieve this vision through its Enabling Communities approach, and one example of this is Te Pūkāea o te Waiora in Whakatāne – an initiative launched by Te Tohu o Te Ora o Ngāti Awa and Eastern Bay of Plenty Provider Alliance in 2024. It includes Te Reo Karanga, a -focused and community-led contact centre in Whakatāne.

Calls made to the Oranga Tamariki NCC that fall within the Whakatāne site catchment are redirected to Te Reo Karanga, which triages the calls and helps whānau to access community information and services. We heard the triage process and provision of support by Te Reo Karanga to tamariki, and their whānau is working well. Two agencies spoke positively about it, noting that reports of concern are responded to quickly and tamariki, rangatahi and whānau can access a range of services in the community to support their needs.

All reports of concern that go through Te Reo Karanga are referred to Oranga Tamariki for a statutory response or those that might normally receive a no further action response are allocated to whānau navigators. Whānau navigators assess the needs of whānau and provide the services needed or refer to other community agencies. This allows tamariki, rangatahi and whānau whose needs do not meet the threshold for statutory intervention by Oranga Tamariki to access support and have their needs addressed holistically.

“One of the things that we’re committed to is no case gets closed. There will be a visit. Every referral that we get through Te Reo Karanga, there will be a home visit to discuss what the concerns are and offer assistance. They can decline the service, but part of our assessment is, if there are risks still existing, we can go back into [Oranga Tamariki] and escalate it back to [Oranga Tamariki].” TE REO KARANGA KAIMAHI

Te Tohu o Te Ora o Ngāti Awa shared information and data with us that shows some promising early results. Alongside data from Oranga Tamariki, there are indications that early responses to whānau by the community can be an effective way to manage some reports of concern.

A local Oranga Tamariki leader told us that triage by Te Reo Karanga has been working well for reports of concern from Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service that do not meet the statutory threshold. They said an understanding has developed that “Oranga Tamariki don’t need to be the ones to do something first”.

Te Reo Karanga has enabled the local Oranga Tamariki site to focus its resource where it is most needed. Crucially, although Te Reo Karanga relieved the local Whakatāne site of the work of responding to reports of concern, Oranga Tamariki decided not to reduce the number of social workers at the site. This meant Oranga Tamariki could focus on carrying out its statutory role. However, more recently, we heard this could be at risk, with Oranga Tamariki social workers from the Whakatāne site being required to cover vacancies at other sites.

Te Reo Karanga is an example of what can be done. Not only does it provide a more comprehensive response to the needs that may underlie a report of concern, but it also addresses those needs early to prevent further notifications, reduce potential harm and limit increased involvement in the oranga tamariki system. Doing this well requires the right help and support, including from other government agencies, to be involved from the earliest stage and not only in the most serious cases.

Resourcing the broader system and communities to respond to needs that do not require statutory intervention would enable Oranga Tamariki to direct its focus to responding to reports of concern that do require a statutory response. Without this, it will continue to struggle to respond to the number of reports of concern it will inevitably receive and to ensure the tamariki at the centre of them are safe.

49 Oranga Tamariki. (2025, June 30). Understanding the increase in reports of concern. orangatamariki.govt.nz/about-us/research/our-research/understanding-the-increase-in-reports-of-concern/

50 Ombudsman. (2020, October 24). Failure by Oranga Tamariki to investigate reports of concern and complaints. ombudsman.parliament.nz/resources/failure-oranga-tamariki-investigate-reports-concern-and-complaints

51 Section 17(1)(c) states: “unless it is impracticable or undesirable to do so, as soon as practicable after a decision is made not to investigate or the investigation has concluded, inform the person who made the report—(i) whether the report has been investigated; and (ii) if so, whether any further action has been taken.”

52 See footnote 2

53 If an initial assessment determines further action is required, this subsequent phase of investigation into the report of concern is known as a core assessment.

54 This refers to data provided by Oranga Tamariki on reports of concern covering the period July 2016 to June 2025. This data was grouped annually and broken down into age bands for for whom reports were made.

55 Data was provided for Oranga Tamariki decisions on reports of concern for 2024/25 but we do not have this data broken down by notifier type for 2024/25.